The decision-making process when selecting a camshaft used to be little more than answering the question, “How big do you want to go?” At one time, virtually all Detroit engines came from the factory with hydraulic flat tappet cams, and most of the time that was what went back in when building an engine for street performance. Solid flat tappet cams were OEM on some muscle engines, but were generally few and far between, while solid rollers were reserved almost exclusively for serious drag racing machines. Hydraulic roller cams came on the scene in the 1980s, offering yet another popular cam configuration. Today, we see street engines built with all four of these types of cams, and each have their pros and cons. The first decision that needs to be made when selecting a cam is just what kind of cam it is going to be. Here we look at these four cam configurations, their attributes, and which one is appropriate for a given application.

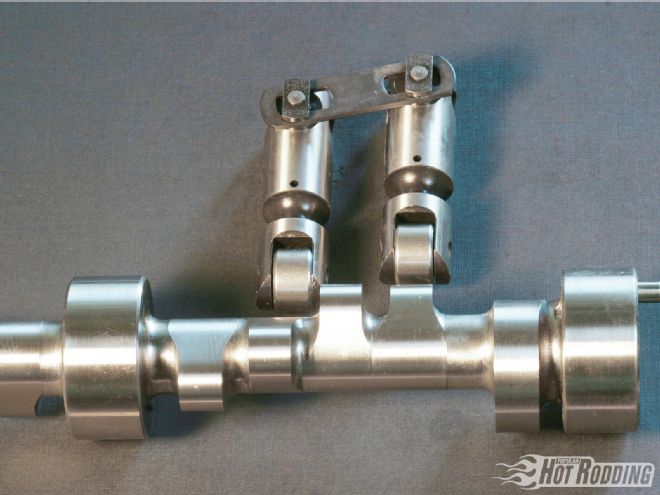

Cam and lifter kits are designed in both solid and hydraulic configurations. The hydraulic uses an internal mechanism to constantly adjust the valvetrain to zero lash, while the solid is manually set to the desired lash via an adjustable valvetrain. Given the same lift and duration at the valves, the power will be identical until the hydraulic begins to deliver false motion at the valves, typically a product of loss of valvetrain control at higher rpm.

Cam and lifter kits are designed in both solid and hydraulic configurations. The hydraulic uses an internal mechanism to constantly adjust the valvetrain to zero lash, while the solid is manually set to the desired lash via an adjustable valvetrain. Given the same lift and duration at the valves, the power will be identical until the hydraulic begins to deliver false motion at the valves, typically a product of loss of valvetrain control at higher rpm.

Hydraulic Flat Tappet

Even though the OEMs abandoned flat tappet hydraulic cams decades ago, it remains the largest segment of the aftermarket cam industry. The hydraulic mechanism provides a means of self-adjustment to the valvetrain, essentially eliminating maintenance in service, and does away with the need for precise valvetrain adjustment. The hydraulic plunger in the lifter body automatically zeroes-out the clearance in the valvetrain, soaking up production tolerances in the engine assembly in the process. The system works so well that most OEM engines are equipped with simple, non-adjustable, valvetrains. The travel of the lifter’s internal plunger provides a wide target for tolerance, and as long as the components are bolted together in that range of travel, a functional, quiet, and reliable valvetrain is the result.

All-out racing performance was never on the agenda when hydraulic lifters were conceived. The very hydraulic mechanism that defines the system can create a source of instability in the valvetrain, putting a cap on rpm and power. This condition will always manifest at higher rpm, potentially curbing the power curve prematurely, representing one of the key shortcomings of hydraulic flat tappet cams. These instability problems can be minimized by careful selection of the rest of the valvetrain components and springs. You will work harder as the targeted rpm range increases, but satisfactory performance is not difficult to achieve in applications under 6,000 rpm. Flat tappets are inherently limited in spring load capacity, with the point of failure being where the lifter meets the lobe, again putting a limit on this type of cam’s ultimate performance potential. In the rpm and lift range of the typical street performance engine, these shortcomings may not present themselves as an issue, making the hydraulic flat tappet a good inexpensive choice for a moderate street application.

The second major variation in cam types is whether it is a flat tappet or roller follower. The roller can tolerate much more load where it meets the cam. This allows higher spring loads to control more radical lobe profiles and higher lift, potentially increasing power in hotter engine combinations. Nevertheless, rollers are much more expensive than their flat tappet brethren, especially in retrofit applications.

The second major variation in cam types is whether it is a flat tappet or roller follower. The roller can tolerate much more load where it meets the cam. This allows higher spring loads to control more radical lobe profiles and higher lift, potentially increasing power in hotter engine combinations. Nevertheless, rollers are much more expensive than their flat tappet brethren, especially in retrofit applications.

Solid Flat Tappet

These springs with over 500 pounds open load would quickly destroy most flat tappet cams, but a roller will handle the load with excellent longevity on the street. Spring load capacity is a critical limiting factor with a flat tappet. Steps such as EDM direct lifter oiling and nitride hardening of the cam will improve the situation. In lower rpm, lower lift applications with moderate spring loads on a flat tappet will provide excellent power output, service, and durability.

These springs with over 500 pounds open load would quickly destroy most flat tappet cams, but a roller will handle the load with excellent longevity on the street. Spring load capacity is a critical limiting factor with a flat tappet. Steps such as EDM direct lifter oiling and nitride hardening of the cam will improve the situation. In lower rpm, lower lift applications with moderate spring loads on a flat tappet will provide excellent power output, service, and durability.

A solid flat tappet differs from a hydraulic in that there is no internal adjustment mechanism. Clearance for operation, known as “lash,” is set at the valvetrain, allowing the valvetrain to fully unload while the cam is off its lift cycle. A solid flat tappet is the simplest type of lifter arrangement, and this simplicity is the solid flat tappet cam’s greatest asset. It leaves very little to go wrong or cause rpm-limiting instability in the valvetrain.

In terms of rpm and power potential, the solid flat tappet works very well, and cost for the cam and lifters is comparable to a hydraulic flat tappet, though providing for lash requires an adjustable valvetrain, which adds to the cost in many applications. Periodic valve lash maintenance is required, however this aspect is often overstated. A solid flat tappet cam will generate more valvetrain noise than a hydraulic, but for many performance enthusiasts the solid’s mechanical music is considered a plus.

Since the solid’s main benefit is stability at high rpm, this type of a cam is best used where a high-rpm engine is the goal. As a flat tappet, the limitations on spring load capacity are similar to the hydraulic flat, which is rather contrary to the goal of maximizing rpm. Spring selection and valvetrain setup is critical when trying to make the most of a flat tappet solid. If the displacement, cylinder heads, induction, and rotating assembly are capable of supporting the engine into the 7,000-plus rpm range, a solid is a viable option. On the other hand, if the engine combination is destined to run out of rpm capacity and airflow at 5,500 rpm, a solid will be of negligible benefit versus a hydraulic.

Hydraulic rollers eliminate the need for cam break-in and the potential for lobe/lifter failure. This is a serious consideration when using high-rate-of-lift lobes and substantial valvespring loads, especially with modern oil formulations compromising lubrication with a flat tappet. Inside, a hydraulic roller uses exactly the same adjusting mechanism as a hydraulic flat tappet.

Hydraulic rollers eliminate the need for cam break-in and the potential for lobe/lifter failure. This is a serious consideration when using high-rate-of-lift lobes and substantial valvespring loads, especially with modern oil formulations compromising lubrication with a flat tappet. Inside, a hydraulic roller uses exactly the same adjusting mechanism as a hydraulic flat tappet.

Hydraulic Roller

The hydraulic roller has taken over as the most common OEM cam configuration, using an internal adjustment mechanism and a roller follower. It shares the hydraulic flat’s characteristics of quiet operation, no maintenance, and compatibility with a low-cost, non-adjustable valvetrain.

The primary benefit of this arrangement is a higher load bearing capability at the lobe/lifter interface. Flat tappet cams are subject to failure here, with disastrous results. The roller follower’s higher load capacity virtually eliminates these failures, and that is reason enough for many builders to favor this cam configuration. A hydraulic roller allows substantially higher spring loads than are practical with a flat tappet, lending to higher lift while maintaining valvetrain control. The geometry of a roller follower and cam lobe allows higher velocity than a flat tappet, so the lift curve can be designed with longer duration in the upper lift ranges, enhancing power production.

Side by side, a roller cam’s lobes (left) seem much brawnier and beefier than those of a flat tappet. This shape is by no means an indication of the difference in delivered cam specifications, but rather is dictated by the geometry of the respective lifter’s contact with the lobe. The best way to compare cam specs is to look at the duration throughout the lift range. Generally, a roller can achieve a higher velocity than a flat tappet, for more duration and quicker valve opening at high lift.

Side by side, a roller cam’s lobes (left) seem much brawnier and beefier than those of a flat tappet. This shape is by no means an indication of the difference in delivered cam specifications, but rather is dictated by the geometry of the respective lifter’s contact with the lobe. The best way to compare cam specs is to look at the duration throughout the lift range. Generally, a roller can achieve a higher velocity than a flat tappet, for more duration and quicker valve opening at high lift.

High-rpm stability and related drawbacks of the hydraulic roller are similar to those of a hydraulic flat tappet. The heavier lifter weight can make this more acute, however, some higher valvespring load capacity helps here. For extended rpm capability, aftermarket manufacturers offer limited-travel hydraulic roller lifters for popular applications, which restrict the lifter’s internal plunger travel to improve stability. With all of the hydraulic roller’s advantages it is an excellent choice for street performance, though cost scales up quickly in retrofit applications.

Solid Roller

Solid roller cams come into their own at the extremes of engine rpm, lift, and valvespring load—all factors that go hand in hand with a max-power engine effort. All of these factors, however, will compromise longevity. Manufacturers are producing solid-roller lifters with improved oiling to enhance street durability, but unless the engine combination and rpm requirements call for it, a hydraulic roller or even a flat tappet cam may be a better alternative.

Solid roller cams come into their own at the extremes of engine rpm, lift, and valvespring load—all factors that go hand in hand with a max-power engine effort. All of these factors, however, will compromise longevity. Manufacturers are producing solid-roller lifters with improved oiling to enhance street durability, but unless the engine combination and rpm requirements call for it, a hydraulic roller or even a flat tappet cam may be a better alternative.

In an automotive performance application, the solid roller combines the load bearing capacity of a roller follower with the inherent stability of a solid lifter body. The result is the ability to run very aggressive, high-lift lobes and the substantial spring loads necessary for high-rpm control. For all-out power production and rpm capacity, the solid roller is the king, however, in the wrong application, a solid roller is a poor choice.

A solid roller comes with bragging rights, but experience has shown that this cam configuration offers questionable long-term durability in a true street application. The most common failure point is at the follower wheel’s needle bearings, and when they let go, serious engine damage typically follows. New, higher quality lifters with improved materials and direct oil feed to the bearings are the industry’s answer. Before taking the plunge into a solid roller, the first question you should ask yourself is whether the engine truly needs one. If very high rpm, extreme valve lift, and the requisite high spring loads are all part of the plan, a solid roller is the right choice. If not, other cam options may meet your performance needs, generally with greater durability and at a much lower cost.