Road Test

Road Test

Sometimes, when you probe too deeply into his Corvettes, Zora Arkus-Duntov goes opaque. It happens when you question an engineering change that perhaps required a measure of political finesse — and compromise — with the cost accountants. Or when you encounter some detail that he feels strongly about but is afraid the majority will misunderstand. Then Duntov pulls down the shade and becomes inscrutable.

"Zora, the rear window on the 1973 Coupe no longer is removable. Are the customers going to like that?" A thin, elusive smile. A slight shrug. "We know what is best for them." He says it lightly, as if it were a joke. It is not. He has reasons. Decisions on the Corvette are not made capriciously and he wouldn't want anybody to think they were. "At 140 mph, with the roof panels off and the side windows up, the air in the cockpit is still. The wind goes right over the top. Remove the rear window and you get a buffeting backdraft." So the rear window doesn't come out anymore. Some of the customers — those who would never bother to try it both ways — may be disappointed. That doesn't worry Duntov. He knows precisely what is good for them.

Which is the way it has been almost from the first. With the 1973 model the Corvette enters its third decade of production and now, as in the beginning in 1953, it is America's only sports car. Considering his present stature, it is surprising to find that Duntov was not a part of the original Corvette project. However, he was soon drawn into it and he is certainly the architect of its performance image that began to emerge with the 1956 models. Since then his influence has grown to the point where he is known worldwide as the Father of the Corvette, a position all the more remarkable in Detroit, the land of the committee car. So it follows, then, that if you are to understand the Corvette you must not only drive it with an open mind but also hear of it from Duntov.

It was about mid-summer, just when Detroit's new models were being shown to the press, that he called C/D's New York office. There was enthusiasm in his voice. He wanted us to know about his new Corvette. No, it wasn't to be the mid-engine car that was widely rumored for 1973 introduction, the Corvette Duntov has been measuring in his mind for at least 10 years. The bumper and safety laws have delayed that model. Instead, Duntov's new car would look much like last year's...but it would be improved. It would be quieter, much quieter, and would meet the bumper laws with only a small increase in weight. Nor would performance suffer to any great degree — to offset the power losses caused by tightened emission control requirements a cold air hood would be standard. Handling in normal traffic situations would be better too because of new radial ply tires and light-alloy wheels. Duntov was pleased. He reckoned that the new Corvette was the best ever and if we wanted to test one, or several, he would help in any way we asked.

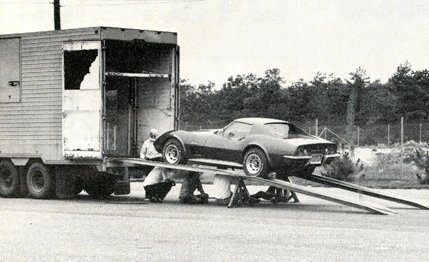

That was the beginning. In September, even before the new models were introduced to the public, a van containing four new Corvettes arrived at C/D's Long Island proving grounds, New York National Speedway. Along with them was Duntov. And even as the Corvettes were backing down the unloading ramp he began to point out differences between old models and the new. He started with the nose that can now live through a 5 mph punch into a barrier. The part you see is all body color, a flexible overlayer of molded urethane. Invisible behind the skin, doing much the same job as a stay hidden within a shirt collar, is a steel bumper bar attached to the frame by two ductile steel draw bolts. Collision energy is absorbed by the permanent deformation of the bar and by the extrusion of the two bolts through dies. The urethane, on the other hand, pops back out to its original shape. But the system is designed so that a 5 mph collision completely uses up the bumper bar and the two bolts. They then have to be replaced if you are to have protection for the next impact. Although it is obscure, this requirement is founded in logic. The system could have been self-restoring but such an arrangement is heavier...much heavier. Moreover, if that additional weight had been hung out well forward of the front wheels it would certainly have compromised handling. Which Duntov considers too great a price. We agree. So his new Corvette has a bumper that sticks out three inches farther than the old one, and it admittedly adds a certain amount of weight, but it doesn't ruin the car. And now the Corvette can live through a common parking lot tap on the nose without tearing up $500 worth of fiberglass. Considering the circumstances — Washington on one side and customers who expect uncompromised performance on the other — Duntov and his engineers had very little choice.