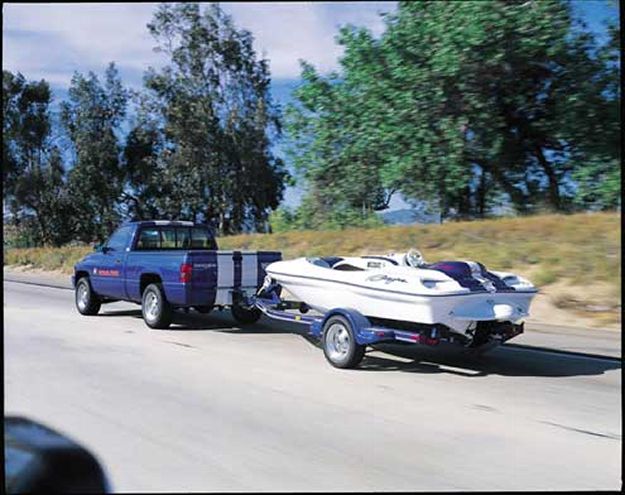

Although styling and performance will always be fundamental parts of a sport truck, the greatest appeal for many enthusiasts is the basic practicality of a truck. The vast majority of custom trucks are driven daily, and many are regularly expected to perform some kind of towing duty. With this kind of "real truck," it's important for you to understand basic towing principles and limitations.

It's one thing to cruise around in a cool-looking truck, but things can get complicated when you hook a load to the back of your pride and joy. First of all, the most fundamental considerations are the towing and trailering regulations required by your state vehicle code. The best place to check out state regs is the state highway patrol. If you stop by one of the stations, you might be given a booklet that details the rules and limitations relating to trailer or vehicle towing.

During this process you'll become aware of the many terms and expressions that are unique to working trucks and towing. Terms like gross vehicle weight, cargo weight, and gross axle weight can be confusing, and at times they may even seem to be conflicting. The most important thing is to be certain that you understand the ratings that apply to your specific truck and trailer combination. For instance, it's easy to confuse hitch ratings with vehicle tow ratings. It's not uncommon for a truck to be fit with a hitch that's rated well beyond the actual towing capacity of the truck. Of course, it's important that the hitch rating be sufficient for the load, but the safe towing limit is determined by the vehicle tow rating, not the hitch rating.

Important limitations: Gross axle weight ratings, gross vehicle rating, and so forth are usually listed in the owner's manual. In most cases, they're also posted on a tag that's attached to the latch-edge of the driver-side door or inside the door frame (usually on the latch pillar). Most midsize and fullsize trucks can pull loads up to approximately 2,000 pounds with relative safety. This weight point is a generalization, however, and it's important to realize that as the weight of the trailer load increases, two factors--gross trailer weight (GTW) and tongue weight--become increasingly crucial to safe vehicle handling.

Gross trailer weight is directly related to the towing capacity of the tow vehicle. The vehicle must be able to adequately accelerate, merge with traffic, climb typical road grades, handle reasonably well, and stop safely while pulling the weight of the trailer. Manufacturers determine the safe towing capacity through testing. If the towing capacity isn't published in the manufacturer's specifications, you can subtract the gross vehicle weight (as measured on a scale) from the gross combination weight rating, and the result will be the towing capacity.

Most trucks will pull loads beyond the manufacturer's tow rating, and if the engine has been modified to increase torque output, a truck may be able to move loads that are substantially beyond the safe capabilities of the suspension and brake components. The only way to ensure safety, especially if you're going to be towing a relatively heavy trailer rig, is to verify the weight of the trailer and compare it to the towing capacity of the truck.

Trailer manufacturers also provide weight specifications for their products. The most important ratings are the gross trailer rating and the useful load. In the case of a hauling trailer, the gross rating equals the empty weight of the trailer plus the useful load. For example, the empty weight of a trailer may be 1,500 pounds and it may be rated to a gross weight of 5,000 pounds. This means the useful load capacity is 3,500 pounds. When this trailer is loaded to the full useful load limit of 3,500 pounds, a truck with a towing capacity of 5,000 pounds or greater will be required to pull it safely.

Trailer loading is, however, a tricky business. It's surprisingly easy to load a trailer beyond its gross rating. Just like most trucks, the typical trailer will usually carry a load that's beyond the rated capacity. In certain circumstances this overloading can exceed both the trailer capacity and the truck towing capacity. It's easy to overlook load ratings or ignore actual loaded weights, but it's unwise. If you estimate that a load is near either the trailer or truck capacity, it would be wise to locate a vehicle scale to verify the actual weight (free standing). If you can't determine the actual weight, the safest approach is to lighten the load until you're certain the actual weight is less than the gross weight rating of the trailer and towing capacity of your truck.

In the case of a recreational trailer or a boat and trailer combination, the actual weight of the total rig can be deceiving. Even though the manufacturer provides a factory weight specification, this weight may not include options or modifications. And you must consider that the average recreational trailer acquires a lot of miscellaneous personal gear before it hits the highway. Similarly, the actual weight of a boat and trailer rig must include add-ons, miscellaneous gear, and the weight of onboard fuel.

The second weight factor to consider is trailer tongue weight. The weight of the loaded trailer is distributed between the axle (or axles) and the tongue. Most of the weight is carried by the axle, but as the cargo (or a portion of the cargo) is moved forward on the trailer, weight (downward force) is shifted from the axle to the tongue. In the same way, it's possible to shift the cargo rearward and reduce the weight on the tongue. For the tow vehicle to exert adequate control over the trailer, however, there must be some weight on the tongue. The recommended tongue weight for most trailers is about 10 to 15 percent of the gross trailer weight.

When a trailer is attached to a truck, the tongue weight is transferred across to the hitch and the rear of the vehicle. This additional loading behind the rear axle has two primary effects: First, It increases the downward force on the rear suspension and rear axle; Second, The additional weight behind the rear axle pivots across the rear axle, sort of like a teetertotter, reducing the weight bearing on the front suspension and axle (spindles). If the gross trailer weight and the tongue weight are kept within the rated limits, the truck will handle these effects. In extreme cases, however, overloading the rear of a truck may significantly reduce the steering response. These effects can be counteracted, within limits, by modern hitch technology.

When the gross trailer weight exceeds 1,000 pounds, most truck manufacturers recommend that the trailer be fit with its own brake system. Many states require auxiliary brakes when the gross trailer weight exceeds 3,000 pounds. Trailer manufacturers generally offer these systems as standard equipment or options.

There are two basic type of trailer brake systems: electric or hydraulic. Electric systems are activated by an electronic controller that monitors the brake system of the tow vehicle. Hydraulic systems can divided into three subcategories: surge, slave, or vacuum systems.

Surge-actuated systems are activated by a separate master cylinder at the trailer tongue. When the tow vehicle slows down, rearward pressure is passed through the trailer tongue to the auxiliary master cylinder on the trailer, which in turn, applies the trailer brakes.

Slave hydraulic systems are connected directly to the brake system of the tow vehicle and work in conjunction with the main system.

Vacuum systems are controlled by an auxiliary vacuum module connected to the vacuum booster of the tow vehicle. These systems are the most expensive and are most often used on very large towing rigs.

Electric and surge systems are the most common, and they're always a worthwhile if not mandatory investment. Slave hydraulic systems should be considered with caution. Most truck manufacturers don't recommend these systems. If there's insufficient capacity in the master cylinder or if any component in the system should fail, the brakes on both the trailer and tow vehicle could be compromised.

Trailer hitches are divided into two general categories: weight-carrying hitches or weight-distributing hitches. Weight-carrying hitches are commonly used with lighter trailers (3,500 pounds GTW or less). With this type of hitch, the entire tongue weight is directly supported by the hitch. As described above, the tongue weight is carried like virtually any other load placed in the bed of the truck.

For heavier trailers, a better choice is a weight-distributing hitch. This technology uses a pair of spring bars slung between the hitch and the trailer frame to form a flexing truss across the interface. In effect, the frame of the trailer and the frame of the truck are bound directly to each other, but the spring bars bend in the vertical plane, allowing the two frames to articulate separately. This flexible truss distributes the tongue weight along the length of the two frames. For example, if the tongue weight of a trailer is 600 pounds, when the trailer is hooked to a truck with a weight-distributing hitch, 200 pounds (approximately) of the weight will transfer to the front wheels of the truck, 200 pounds will transfer to the rear wheels of the truck, and 200 pounds will transfer back to the wheels of the trailer.

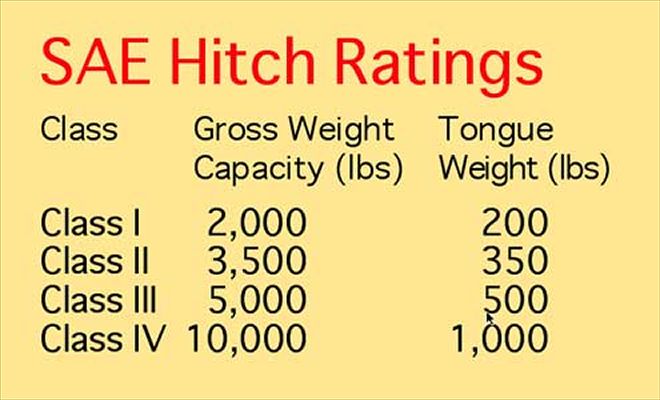

Hitches are also subclassified according to the gross trailer weight they can support. The class limitations established by the Society of Automotive Engineers are listed in the accompanying chart. In general, Class I hitches are suitable for light-hauling trailers, lightweight recreational, or fishing boat rigs and motorcycle/watercraft trailers. Class II hitches are suitable for medium-hauling trailers, small recreational trailers, and ski boat or light day cruiser rigs. Class III and IV hitches are for heavy-duty loads (see chart above).

The most important thing to remember here is that the maximum towing capacity of the vehicle is always determined by the lowest-rated element in the chain of hitch components. This chain consists of the trailer rating, the ball hitch rating, the hitch rating, and the towing capacity of the vehicle. The weakest, or lowest-rated, element in this chain always determines the maximum safe towing capability of the entire chain.

Quality aftermarket hitches are available from Putnam, Draw-Tite, Eaz-Lift, Reese, and others. These sources specialize in hitches that can be bolted directly to the rear framework of most popular trucks. As you'd expect, these designs must work around obstructions like the fuel tank, spare tire, and bumper mounts. In addition, most of these designs rely on stock holes punched or drilled in the frame by the vehicle manufacturer as convenient points to attach the hitch.

Some companies offer hitches that are welded directly to the rear framework of the truck. These designs must also work around factory obstructions. They aren't, however, dependent upon factory-located holes to attach to the framework. Often, this allows for fewer design compromises. On the other hand, expert welding--often within very tight spaces--is essential to ensure a top-quality installation. This isn't a do-it-yourself proposition, but it may be the best option when a heavy-duty hitch (Class IV) is required or when the rear frame or bodywork has been extensively modified.

Specialty companies, like HitchMasters in Van Nuys, California, can supply weld-on hitches for nearly any truck or custom requirement. Although these hitches are a little more expensive, they can provide the finest quality, and, within reason, they can be built to accommodate nearly any stock, specialty, or custom bumper or custom panel arrangement.

Ball Mount And Hitch Ball

Some weight-carrying hitches are available with removable draw bars. The drawbar is the hitch element that supports the ball. On a removable design, the drawbar is attached to a quick-connect mount built into the hitch. The drawbar mount is called a receiver, and these designs are generally known as receiver hitches. Removable draw bars are popular, obviously, because the hitch (with the drawbar removed) can be readily concealed behind a custom panel or rear roll pan. They also provide some small technical advantages. When the trailer is hooked to the hitch, the frame of the trailer should be roughly level. If the truck has been lowered, a standard hitch may lower the front of the trailer. An offset drawbar can raise the ball location, to bring the trailer back to a level stance. In addition, a removable drawbar design permits separate draw bars, with different size hitch balls, to be attached quickly and easily to the hitch.

The hitch ball diameter must match the inside diameter of the trailer coupler. Balls are available in three standard diameters. A 1-7/8-inch coupler and ball combination is common on small utility and boat trailers. The 2-inch-diameter ball is by far the most common and is generally used with couplers on trailers rated between 2,000 and 5,000 pounds GTW. A 2-5/16-inch ball is usually required for heavier trailers. A specific maximum weight rating is generally stamped into the top of the ball. For safe towing, this rating must meet or exceed the actual gross trailer weight.

In theory, modifications to the engine and brakes will alter the towing capacity of the vehicle. In practice, however, it's virtually impossible to measure the effect of these changes. Consequently, any modification should be viewed in an optimistically neutral manner. In other words, even though an engine or brake modification may potentially increase towing performance, the basic towing rating established by the manufacturer must still be observed.

Suspension modifications are another story altogether. Certain suspension mods can hinder the towing capabilities of a truck. The most common sport truck modification, lowering the suspension, reduces the static clearance between the rear framerails and axlehousing. Under light loading this may not be a problem, but if the trailer load is heavy enough to cause the frame to contact the axlehousing, the resulting damage can be severe. Adjustable airbags or air shocks may effectively raise the rear of the truck, increasing support for the trailer load, but a better solution is a weight-distributing hitch that would apportion some of the tongue weight to the other axles.

If the rear framerails have been cut to gain clearance above the axles, the towing capacity of the truck must be severely curtailed. Airbags or air shocks are commonly used with this type of modification, but they are not an adequate countermeasure for heavy loads added to the rear of the truck. They will stiffen the support at the rear axle, but excessive weight at the rear of the truck may simply bend or break the framerails, much like you can bend (break!) a stick by supporting it in the middle with your knee and pushing down on both ends.

A load-distributing hitch won't solve this problem. Redistributing the tongue load to the front truck axle and the trailer axle won't reduce the stress along the framerails. In such cases it's not uncommon for the framerails to bend or break at the cutout section. Needless to say, this is not easy to repair.

The bottom line here is pretty straightforward. As long as you firmly understand and respect the limitations of your truck, towing a trailer is pretty simple. If you have radically modified the suspension, reduce these limitations by a generous amount (at least 50 percent). And remember, the meaning of sport trucking is to have fun.