Archived Comparison

Archived Comparison

The name Lancia is one of the oldest and most honored in the motoring world, and the firm's cars have always managed to combine solid practical virtues with a degree of individuality which is unusual in quantity-produced vehicles. The latest offerings from Torino's Via Vincenzo Lancia more than maintain this tradition, especially now that their power units have been enlarged to give more torque and greater flexibility.

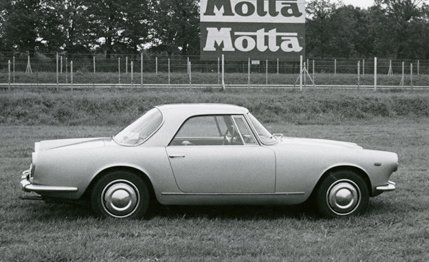

The cars featured in this combined test report are examples of Lancia's more sporting products. Although only one is designated "GT," both are Grand Touring cars in the proper sense of the word—that is, they are suitable for touring countryside and cities, not just race tracks. Both are also available in sedan and convertible form—and in each case the general mechanical layout in common to the whole range.

Ideally, both cars are two-seaters with lots of luggage space. Both have "occasional" rear seats—even more occasional on the Flaminia than on the Flavia—but in each case coupe styling and a short wheelbase render the rear compartment more suitable for children than full-grown adults; getting in and out of the back seats is another hazard in this connection, though the front seat backrests do fold down to permit such maneuvers.

In this, and in their degree of equipment—exemplified by things like red lights in the rear edge of the doors, which come on automatically when the doors are opened—the two cars have a lot in common. In basic design, however, they are poles apart, almost the only unifying feature being the use of four wheels. The V-6 Flaminia can be described as advanced conventional; to the customary expedient of front engine and rear drive it adds a de Dion axle, inboard discs, and clutch and gearbox in unit with the differential—all of which makes the weight distribution virtually 50/50. By contrast, the Flavia has a flat four engine mounted ahead of the driven front wheels, with the gearbox just behind them. Suspension in this case is by double wishbones and transverse spring at the front, with a beam axle on semi-elliptic springs at the rear. The only real criticism which can be made of this layout is that the engine and gearbox take up far more room than the British Motor Corporation's transverse-triplane arrangement.

The outstanding feature of the Flaminia is its ability to cruise effortlessly at 100 mph. David Phipps collected the car in Turin, drove straight out to the Autostrada, and let it find its own cruising speed. For about 50 kilometers his wife sat completely unconcerned, taking in the scenery with never a care in the world, but when he drew her attention to the speedometer, steady at 160 kmh, she started to look for seat belts. She need not have worried; the car ran "hands off" for over a kilometer and did not deviate an inch; Phipps tooted the horn gently at an indecisive Fiat, and a truck half a mile ahead pulled smartly in; and later, when a German-registered Mercedes veered out in front, he needed only to rest his foot on the brake pedal. Subsequently they got into a gigantic Milanese traffic jam, but the engine showed no sign of overheating or fouling plugs—probably because it is designed to run warm all the time. The car felt a little cumbersome (and more than a little vulnerable) under conditions like making U-turns, but at anything more than a crawl the steering is acceptably light, beautifully precise and completely free from kick-back. The shift is not the lightest in the world, but it is reasonably quick and seems absolutely fool-proof—which is more than can be said for some ultra-remote control mechanisms.

The seats are extremely comfortable, both in town and on the autostrada, and the combination of longer‑than-average fore-and-aft travel, finely adjustable back-rests and a telescopic steering column should make it possible for anyone to find a suitable driving position; this range of adjustments also helps the driver to offset the fatigue of a set position on a long run. Add to this an almost vertical steering wheel, and matching tach and speedometer, you have a car that makes you feel good every time you get into it. It also gives you a feeling that you do not need to rush or force your way through traffic to make your next appointment. It will get you there quickly—very quickly if necessary—but it will not encourage you to take risks or to throw it about. This is not to suggest that it doesn't handle well. Its Michelin X tires stay glued to the road whatever the weather, it goes just where it is pointed, and it stops time after time in a manner which Detroit can only dream about. But it is not a Sprite, and its very size and weight dictate a certain amount of caution.