Feature Test

Feature Test

In these dark economic times, the number of automakers willing to throw vast sums of money at auto racing has dwindled. Honda, Toyota, BMW, and Renault have either walked away from Formula 1 or reduced their financial commitment. Automakers have cut back the cash they have been spending in NASCAR. And in sports-car racing, only Audi and Peugeot are running fully funded programs in the fastest prototype classes, with more prudent efforts coming from Aston Martin and Honda Performance Development, which uses the Acura badge.

Yet, farther back in the 2010 American Le Mans Series (ALMS) field, where the cost of entry is lower, there is genuine manufacturer involvement in the Grand Touring class. These cars actually look similar to what we see on the street. That involvement can be covert, taking the form of development help to top privateer teams, as Ferrari does with Risi Competizione and Porsche with Flying Lizard. Or it can be a full-blooded factory effort, as with the Chevrolets and the BMWs. It can also be something in between, like the Jaguar-backed RSR team.

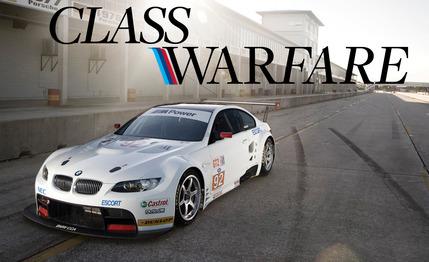

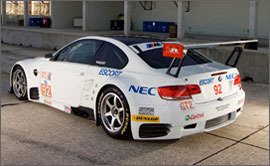

It’s exciting that the best competition in sports-car racing in North America this year will occur between real-looking cars rather than airplanes with wheels. All six of the cars that run in GT—BMW M3, Chevrolet Corvette C6.R, Ferrari F430, Ford GT-R, Jaguar XKR, and Porsche 911 GT3—already look great before the teams add big wings, wide wheel arches, deep front spoilers, and war paint. Dressed for battle, these cars are stunners, none more so than the M3 GT.

According to the rules for Grand Touring–class racing [see below], the M3 has to share a reasonable amount of components with its street cousin. The steel body shell is the same as the regular car’s but with a serious-looking roll cage welded inside. The engine has to retain production castings and the same displacement as the M3’s 4.0-liter V-8, although BMW changed the internal parts, switched to a flat-plane crank, and opened up the ports in the cylinder heads. Output is up 56 horsepower to 470.

The suspension layout is supposed to remain stock, but BMW caught a break from the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO)—it sets the Le Mans (and ALMS) rules— because its strut front and multilink rear setup would have been uncompetitive against rivals that have control-arm suspensions. Hence the M3 GT has specially fabricated control arms at all four corners. The car uses six-piston front and four-piston rear AP brake calipers, but the ACO bans it from using either anti-lock control or carbon-composite rotors. Exotic-looking, 18.0-inch-diameter, forged magnesium Rays wheels are 12.0 inches wide at the front and 13.0 inches at the rear.

The drivetrain itself is substantially different from that of the production car. First, the engine sits lower in the frame and as far back as possible while retaining the standÂard fire-wall location. Whereas the street car’s transmission is mounted in situ with the engine, the racing M3 has a rear-mounted Xtrac sequential six-speed transaxle. Components such as the generator, the air-conditioning compressor, and the starter motor mount to the transmission rather than the engine. We measured a weight distribution of 49 percent in front and 51 in back, confirming a claim from Jay O’Connell, technical director for Rahal Letterman Racing, which runs the cars for BMW North America, the company that initiated the program and funds it. (BMW Motorsport in Munich developed the car.)

Most of the body panels are bespoke carbon-fiber pieces, including the doors, the hood, the decklid, and the front fenders. All of the aerodynamic add-ons, such as the gigantic rear wing, are approved by the ACO. According to O’Connell, BMW caught another break from the sanctioning body, this time in the power-versus-drag department. The BMW is derived from a sedan-based coupe and thus has a much larger frontal area than the pure sports cars it races against. “We have between 7 and 10 percent more frontal area, and even when the M3s are lowered and widened, we’re still putting a bigger hole in the air,” he says. And this means the M3 is allowed to make more power than its peers, using larger air restrictors on the engine’s intake system in order to Âequalize performance, as dictated by the ACO and the ALMS. With all the lightweight pieces, the car weighs in at 2830 pounds, almost 800 less than a stock M3.

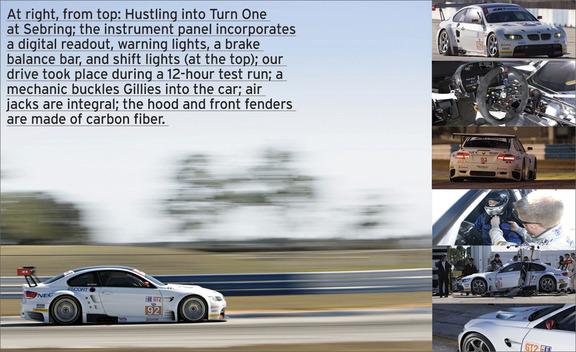

Like most modern racing cars (and ladies of the evening), the cabin is stripped for business, and there’s a lot for the driver to do and take in—enough that BMW gave me a manual to read and digest before driving the car. The steering wheel has a great many buttons on it, including the settings for the traction-control system, the pit-lane speed limiter, the radio, and the turn signals. The dashboard houses the brake balance bar and a digital display that shows revs, lap times, and the car’s vital signs. There’s also a bank of switches to the right of the tall gearshift lever that includes the ignition, the starter, and the air-conditioning controls. And what’s this? A/C? It’s there because a Le Mans rule stipulates that cabin temperatures stay below 83 degrees F unless the ambient is higher, in which case the temperature in the cockpit must match it or be lower. (In the ’80s and ’90s, cabin temperatures in sports-car racing quite often got into the 140-degree range.)

Shifting is simple. Push the lever forward to go down a gear; pull it back to go up a ratio. The clutch is necessary to get rolling out of pit lane but isn’t required on the move. The transmission has a “shift without lift” feature that allows the driver to stay hard on the throttle during upshifts. On downshifts, the electronics automatically blip the gas. The driver shifts when a sequence of lights mounted on the digital dash display goes from green to amber to red.

The driving position is comfortable, if slightly strange, with the seat so far back in the car that your shoulders are almost parallel with the car’s B-pillars. Pronounced bolsters keep the driver’s thighs, hips, and torso in place under hard cornering, in a seat so low that it’s hard to see what’s going on ahead of the front wheels.

When the engine cranks to life, the din envelops the cabin. This M3 doesn’t have mufflers, and when you’re on the gas, the engine sounds like a couple of angry four-bangers at war with each other.

The M3 GT is notably quicker than a stock M3, scooting through the quarter-mile in 11.0 seconds at 129 mph compared with 12.6 seconds at 113 mph for the quickest M3 coupe we’ve tested. With a 0-to-60-mph time of 3.1 seconds and a 0-to-100 time of 6.6, the car’s acceleration is in the same ballpark as the latest 911 Turbo and even quicker than a Corvette ZR1. The engine has a strong power band, and shifts snap off instantly.

According to the data, I’m pulling 154 mph along Sebring’s back straightaway, which doesn’t seem that fast until I have to haul down the car for the ensuing third-gear corner, where the car sticks with 1.7 g, or about 70 percent more than a stock M3. The steering is surgically accurate.

The most impressive aspects of the car, though, are its brakes, its stability and grip in fast corners, and the efficacy of its traction control. As with any race car that generates a lot of downforce at high speeds, the driver can simply mash the brake pedal at the end of long straightaways; however, as speed reduces and downforce diminishes, the driver has to modulate pedal pressure to avoid lockup. The 70-to-0-mph stopping distance of 174 feet is 17 feet longer than an M3’s and 32 feet more than a ZR1’s, but from 120 mph to 0, the M3 GT’s performance is roughly equal to the best Corvette’s, despite not having the benefit of anti-lock brakes. This BMW dares its driver to brake deeper and deeper.

The M3 GT’s powerful downforce is also apparent through the faster corners at Sebring, where the car is as planted as a sequoia. Around the back of the 3.7-mile road course, there’s a double-apex corner that I run at 132 mph, lifting off the gas briefly between the two bends. Factory driver Joey Hand exits at 140 mph. Through the 100-mph-plus Turn One, the M3 hangs on with 1.7 g of cornering force. It would go faster if only I were braver.

Driving a race car with traction control seems strange at first, but it works brilliantly. Factory driver Bill Auberlen suggests using a relatively high rate of intervention—there are six settings—and flooring the gas out of the corners. He cautions, however, that there are a couple of places at Sebring that are so bumpy that it pays to open the throttle progressively, otherwise the tail will step sideways over the bumps, and “you’ll need quick hands to catch it.” After a few laps, I come to terms with matting the gas pedal on corner exits and hearing the engine cut in and out as the electronics nullify any wheelspin. The traction control shortens the dead time between being on the brakes and getting on the gas.

Though handling is remarkably neutral in slower corners, there is a hint of push in faster ones. However, the car is set up stiffly, and Sebring is bumpier than a teenager’s face. As a result, my helmet bounces from side to side against the seat’s head protection.

Still, it’s a great ride. Auberlen says the car wasn’t always this good. “Since we came to Sebring last year, it’s a different car, thanks to a lot of work by the Rahal Letterman guys and by [BMW] Motorsport in Germany.” Tire supplier Dunlop has made great strides, too, he says. In its first year, the M3 was on the GT2 podium in six of 10 races, winning the class once against strong opposition from Ferrari, Porsche, and Chevrolet. The M3 kicked off the 2010 season with a double podium finish at Sebring, where the GT-class battle was the talk of the race, and followed with a podium at Long Beach.

For the manufacturers, the GT class makes a whole lot of sense. It’s relatively cost effective; existing owners and race fans can relate to the cars (which reinforces what the brand stands for); and there’s more chance of technology transfer from a production-based car to street machinery than there is with prototypes. In the long term, if sports-car racing has a serious future, this is where it should lie.

If you spend too much time looking at the rules for GT-class racing, your head may explode. That’s because the world governing body for motorsport, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), recognizes four classes of Grand Touring cars. And there are also national championships run by their own rules, such as the Rolex sports-car series in the U.S. and the Japan Super GT championship.

There’s even some confusion within the FIA structure. That’s because the Stéphane Ratel Organisation (SRO), which runs the FIA world championships, has slightly different rules than the ACO, which governs the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The ALMS takes its lead from the ACO.

The four GT classes are called GT1, GT2, GT3, and GT4. The SRO runs the FIA race series for GT1- and GT3-class cars. The ACO runs GT1 and GT2 cars in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and the ALMS runs GT2 as Grand Touring. GT1 allows the most modifications from standard and also permits relatively low-volume exotics, such as the Saleen S7 and the Maserati MC12, to compete. Carbon-composite brakes, for one, are allowed in this class. GT2 cars are allowed plenty of changes from production, such as carbon-fiber body pieces and wild aerodynamics, but ABS is banned and cast-iron brake rotors are mandatory. GT3 is more tightly controlled: The cars are sold from the factory in race dress. This class bans drivers under the age of 55 who have been paid factory drivers or won Le Mans. Both Audi and Mercedes have recently announced GT3 programs for the R8 and the SLS. Finally, GT4 cars are hardly modified, and the drivers must be amateurs.