Archived Road Test

Archived Road Test

Originally published in Sports Cars Illustrated in April 1956.

So you can't climb Everest, you can't have Monroe, and you're not likely ever to ride a rocket to the moon. But you can, if you're properly heeled, achieve an experience that's in the same ultimate class—you can get yourself a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL. And if you really respond to machinery, the effect is the same.

After exhaustive road testing of a standard 300 SL, after driving impressions in a race-tuned version and interviews with several owners and specialist technicians, I'm ready to haul off and make a flat, unequivocal statement. This is the finest production sports car in the world. No exceptions, no qualifications. On all critical counts, it scores.

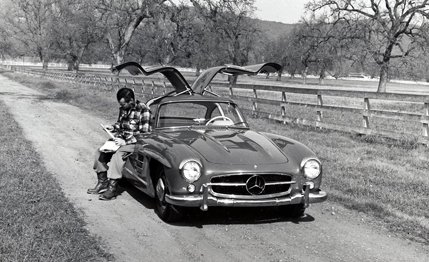

As a piece of automotive sculpture the 300 SL is a masterpiece. With its "gull wing" doors and its own Teutonic treatment of hippy, organic contours it stands splendidly apart from all the clichés of postwar styling, including the much-plagiarized Italian school. The 300 SL is a car that can take first place in a concours d'elegance, then clobber all comers in a tough race. Manifestations of its might are victories won all over Europe and the U.S. from the world's best all-out competition sports cars. At the same time it's a luxury carriage. Sports cars as a rule offer little in the way of comforts and nice refinements. In fact, starkness is part of the stock-in-trade of most sports car builders. But the 300 SL achieves the all-weather comfort and the rich finish of fine luxury cars without "engineering compromise"—that rarely-challenged excuse for typical sports car asceticism.

Beyond this, the 300 SL is prophecy incarnate. It's a pace-setter, a style-setter, a design conception that is bound to influence the world's automotive industry for many years to come. For example, a top Detroit stylist tells me that the 300 SL's roof doors are sure to be copied in the coming U.S. cars because they are the only means of getting in and out of the kind of ultra-low vehicles that the buying public craves. Several Detroit "idea cars" already have imitated this feature.

And styling is the least of the 300 SL's shock treatments to the industry. Gasoline fuel injection, first pioneered on the 300 SL, will give the internal combustion engine a new lease on life and probably delay the advent of gas turbines for years. Detroit, aware that FI means instantaneous throttle response, more horsepower and lower body lines, is already working all-out on injection. At the last count, there were 18 300 SL's in the possession of Detroit manufacturers who are boning up on FI's secrets.

Another feature that's bound to be copied is the position of the 300 SL's engine—mounted on its side to lower body lines and the center of gravity. The brakes are novel. While brake diameters in all cars have shrunk to conform to shrinking tire sizes, it took the designers of the 300 SL to think of widening the brakes to compensate for the lost friction area. The 300 SL has four-wheel independent suspension, a feature of M-B cars since the early thirties. This, too, is being readied on Detroit drawing boards. Even the intricate and expensive trapezoidal frame may be adapted to automation's techniques. Literally, the 300 SL is a car of the future that can be possessed today.

All 300 SL's are not necessarily alike. The standard package that you buy across the counter costs $7,463 at U.S. port of entry. It's a magnificent performer, with dazzling acceleration and a top speed of nearly 140 mph. But there are many performance options. It's beautifully, finely finished, but there are many finish options. The result is that although you can get a 300 SL for under $7500, few are sold for less than $8,000 after licence [sic] fees, taxes and options have been added. And if you want a 160 mph, all-out competition 300 SL you can invest $10,000 or $11,000 with no difficulty. But don't get the idea that the pin-money 300 SL is anything less than a going bomb.

The fire engine red, strictly standard model that I first drove came to my door equipped with meister mechaniker Robert Leutge, an expert technician sent to the U.S. by the Mercedes factory to train agency mechanics. He tossed the door up, slid over to the passenger's side, and I entered.

With the 300 SL this is something of an art and it varies according to build, sex and dress. For the first or fiftieth time it's a thrill. Actually, the car is not a handy package to climb in and out of but the mild gymnastics involved are a small price to pay for what you get. The somewhat limited entry area provided by the roof doors is dictated not by the car's lowness alone, but also by the extreme depth of the light, rigid, "three-dimensional" tubular frame. When you sit in the car your elbow rests on the door sill, which is wrapped over the top frame members. To simplify entry and exit for the driver, all 300 SL's are equipped with a steering wheel that can be folded under the steering column. Also, although the steering column is not adjustable, you can have your choice of two different column lengths.

Single OHC six-cylinder engine pumps 220–240 bhp out of 181 cubic inch capacity. Below 3600 rpm the engine is as docile as a flat-head Plymouth. Over that speed "all hell breaks loose."

Single OHC six-cylinder engine pumps 220–240 bhp out of 181 cubic inch capacity. Below 3600 rpm the engine is as docile as a flat-head Plymouth. Over that speed "all hell breaks loose."

The doors can be locked from the outside by the conventional method. To open them, you press a slightly-protruding cam which exposes the door-handle. Give this an easy outward and upward tug and the door floats up to its full-open position, aided by springs that give just the correct amount of counterbalance. The door must be slammed hard to be closed and this produces a loud, jarring thud. On the inside door handle of every new 300 SL is a somewhat disquieting notice urging that doors be locked from the inside to guard against their opening spontaneously at high speed.

When you're seated in a 300 SL you know you're in. You're practically encapsulated. You feel very much a part of the car, as you should be. Visibility is good. Straight ahead and just below eye level are a big tach and a big speedometer. There are plenty of other instruments and controls and they take some time to learn.

The first thing I noticed was the low mileage registered on the odometer—significantly below the 1,000-mile break-in period recommended by the factory. But Leutge put me at ease.

"You don't have to worry about winding up these engines," he said. "Before they're even dropped into a car they're run for 24 hours on a dynamometer, including six hours at peak output. Then they're torn down, checked, reassembled, and given another eight hours of running-in. Our times may be a shade slow, but don't be afraid to peak it in the gears."

The tricks of firing up a fuel-injection car are few and simple. For cold starts you pull out what corresponds to a choke and for hot starts you pull out a different button - that causes a whining, high-speed pump to go to work in the fuel tank. It not only purges vapor pockets from the fuel system when hot, but also makes available a two-gallon reserve fuel supply. The factory recommends that the extra pump be used continuously during high-speed operation.

This is not one of those engines the existence of which its makers have spent millions to hide. It explodes into urgent, buzzing life, idling at a busy but smooth 750 rpm and every fiber of the beast is ready to charge.

Author Griff Borgeson slide rules out some test figures. Note the seating position.

Author Griff Borgeson slide rules out some test figures. Note the seating position.

The 300 SL has positive syncromesh on all four of its forward speeds. You thrust it into first, simultaneously punch the throttle and release the clutch and, in a number of seconds only slightly greater than your reaction time, peak at 40 mph. The sensation of catapulting acceleration is unforgettable. Second, again with tremendous G's, propels the car up to the high sixties in scant seconds more. Third is a wonderfully useful ratio with terrific dig from about 9 to 96 mph.