First Drive Review

First Drive Review

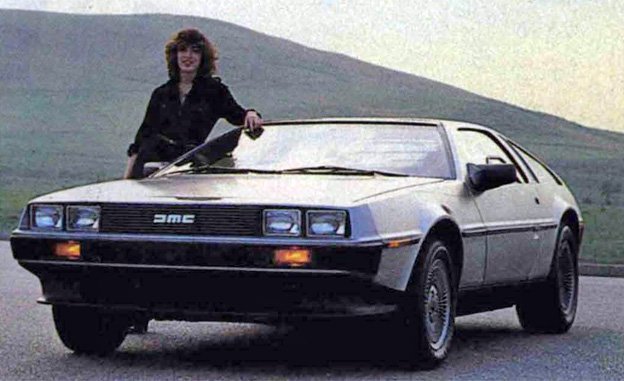

We're slicing through the heavens at Mach 2, steeped to the gills in Dom Perignon and beluga caviar, when the irony of it all slaps me sober. We survived the week of overindulgence, but all sight of our mission—tracking jet-setter John Z. De Lorean as he launches his dream in Northern Ireland—was lost somewhere between the London Ritz and Annabel's Discotheque. A cortege of distinguished American motorjournalists has been diddled again; every one of us is rushing back to the typewriter with more questions than answers.

Will the De Lorean ever make the trip to America? Will the car nuts, depositors, dealers, and investors appreciate it when it gets here? Will the firm even exist a year from now? And most important of all, will John Z., or any mere mortal for that matter, be able to overcome the manufacturing problems inevitable when sixteen-odd snips of stainless steel are spot-welded together to make two gull wings, which in turn must be grafted to a complex, steel-back-boned, plastic-bodied. stainless-skinned silver bullet of a sports car?

The world's hands-on debut of the De Lorean after years of anticipation did resolve a couple of longstanding concerns. First of all, this is unquestionably the most ambitious attempt at running-before-walking ever seen in the variegated history of the auto industry. The backbone frame is easy but expensive, the molded-plastic body complicated and expensive. The gull-wing doors are currently smack-dab in the middle of a no-man's land in terms of manufacturing experience: Mercedes-Benz broke the molds after 1400 300SLs, and Malcolm Bricklin went bust squeezing the next couple thousand winged cars out of his Canadian plant. What's more, the De Lorean is first packed with the power accessories and miles of wiring that go with a luxury ride these days, and only then sealed up in its silver wrapper. To find a more-complex-to-build car, you might try Rolls-Royce, but it crafts only a few thousand units a year and their prices run into six figures.

It's a pity the De Lorean is so tough to build at the moment, because our first impressions are overwhelmingly positive. Giugiaro's rounded-doorstop sculpture looks magnificent in the flesh, and the machinery is good enough to spark a fiery love affair after one quick drive around the block. The De Lorean is not a hard-edged answer to the 911 Porsche, nor is it another fatuous Corvette-clone. And while it stretches the established sports-car performance envelope not an iota, this car is at least happy with itself. The handling is safe and satisfying, the V-6 engine surprisingly mellow in its newest assignment. The interior is roomy, comfortable, and reasonably well thought out. Most important, the De Lorean passes the critical enthusiast's test: it's fun to drive.

You start a trip by yanking smartly at the plastic exterior door handle and avoiding the sharp, eye-poker edges of the gull wing as you fall into the wrinkled-leather seat. The wing retracts easily with a tug on a subway strap that dangles from the inside handle, but it takes a brisk swing to slam home the 90-pound portal with sufficient force to secure both the front and the rear latch. Your next impression is that you're entombed. There's a fat A-pillar uncomfortably close to the center of your forward vision and absolutely no hint of the De Lorean's hood or forward exshield.

The windowsill to the left is at neck level, there's an awkward molding running horizontally through the side glass at eye level, the rear window is full of black, half-closed Venetian blinds, and the bulky backbone runs a few inches inboard of your right armpit. Furthermore, the De Lorean is darker than a snake pit inside, thanks to the modest glass area, tinted windows, and the black-on-black interior trim. (Mr. De Lorean promises silver and saddle upholstery schemes to follow.)

Comfort gradually supersedes most of the interior's initial distress signals: the steering column is two-way adjustable, and there's a hollowed-out section in the overhead part of the door and plenty of space in the wide footwells; so everybody fits, right up to the chairman of the board (six feet live inches, 185 pounds). We're happy to report there is logic to the instrumentation and control layouts. All the gauges are legible, though they're housed in a rather flimsy binnacle. There are rocker switches for the power mini-windows on the center console, wipers on the right stalk, turn signals and a dimmer switch on the left one. The outboard armrests are a tribute to the Porsche 928 with their vent registers, mirror controls, and door handles all contained on sloping ledges that sweep from the bottom of the doors to the top of the instrument panel.

The sound system is an off-the-shelf Craig AM/FM/cassette driving four speakers. Climate controls are centrally located on a black background; the various mode, fan-speed, and air-selection symbols stay black and incomprehensible until they're lit from behind by a turn of the ignition key. One British perversion has crept into the design: the horn actuation has been relegated to the end of the turn-signal stalk. We're also a bit uncomfortable with the seat-belt arrangement, wherein the buckle slides freely through the webbing so the only tension you're allowed across your lap comes from a weak inertia reel.

Michael Loasby, De Lorean's chief engineer, readily admits that price was a deciding factor in selecting the seats. They look Fine, and the recliner mechanism works smoothly, but apparently most of the seat money went into fancy leather upholstery. You ride wedged in place between two fat bolsters that define the seat bottom's perimeter, so your tail never really settles into the comfort of what GM designers so aptly call the "butt pocket."

There's an appropriately throaty vroom-vroom that waits patiently for the end of the sit-down, buckle-up, adjust-the-mirrors ritual. The 130-horsepower, fuel-injected V-6 packed way back in the De Lorean's tail is probably the best-behaved part of the car. It idles without a trace of the syncopation you'd expect from uneven firing intervals. Most of the nasty noises engines make—the whirring of fans, the sucking of air, the clickety-clack of the valvetrain—is either nonexistent or so far removed from your ears that what comes through is the pleasant sound of fine machinery flexing its muscles. The small-displacement, all-aluminum V-6 is slogging through traffic or charging for the six-grand redline. It's unfortunate that neither the five-speed manual (shifted through one rod and one cable) nor the three-speed automatic shares in the enthusiasm. The gearing is much too tall, so the midrange is sluggish.

The top three gears in the five-speed run you so far past socially acceptable velocities that most of the time you're puttering about with the engine a thousand revs below its power band. We saw a flat-out 117 mph (indicated) in Northern Ireland, refuting the factory's early prediction of a 130-mph top speed. Likewise, the De Lorean may have trouble meeting its eight-to-nine-second zero-to-sixty forecast. The end prompting such dastardly tall gearing is a measly 19 mpg in EPA city tests. Weight is the problem: at an advertised 2700 pounds, the De Lorean is 10 percent overweight for the lean life of the Eighties.

You'll feel that fat at the gas pumps, on winding roads, and every time a cheaper sports car leaves you Long ago, when all the doomsayers noticed that a good share of the De Lorean's rear's mass is positioned high and just inboard of the back bumper, they gazed nervously into the future and foresaw treacherous oversteer. Alas, their concerns are unfounded. There's been so much engineering attention to rear-engine shortcomings that most have become attributes. The steering is light with no need for a cumbersome power assist. The dynamic weight distribution, i is perfect for impressive stopping capability, which Mr. Loasby has exploited to the fullest with large and careful balanced brake hardware. The rear engine location even frees up two small cargo holds in an otherwise poorly packaged car: a wide but shallow expanse under the hood and a netted-in playpen behind the seats.

Oversteer, either on or off the power, is factored out with a drastic differential between front and rear tire sizes, inflation pressures. and wheel widths. Furthermore, roll stiffness is biased in such a way that front traction first. Our early pitch-it-and-punch-it stunts on local roundabouts (both wet and dry) could never dissuade the De Lorean from a nose-first plunge to (and through) the limit.

All of which should tell you that there are some good pieces under the skin, the manufacturing team is a bunch of never-say-die adventurists, the Dunmurry plant is full of state-of-the-art production equipment, and the De Lorean car has absorbed plenty of charisma from the man. It will sell for $25,000 (or more) in a steady stream.

There is one big crack in the silver bullet, and it happens to be precisely the size and shape of the gull-wing doors. The five early-built cars we hammered about Northern Ireland were abysmally short of any commercial standard of acceptability: switches popped loose, parts fell off, the rattles had squeaks, doors jammed shut, doors refused to latch, and windows fell out of their tracks. What's worse, there wasn't a single car, either in our entourage or up and down the long assembly line, that you could point to and say, "This is a De Lorean with perfect (or even acceptable) door-to-body fits."

Which is another story in itself. As luck would have it, the first 500 sets of doors were pressed on sloppy prototype tooling. They simply can't be made to fit properly, in our opinion. If we were John Z., the first 500 cars, with those doors, would be permanently banned from sale. Instead, they'd fan out to every dealer across the land to become static displays (with the doors up, so fits couldn't be checked). This would give John Z. the razzle-dazzle he needs, time to regroup, and the opportunity to learn how to build a stainless-skinned gull wing properly.

We hereby hand the onus back to the kind folks at DMC who laid their progress and problems out for all the world to see. Clearly, their future pivots on a single unresolved issue: will the Dunmurry plant rise to the cause and start building the silver bullets John Z. intended? Or will the De Lorean become another Concorde—a technological marvel that turns out to be an economic disaster? Find out for sure in our next installment.