Archived Comparison

From the November 1997 issue

Archived Comparison

From the November 1997 issue

Attempts to compare a modem automobile with an aged counterpart are as futile as those tedious sports-bar arguments over whether Babe Ruth could hit a 100-mph Randy Johnson fastball, or if Rocky Marciano could go toe to toe with Evander Holyfield, or if Emmitt Smith can hit off-tackle as hard and quick as Jim Brown. Apples and oranges, as the old saw goes, and as time marches on, the size, strength, and style of both men and machines are altered to a point wherein historical comparisons lapse into pointless gibberish based only on prejudice and the age of the proponents.

Except in the case of two Ferraris, over a quarter-century apart in age, but amazingly similar in concept and capability. They are the fabled 365GTB/4 Daytona (circa 1968-73) and the current, potentially fabled 550 Maranello, introduced in 1996. Both cars represent the quintessential Ferrari theme; a theme Enzo established in 1947 with his nascent 125 sports car and carried forward in increasingly brash and outrageous forms, i.e., a well-founded chassis cradling a front-mounted, narrow-angle V-12 producing prodigious horsepower from relatively small displacements. The first 1940s cars, the 1.5-liter Tipo 125S and the subsequent 159s and 166s, were modest efforts, intended for dual-purpose road work and competition. It was not until July 1951 that Ferrari surged onto the international scene with his blaringly audacious Tipo 375 Grand Prix car—a normally aspirated 4.5-liter V-12 that broke the back of the all-winning supercharged 1.5-liter 158/159 Alfa Romeos that had dominated GP racing since the end of World War II. From the moment that Froilan Gonzalez won at Silverstone, England, V-12s and the Maranello firm were to be inexorably linked, in legend and in a raw technology that was to produce a series of the most visceral four-wheeled machines in history.

From that lineage, produced by the brilliant designers Gioacchino Colombo and Aurelio Lampredi, came such wonderful V-12 cars as the 1952-54 250 and 375MMs, the 1959-62 250GT SWB Berlinettas, the 1961-62 400 Superamericas, and the titanic 250GTOs. Later came the 250LM and the stunning P3/4 competition cars as well as the GTB—first the 275, and in 1968, the now-fabled 365 Daytona.

To be sure, Ferrari and his engineers built and raced successful straight-sixes, fours, and V-6s (while fiddling in private with other configurations, including Lampredi's ill-fated twin). But it is the V-12 that forms the essence of the Ferrari persona—the company's recent forays into boxer 12s, V-8s, and Formula 1 V-10s notwithstanding. In recent years, the Maranello firm has reestablished its roots, first building the V-12 456GT two-plus-two and more recently a variation on that platform called the 550 Maranello that is thematically a throwback to the wonderful machines of the late 1960s. They signified, in many ways, Ferrari's high-water mark before government regulation and the computer chip radically altered the way cars are built and the way they perform.

Consider that the Daytona and the Maranello are genetically linked in overall architecture. Both are V-12, front-engine machines with transaxles and unequal-length, coil-sprung independent suspensions. Four-wheel vented disc brakes and two-place, grand-touring coupe bodywork with high levels of comfort are common traits, as are stunning performance figures and relatively large dimensions and heavy weight.

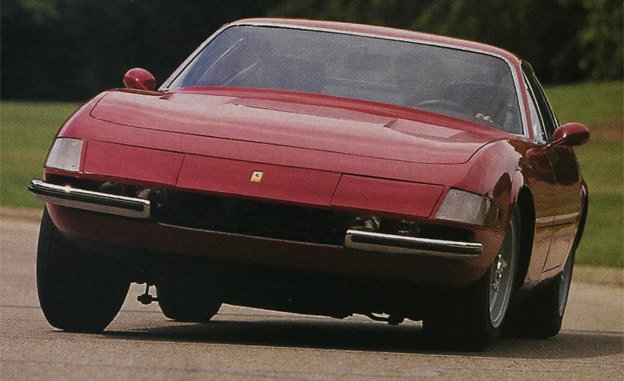

When the Daytona first fell into the hands of the European press following its debut at the 1968 Paris show, universal shock was registered at the car's broad-ranging power. Its arrival on these shores, with its swooping Pininfarina-designed, Scaglietti-built bodywork and dramatic, sharp-edged horizontal clamshell nose (the Euro version had its headlights shielded by plastic; the U.S. Daytona had pop-up models), elicited equal amazement. With only 4.4 liters—or about 5/8ths the size of big-block Corvettes and Cobras—the Daytona generated 342 horsepower at 7500 rpm and 314 pound-feet of torque.

This magnificent powerplant, with its six two-barrel DCN20 Weber carburetors, seemed unaffected by the Daytona's 3465-pound curb weight and propelled it with apparent ease, accompanied by a concerto of gear whines and exhaust shrieks, from 0 to 60 mph in 5.2 seconds and through the quarter-mile in 13.4 seconds at 108 mph. Midrange power was stupefying. The Daytona was capable of leaping from 100 to 150 mph in bursts that left every American muscle car in shameful defeat. (The Daytona demonstrated its awesome capabilities during the November 1971 running of the second cross-continent Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash. Dan Gurney and I drove a 365GTB/4, owned by Kirk F. White, from New York City to Redondo Beach, California, in less than 36 hours. At one point on California's Interstate 10 west of Indio, Gurney reeled off 20 miles with the tachometer wavering at 7100 rpm in fifth gear—nudging the car's claimed top speed of 172 mph. The car was so stable that Gurney drove several of those 20 miles one-handed.)

For years, the Ferrari Daytona remained a benchmark for all truly fast GT cars. Until the new generation of mid-engine Ferraris and Lamborghinis, Porsche Turbos, etc., arrived a decade later, there were but a handful of production automobiles that could touch it, both in overall performance and eye-popping appearance. During the final years of his life, Enzo Ferrari ironically forsook his fabled V-12s (not counting the frumpy 400i automatic) in favor of the potent V-8s that powered his mid-engine GTOs and F40s. It was not until his death in 1988 that the Fiat-based management returned to the V-12 with a vengeance and revived the wondrous design, first with teh two-plus-two 456GT, then with the tumultuous F50, and now with the Daytona's first cousin, the 550 Maranello.

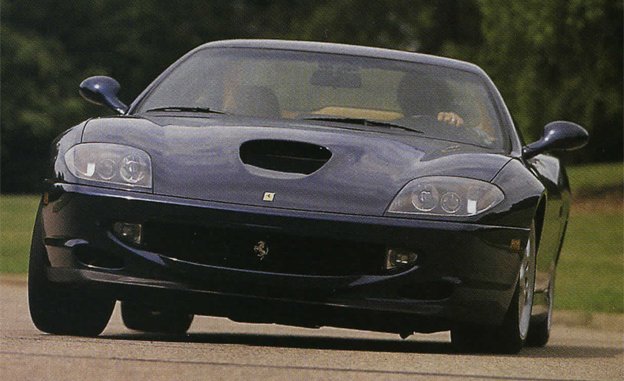

The new car is larger, heavier (by a chubby 447 pounds), faster, and radically more luxurious than its predecessor. But in overall concept the machines are amazingly similar. One might debate the styling of each, the Daytona being the leaner of the two with classical lines that refuse to become outdated. The 550 is bulkier-looking, especially in its derriere, and more derivative. At first glance , the 550's contours are mindful of such contemporaries as the Aston Martin DB7, the Jaguar XK8, or even, heaven forbid, the Ford Mustang Cobra. It is less compelling visually than the Daytona, especially when in motion.

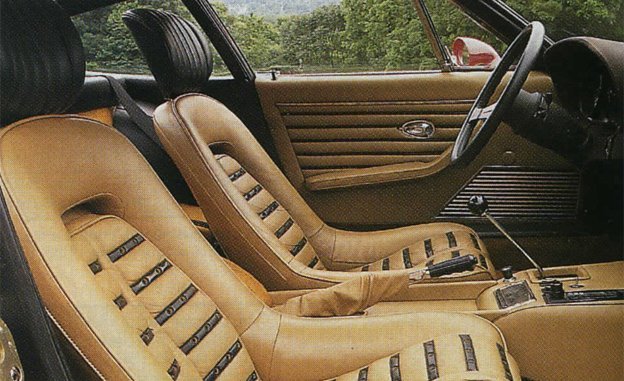

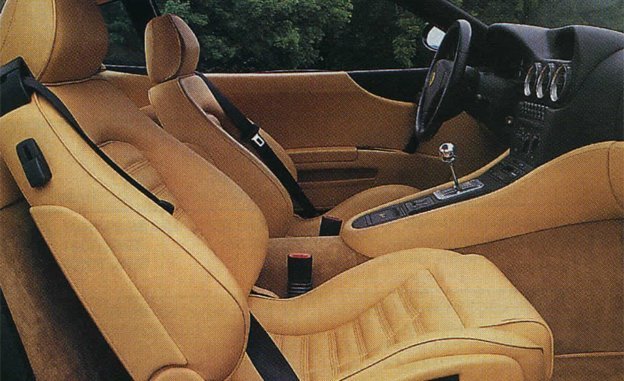

Clearly, the 550 is a technical marvel compared with its cousin, owing to its electronically controlled fuel injection and adjustable traction control, shock absorbers, and anti-lock brakes, plus a plethora of luxury power options. The Daytona has simple, powerless bucket seats, and the most vivid and unpleasant clue to its age is its recirculating-ball manual steering, which serves as a mobile Soloflex at low speeds (although it becomes feathery and precise at highway velocities.) Moreover, its steering wheel resides at a bus driver's angle, recalling the days when such ergonomic decisions were governed exclusively by the bulk of the Commendatore, who mandated all wheel and pedal positions (thereby eliminating all humans of small stature from becoming Ferrari drivers).

With 1.1 more liters of engine displacement than the Daytona (5.5 liters versus 4.4) and vastly more efficient port fuel injection, four-valve cylinder-head design, and intake and exhaust manifold tuning, the 550's engine easily overcomes stringent emissions rules to pump out 458 horses, or 143 more than its cousin. When once considers that this is being produced by a tractable, smooth-idling, normally-aspirate engine, the Ferrari's engineering staff's skill at producing steroid-induced horsepower comes into focus. By contrast, the much celebrated and admittedly vastly less expensive C5 Corvette makes 140 less horsepower from an engine that is 0.2 liter larger in displacement than the 550.

Still, even with outdated Weber carburetors and nonexistent engine-management systems, the Dayton is a potent performer, as was proven during a recent meeting between the two Ferraris in the twisty environs of Cincinnati, Ohio. It was there that we located an excellent example of the Daytona in the possession of Dr. Steve Reubel, an oral surgeon who prayerfully permitted his beloved machine to fall into the ham-fisted hands of this staff for a day of driving and side-by-side comparison with a fresh, factory-provided 550 Maranello.

To the uninitiated, the two cars appear to be contemporaries, albeit with radically different amenity levels. The 550's soft-soap leather interior is sumptuous, whereas the Daytona's borders on spartan. Externally, the 550 is squat, wide, and squarish, whereas the Daytona exudes the long, narrow, svelte lines that inspired such knocks as the Datsun 240Z and the first-edition Mazda RX-7. Both machines emit the resonant rumble of a Ferrari V-12, although the 550 is noticeably quieter, especially at speed. The electronic shock control, coupled with immense tires (255/40ZR-18 front, 295/35ZR-18 rear), make the 550 considerably stickier in the corners, especially when you consider that the Daytona is shod with relatively skinny 215/70VR-15s at all four wheels.

Despite its weight—3912—the Maranello is significantly faster, although in this league of cars, the Daytona can hardly be considered slow. The 550 is, according to our number mavens, a full second faster to 60 mph (4.2 seconds vs. 5.2 seconds) and gets to 100 mph more than two seconds quicker. Both cars bracket 13 seconds in teh quarter-mile (12.7 seconds at 115 mph for the 550 and 13.4 at 108 mph for the Daytona). The 550's top speed is seriously better—188 mph vs. 161, making both among the very fastest production cars extant, regardless of age.

It is in creature comforts that the modern 550 widens the gap—although at a few bucks under $220,000, including license, taxes, registration, etc., it ought to be more comfy. But it is in the checkbook sweepstakes that the Daytona comes into its own. Ferrari built 1412 of these grand coupes (plus 127 Spyders) and most of them remain in service. Not a few regularly appear on the used-car market. A very good Dayton can be purchased for $125,000, according to Keith Martin, publisher of the authoritative Sports Car Market magazine. This means sharp bargaining will get you one of the greatest gran turismo coupes ever made for somewhere around a hundred grand less than a Maranello. Hardly a bargain, but one worth considering for Ferrari cognoscenti whose budgets fall short of the Maranello league.

You won't be Al Gore's pal, you won't have airbags or side door beams or 5-mph bumpers or computer-controlled anything. The Daytona is all manual, save for the windows, but you will be driving a legend, and in this day of the perfect, seamless, and the soulless, that has to count for something.