For more information on the Honda FCX, click here.

Faith in the long-term future of the internal combustion engine is hard to come by at the headquarters of most automakers. Sure, for the immediate future we're all still going to be driving around in cars, trucks and SUVs powered by engines burning some sort of petroleum product. But over the horizon lies the fuel cell — a device that generates direct current (DC) electricity through electrochemical conversion without generating any pollution. Unless you've got tenure in MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, you probably can't build a working fuel cell at home, and even explaining how they work takes more space than is available here (though we gave it our best shot in BMW's Paradigm Shift), but GM, Ford, DaimlerChrysler, Hyundai, BMW, Toyota, Volkswagen, Nissan and Honda all see a fuel cell-powered future coming.

Now Honda has gone and let us drive its hydrogen fuel cell-powered FCX on actual Southern California roads and freeways. While that fact alone makes it seem as if the fuel cell revolution is imminent, every mile in the FCX makes the challenges ahead for the technology more obvious — and more daunting.

Honda makes about 400,000 Accords for sale in the U.S. every year, and the company will probably only make — by hand — a total of 40 FCXs over the next couple of years. But for a car that's being built in a quantity only 1/10,000th of that which Honda is capable, the FCX is well finished. Inside, the plastic parts all fit together properly and feature a fine texture, the carpeting is neatly trimmed and there's no sign of dangling electrical tape or spit wad engineering.

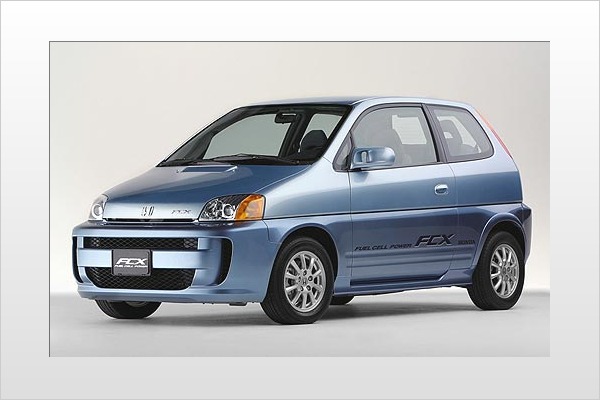

The exterior uses the same body panels as Honda's departed (and barely remembered) electric car — the EV-Plus — with the addition of a new grille and bumper area to feed air to the powertrain's radiators. Considering its awkward proportions, there's no way the FCX could ever be described as pretty, but it's somehow instantly recognizable as a Honda and, again, well crafted throughout.

Those exterior dimensions are pretty agonizingly awkward. At 164.0 inches in overall length (10.7 inches shorter than a Civic coupe), the FCX is a very short machine. But it's also tall and wide (2.6 inches wider and a lofty 9.7 inches taller than that same Civic) and rides on a relatively long 99.3-inch wheelbase. It looks like a metallic baby shoe sitting atop a roller skate — as worn by an elephant.

Dinky as the FCX looks, it weighs in at a hefty 3,713 pounds. That's a startling 1,309 pounds more than a Civic coupe and 405 pounds more than a base Chevy Impala. This is a densely packed automobile with heavy power and drivetrain equipment packed all along its length.

The front-drive FCX's heft starts under its nose where there's a large radiator in the center for the fuel cell system and another, smaller radiator for the DC electric motor that actually moves the car. Sitting behind the radiators and under a computerized power control unit, the motor feeds a two-stage reduction transmission (gearing isn't necessary with the consistent torque output of an electric engine). Then under the cockpit is a compartment packed with the Ballard fuel cell stack, a cooling pump, humidifier and system computer. The hydrogen fuel is stored (at 5,000 psi!) in two large tanks between the rear wheels. Each of those tanks consists of an aluminum bottle wrapped in carbon fiber and, finally, encased in fiberglass to both withstand the pressure inside it and resist the possibility of a puncture during a collision.

Finally Honda installs an "ultra-capacitor" just behind the rear seats that adds stored power to the fuel cell's output when it's needed. The ultra-capacitor scavenges power during braking and deceleration and effectively wipes out any of the three-door hatchback's cargo space. It's a neat piece of technology, but it would be nice to have some place to put the groceries.

Supporting all that heavy stuff is a strut suspension up front and a five-link independent system in the rear similar to the Accord's. The steering is by electric power-assisted rack-and-pinion setup, and the four-wheel disc brakes get their power assist from an electric vacuum pump and feature ABS and Electronic Brakeforce Distribution.

The FCX drives like the electric car that it is. An energy management display to the left and a hydrogen fuel gauge to the right frame the speedometer, but except for those two displays everything seems rather ordinary. Hit the accelerator and the FCX propels itself forward with some initial oomph — a product of the 201 pound-feet of instantly available torque. But ultimately, there's only 80 horsepower available, and this car weighs a lot, so acceleration falls off quickly. Passing at freeway speeds is a particularly nerve-racking experience in the FCX; there just isn't the reserve of thrust one hopes for when confronted with the slow-moving semi full of dairy products.

But it's nowhere near the frustrating experience of driving battery-powered electric cars. Because of their severely limited range, it's nearly impossible to drive a car like GM's EV-1 like a regular car and still be guaranteed there's enough charge left to get home. The FCX's range is about 170 miles, which is about half of what most gasoline-fueled vehicles offer, but at least double that of traditional battery-powered electrics. And, if there's a place to get hydrogen, refueling the FCX only takes a few minutes — while it can take eight hours to refill the batteries in an EV-1.

With so much of the FCX's weight down low, it feels stable and corners with dignity. But it's not a sports car; the steering is uncommunicative and there's not a lot of traction — this is not a car that wants to go out and frolic. But it does ride well and it's spooky quiet, with almost no engine noise and the underfloor powertrain components damping out road and tire noise.

Hydrogen is — by far — the most abundant element in the universe, but it's usually connected to something else, so it takes energy to strip the hydrogen from, say, the oxygen atoms in water. In order for the whole system to remain non-polluting, the energy used to "crack" off the hydrogen must itself be non-polluting. Honda's fueling station behind its R&D facility in Torrance, Calif., does that with solar-generated electricity. But that takes up acreage, and the Honda Hydrogen station covers maybe a third of an acre and generates just enough hydrogen to fuel one FCX once a day. Hydrogen is also tough to transport in bulk, has to be stored under pressure and is generally more difficult to work with than traditional fuels. Can all these challenges be overcome? Probably. But maybe not. And no one knows when the breakthroughs are coming, or from where.

Beyond that, fuel cells are still very expensive. It costs Honda about $2 million to build an FCX and right now it has delivered only one, to the City of Los Angeles, on a $500-per-month lease (with all fuel and service included). Obviously, that price would come down with mass production, but even a $100,000 small, non-luxurious, non-performance car with limited utility isn't going to attract many buyers. If Honda gets the price down to that of a car like the Prius or Civic Hybrid, and comes up with a more useful package, hydrogen fuel cell cars may indeed be ready to come into the world — and turn it upside down.