Archived Comparison

Archived Comparison

“Racing improves the breed.” We used to hear that all the time about cars and car equipment. We even repeated it ourselves occasionally when cheering on various factory competition programs.

But then racing tires got ultra-wide and racing aerodynamics went Boeing and racing budgets grew too many zeros to have anything to do with earth-bound activities. Even more absurd, as the ‘90s dawned, Formula 1 drivers began changing gears with microswitches instead of levers.

That did it! Everyone knows that “rowing the lever” is the essential pleasure of a sports car, so central to the joy of driving that “hot knife through butter,” as a description of shifter action, is automotive writing's original cliché. Take away the lever and you take away the soul of a sports car.

Yet the infidels keep fiddling with their technologies. Can electronics, with its switch clicks, replace the joy of lever snicks? To find out, we've rounded up the sports-car world's two brightest ideas in automated shifting, Porsche's Tiptronic S and Ferrari's “F1-type powertrain management,” reduced to just “F1” for badging simplicity.

Porsche, always quick to take a different path, brought its first “Sportomatic” to the U.S. as an option on the ‘68 911. It was a four-speed manual with a torque converter and an electrically operated clutch—no pedal—that disengaged automatically, and instantly, when the driver touched the shift knob. And he touched it often because this transmission could not shift itself. The hoots are still echoing in our hallways.

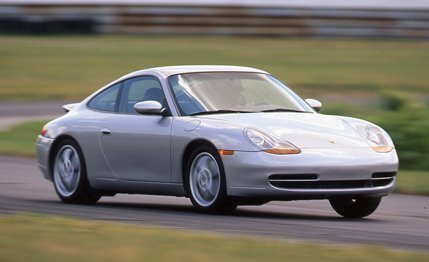

Thirty years later, the Tiptronic S is a five-speed as automatic as the best of them, and smarter than most. It's endowed with special programming to anticipate the wishes of a driver in a sporting mood. For example, if it thinks you're rushing up to a bend with intent to commit cornering, it won't upshift to a higher gear as soon as you lift off the gas and begin to brake. When you wish to call the shifts yourself, that's easy, too. Rocker switches have been placed on the upper spokes of the steering wheel, right where your thumbs fall. Flick up for upshifts, down for downshifts. Use either switch; they respond identically.

The Ferrari F355 F1 has an entirely different approach, very much a descendant of the clutchless-shifting Ferrari 639 Grand Prix car Nigel Mansell drove to victory in Brazil in 1989. This car has the six-speed manual gearbox and dry-plate clutch of the regular F355. But instead of the driver working the lever and pedal to change gears, hydraulic actuators attached directly to the mechanical systems do the pushing and pulling. Contrary to the usual automatic, and to the ancient Sportomatic, there is no torque converter. When the F355 F1 changes gears or brakes to a stop, the computer signals the hydraulics to disengage the clutch.

This automating of the clutch is an old idea, used by a number of European, and particularly French, econosedans in the ‘60s. Automating the shifts to go along with it seems entirely sensible when Ferrari lists the benefits that it sought for its racing cars: no missed shifts and over-revved engines; more performance because faster shifts allow the engine to spend more of its time powering; and more precise handling because the driver can keep both hands on the wheel.

The F1 system goes on the road car as a performance improver, Ferrari says. That it has no clutch pedal, and therefore relieves the driver's burden in stop-and-go traffic just as any automatic would, is merely an added benefit.

About half of what the driver notices with the usual automatic has nothing to do with the transmission. When you engage a gear, notice how the revs drop slightly as the engine takes on a light load. Notice how the engine seems somewhat uncoupled from the wheels at low speeds, allowing the revs to rise above road speed as you accelerate at low speeds. Notice the seamless drop in revs as you brake to a stop. You're feeling the torque converter at work. It's a fluid coupling between the crankshaft and transmission—think of one fan driving another by blowing oil on it—that allows slippage and also serves as a variable torque multiplier.

Slip is essential. It lets you idle against the brake at a traffic light. But it also reduces efficiency. As a way of cutting those losses, modern torque converters lock up—sometimes partly, sometimes completely—as directed by the engine-management computer. Such subtleties usually take place without the driver's notice. For example, the Tiptronic S uses partial lockup to adjust shift firmness under certain circumstances.