First Drive Review

First Drive Review

The Smart Fortwo electric drive is not going to be a geopolitical game changer. It’s not even going to change neighborhood energy policies. That’s because the initial run of this vehicle is limited to 1500 cars, only 250 of which are coming to the United States. Even when full-scale production begins in 2012, the volume will be a minuscule fraction of the few-dozen-million or so cars sold each year. But the electric Smart does give us a look at one approach to the electrification of the automobile.

As a diminutive city car (more than three feet shorter than the Mini Cooper), the Fortwo makes sense as a candidate for electric conversion. Why worry about range in a car that isn’t made for road trips in the first place? If it weren’t for the green wheels, mirror caps, and safety cage, the swap from petrol to electrons would be invisible from the outside. The electric motor, the single-speed transmission, and the Tesla-developed battery pack all sit below the rear cargo compartment in the space the 1.0-liter inline-three used to inhabit. Peak output of 40 hp is available in brief spurts; otherwise, there are 27 ponies on tap. Torque is quoted at 88.5 lb-ft, and yeah, that extra half lb-ft is probably worth mentioning.

Smart claims a 0-to-37-mph (60 km/h) time of 6.5 seconds, the same as for the gas version. Top speed is limited to 62 mph, and range is projected to be 84 miles from the 16.5-kWh battery pack. The whole system adds 308 pounds to the Fortwo, for a total of about 2150. Charging occurs through a 3.3-kW onboard charger and the recently adopted SAE J1772 standardized charging socket. With a 220-volt connection, the battery can fully charge in fewer than eight hours.

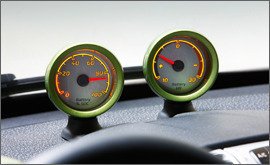

Inside, the Fortwo ED (Cialis jokes expected) is identical to other Fortwos. The two pods in the center of the dash—formerly, a tachometer and a clock—are now a battery meter and an ammeter that shows how much energy is being used or recuperated. The former fuel gauge in the center cluster shows battery level as well.

End Transmission

Starting up the electric Fortwo is a nonevent. You turn the key, hear some electronic clicking, and the gauges come to life. But once you start rolling, it’s immediately apparent that the electric version is superior to the gas version for one reason: no shifting.

Our biggest gripe about the gas-powered car is its accursed five-speed automated manual. Slow and choppy in operation, the standard Smart’s transmission forces you to lift the gas as soon as a shift initiates or brace yourself for a back-and-forth bucking as a higher gear engages. The electric Fortwo has none of that fuss. It just goes, the whine of the motor slowly increasing in pitch as you pick up speed. But this is no Tesla roadster. The Fortwo ED keeps up in Brooklyn traffic, but even the gentlest of taxi drivers accelerates at least 50 percent faster.

The rest of the driving experience is much like that of a normal car, or at least like a normal Fortwo. The first reason is that the gas pedal (yup, we’re still going to call it the gas pedal) works in typical fashion: Take your foot off, and the Fortwo ED coasts with minimal drag. It won’t creep forward without your pressing the pedal, and it even rolls backward on mild inclines.

The brakes, too, feel like old-fashioned hydraulics. This is because they are old-fashioned hydraulics, identical to those of the gas Fortwo. The only difference is that the first half-inch or so of pedal travel activates a higher level of regeneration in the electric motor to slow the car. Push the pedal farther, and you engage the hydraulic brakes. Although that progression is typical of hybrids, the Smart is different in that, once the pedal passes through the regen zone, the pedal is still applying pressure to the master cylinder. Typical hybrid brake pedals suffer cloudy feel because the pedal actuates just a potentiometer, which then tells a secondary system how much pressure to exert on the braking system.

Other peculiarities of the Smart remain unchanged in its electric form. The short wheelbase—73.5 inches—means the Fortwo gets tossed around by sequences of large bumps. Cargo space—12 cubic feet if you load it up to the ceiling—is small. And compared with other economy cars, the gas Fortwo costs as much or more than those that get nearly the same fuel economy with better performance.

That Smarts

If you haven’t already guessed, the Fortwo ED will cost much more. If you or your company (Smart expects 80 percent of EDs will go to corporate buyers) is among the lucky few to be issued a car, you’ll have to shell out $599 a month for the 48-month lease term. That works out to $28,752 and a car you have to give back after four years. The convertible version is a no-charge option.

The cost is offset by tax credits from the federal government, currently up to $7500 for electric vehicles. Based on the size of the Fortwo’s battery pack, it should get the full amount. On top of that, a company called Coulomb Technology (www.coulombtech.com) is offering free home charging stations as part of a federal grant. Not coincidentally, most of the regions where the Fortwo ED is being launched—Portland, Oregon; San Jose; Orlando; Indianapolis; and the I-95 corridor (Washington, D.C., to Boston)—are eligible for the free charging stations. Fortwo distribution in Detroit, Austin, and Los Angeles will occur shortly after launch.

We’ve been told that the exploratory, initial-run Fortwo electrics will be sold on a first-come, first-served basis, which means the line probably is already full. But the production model, promised to arrive in early 2012 as a 2013 model, will be available in every Smart store, for lease and purchase. Smart won’t even hint at the sticker price, but we’re guessing it will be expensive and highly influenced by what Nissan will charge (no pun intended) for the Leaf when it goes on sale early next year. The full-production Smart Fortwo ED will come with a new battery pack promising greater range and a higher top speed—two inevitable benefits of continued battery development.

Price aside, the Fortwo ED gives a good picture of the near-term future for electric cars. It will probably be used as a second car or for people in urban areas who want to take advantage of specific incentives (electric cars are exempt from London’s £8-a-day congestion charge, for instance) or the Fortwo’s size. In other words, it will be a lot like the uses for the gasoline Fortwo, but without the horrible transmission.