Archived Specialty File

Archived Specialty File

"I know it's hard to believe, but some guys who bought ZR-1s, the first thing they tell me, you know, is they're disappointed. They don't care about top speed. They say to me, 'Man, out there at stoplights, I expected this thing was just going to lift its front wheels when I goosed it. But it doesn't.’”

Blasphemy? Maligning the manliness of a Corvette ZR-1 is like accusing Norm Schwarzkopf of wearing pantyhose. Unpatriotic. Except that, in this case, the blasphemer—John Lingenfelter, raised in East Freedom, Pennsylvania—has made a handsome living tinkering with Corvettes for almost 23 years. With eleven assorted NHRA class championships in his hip pocket, Lingenfelter is the quintessential all-American hot-rodder. A hot-rodder with a degree in mechanical engineering from Penn State.

"My goal," says Lingenfelter, "was to increase the ZR-1's output by about 100 horsepower. With no new pieces of hardware. With tailpipe emissions that equaled or were better than stock."

Get a grip, John, we said.

Which deterred this 45-year-old, silver-haired racer not one whit. He is Kenny Rogers on a caffeine jag. During a daylong interview, Lingenfelter deposits himself in a seat exactly once, and then only because he cannot eat his chicken sandwich standing up. Like a pre-schooler, he is in perpetual motion.

"That's an old twin-turbo salt-flats motor over there, and here's a 557-cubic-inch 950-horsepower marine motor for a 41-foot Apache, and you know this dyno measures up to 1450 horsepower but it's not too accurate with anything below 300, and that's my own invention, a tuned-port box; God, with that thing on a 383 [cubic-inch small-block], it just kicks ass. Where are the keys to that white 383? Oh, here. You gotta drive this."

Then he disappears.

Taking notes is nearly impossible. Photographer Dick Kelley says, "Okay, John, just 60 seconds to get the right lens, then I'll take your portrait."

"Great," says Lingenfelter, "time enough for a phone call."

Then he disappears.

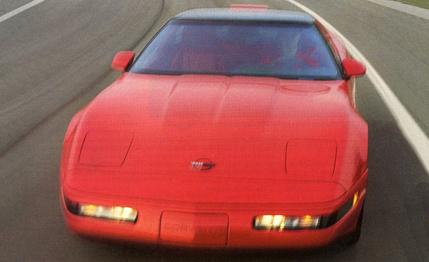

Lingenfelter Racing, on the outskirts of Decatur, Indiana, is housed in an unprepossessing industrial building that might be mistaken for a large laundry were it not for the wail of the dyno and a row of Corvettes parked in the back lot. Inside are 26 employees, all nearly as frantic as Lingenfelter.

C/D readers may recall a Lingenfelter Corvette we tested in December 1989. With a 383-cubic-inch (6.3-liter) small-block mated to an automatic transmission, that car painted black stripes to 60 mph in 4.3 seconds, then tore through the quarter-mile in 12.8 seconds at 109 mph. Which is quicker than a ZR-1 from a car that is nearly $20,000 less expensive. Smog-legal. And it hasn't broken yet.

Not long thereafter, we began hearing from John again. "Of course, I admire the ZR-1," he said. "Thirty-two valves, four cams, 5.7 liters—it's great—but the people who buy these cars always want more power."

"Call us," we said, "if you decide to do something about it." Because Lingenfelter's whole life is more or less a series of low elapsed times, it wasn't long before he called. We met him next to the Decatur K mart four hours later.

"Initially," says Lingenfelter, "I was just messing around, you know, having a look." His idea of messing around involved a $130,000 investment: two ZR-1s purchased for practice. So that he knows what he is working with—some ZR-1s run a lot stronger than others—John's first move is to yank the LT5 engine and measure it on the dyno. Then he lovingly dismantles the thing and sets to work on the heads. He installs titanium retainers to reduce valvetrain weight, recuts the valve-seat angles, then painstakingly blends the ports and polishes the runners until the inner walls shine like Santa Fe silver. Finally, he degrees all four camshafts.