The thought of turning my 16-year-old son Andrew loose on Southern California freeways, with barely six months' experience behind the wheel, struck terror into my heart — even though he wasn't the least bit intimidated himself. So when I had the opportunity to send him to a defensive driving school, taught by racing school instructors, I jumped at the chance.

The cool thing about the one-day class (and when you're dealing with teenagers it's important to be cool) is that the teachers at Danny McKeever's Fast Lane Racing School don't try the old adult trick of scaring the heck out of the kids. There are no Red Asphalt-style videos shown here, as there were in my son's state-approved driver's ed class. Instead, the instructors talk about the best ways for teenagers to avoid accidents by becoming better drivers and increasing their knowledge of vehicle dynamics.

While Danny McKeever stood in the second-floor classroom, covering basic principles of braking and cornering, high-performance cars blazed past on the straightaway of the Willow Springs Raceway outside. McKeever casually mentioned that most racecar drivers are defensive drivers on city streets because they don't have anything to prove. And, by the way, he added, why get into a road rage situation? "It's not a competition out there," he said. "You'll never see that guy again."

But that's about as far as the cautionary material went. Mostly, McKeever was interested in teaching young drivers the physics of how to guide a "3,000-pound projectile" safely around disaster. The principles of avoiding accidents are similar to those of driving a racecar at its limits. Therefore, the defensive driving classroom session was combined with a high-performance driving class. (Later, the two groups split up for hands-on driving exercises on the various Willow Springs tracks.)

McKeever, a former racer and veteran driving instructor, who preps celebrities for the Long Beach Grand Prix, had an easy-to-understand style of teaching. He illustrated concepts by turning a disembodied steering wheel taken from a sports car and drawing diagrams of the tires' "contact patches" on the blackboard. Contact patches are the portion of the tire that touches the road. Under most conditions they show whether the weight is distributed evenly. When braking the weight plunges forward onto the front tires; when accelerating it is thrown back onto the rear tires.

"You are all tire managers," McKeever said. "You have to know where the limits of the tires are. How far can you turn the wheel and still keep in control of the car?"

The class began with very basic information about how to sit in the vehicle and the best way to grip the steering wheel. Later, McKeever explained how a car's weight shifts in severe braking and steering maneuvers which change the contact patches — and thus the traction. Finally, the class moved outside for real-world experience on the Willow Springs track.

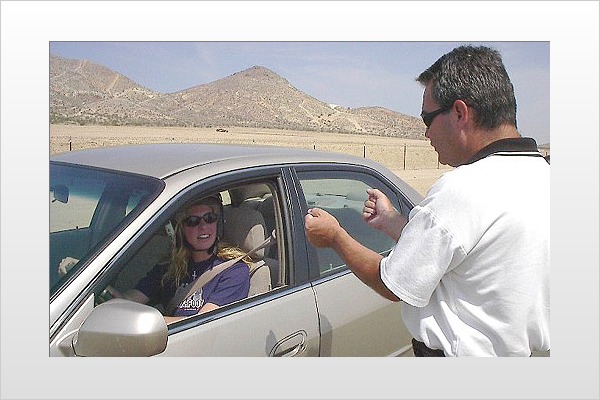

Teenagers enrolled in the $375-class performed the driving exercises in their own cars. This made sense since the benefit of the class is to better learn the handling characteristics — and the limits of — the car they most often drive.

The five teenagers in today's class drove their cars to an oval track where a course was marked by orange cones. Instructors Tom Hunter and Raul Moreno had the young drivers practice hitting the brakes, lifting off the brake pedal, steering around obstacles and then braking again. This simulated a situation in which a car has stopped in traffic and there is no time to come to a full stop. It showed drivers how a car becomes difficult or impossible to steer when the brakes are locked up.

"This is an avoidance maneuver," Moreno told 18-year-old Jackie Francois. "Full throttle to emergency stop — then avoidance. The car is going to want to sidestep on you, so be ready for that."

Hunter encouraged the teenagers to slowly increase their speed through the cones.

"They get two things out of this," said Hunter, watching the moving cars. "Vision is huge. They learn to drive so that they aren't just looking at the end of the hood. So when they are driving on the roads, they are looking at everything that is going on around them.

"The other thing they get out of this is they feel vehicle dynamics and what happens under an emergency situation. This is similar to when a kid runs out from between two parked cars and they have to react instantly."

Hunter, a high school football coach, continued, "They come here to understand why. Once they understand why, it's amazing what they can accomplish. That's why the young kids, when they're trained right, are so good behind the wheel."

Soon, the teenagers were circling a small oval track, braking, turning, braking again. The hot desert air was filled with the sound of revving engines and screeching brakes. Between laps, the students stood beside their cars, excitedly sharing their reactions.

Nearby, sitting in the shade, the parents watched the class, and talked about what had brought them here. Kate Simon said her daughter, Jean, 15, would soon be driving to school through a busy freeway corridor. "Her route to school is hair-raising," she said. "I want her to have a better overall understanding of what she is doing."

Robert Schulz, a former drag racer, said his son Travis, 17, a senior in high school had gotten interested in performance driving and recently modified his Honda Civic hatchback. "I hope he gets the racing bug because, once I started racing I was a lot safer on the street. You don't have to prove anything; [the track] is where you prove something."

The classroom session was rewarding, Robert said. "I learned a few things. And I've been around a long time messing with cars. It taught some good basic stuff you never think of."

After lunch there was another classroom session in which McKeever began to talk about how to control skidding. He told the teenagers they would be given time on the skid pad, an open asphalt area where cars can be driven without fear of hitting anything.

"On a skid pad, you can learn more about how a car behaves in 15 minutes than in two hours on a track," McKeever told the class.

A huge water truck wetted down the skid pad and then the students took turns practicing different maneuvers on the slick surface. They began by locking up their cars' brakes and trying to turn. Very quickly, they realized this doesn't work. You have to get off the brake pedal, or have a car equipped with antilock brakes to steer around danger.

Under the blazing desert sun, the skid pad dried quickly. But the truck wetted it down again and the students practiced the fine art of "steering into the skid." This is a phrase that so often leads to confusion when expressed as a theoretical concept. But with hands-on experience they soon realized what it meant.

The skid pad was the most popular part of the school. As Jean Simon put it, "It was fun. Scary, but fun. I've never skidded before. It was totally unexpected. All my friends have gotten into accidents and they don't know any of this."

During a break, I asked McKeever if insurance companies would give a discount to teenagers who took his class. He said he was looking into that, but he said that, in general, there are many contradictions in the insurance industry.

"For instance, I work with a lot of police departments, and most of the cities are self-insured," McKeever said. "They'll write a half-million liability check. But they get huffy when you want them to spend a few thousand bucks to train their officers." Furthermore, he pointed out that police officers frequently train with their guns. "But some of the officers have never been to driver training in 20 years. They use their car every day but in the life span of a police officer, they will use their gun zero to three times. Now what's wrong with this picture here?"

After the class ended, I drove home with Andrew, wondering if the young drivers learned something that might someday save their lives. Or had it just been a romp on a race track, spinning around in cars and calling it educational?

I put the question to Andrew: "Come on now. Honestly. What did you learn?"

"I knew before I came here that it's not good to brake when you're turning," Andrew said. "But this taught me why it's not good. Doing those exercises so many times you get used to not braking in the turns. If there is a car that stops in front of you, you will have an overall better feel for how to brake and avoid the accident."

Yes, it was the repetition that was important, the chance to feel what skidding is like before they are skidding for real, with cars all around them going 70 miles per hour. Then they could react without thinking. Reacting was the key. Thinking, under those circumstances, was useless.

But would the class save your son's or daughter's life? For $375 and a day in the sun, I'll take the chance that it could someday make all the difference.