Rick Péwé

Editor-in-Chief, 4Wheel & Off-Road

Photographers:

Tom Morr

Rick Péwé

Editor-in-Chief, 4Wheel & Off-Road

Photographers:

Tom Morr

Brakes are rather simple when you think about it; you stop if you have them and crash if you don't. Somewhere between these two extremes lay the majority of our own brakes, and for the most part, they usually function pretty darn well.

But for those of you who swap brake parts to build custom creations or are saddled with a project that wasn't done right, this story will give you the basics on the three least-understood aspects of a hydraulic braking system that have the greatest impact on how well it works: pedal ratio, master cylinder bore size, and hydraulic line pressure.

One of the biggest braking problems occurs when a stock vehicle, after it's had 1,000 pounds of accessories added and bigger tires slapped on, just won't stop like it used to.

If you've ever noticed the drum and rotor differences between a 1/2-ton and 3/4-ton truck, you know that size does make a difference. The heavier-rated truck is capable of carrying a heavier load, and the larger brakes are properly designed to safely stop that theoretical maximum weight.

Does that mean your overweight Suzuki needs 1-ton-rated brakes for the ultimate in stoppage? No, because the extra weight of the components themselves would negate the advantages. While the ideal situation is to figure out what you need in stopping power, most people are unaware of how to do it. The standard answer is to replace drum brakes with discs, but disc brakes do not necessarily stop better than drums, due to the larger frictional area of drum brakes and their self-energizing feature. However, disc systems definitely work better in the 'wheeling world, because they offer consistent operation in high-heat and wet situations and are much easier to maintain and adjust.

Whether you go with discs or drums, safe, effective braking is the ultimate goal. Achieving that requires either the hit-or-miss approach of parts swapping or a real understanding of the relationship between your foot pressing on the pedal and the tires grabbing the ground.

Probably the three most misunderstood factors that affect braking performance are pedal ratio, master cylinder pressure, and master cylinder volume. If these three items are correct, other issues, such as the type of lining material and brake-biasing procedures, can easily be handled. For example, if the custom brake system on a truck doesn't stop it sufficiently many owners will just throw on better brake pads, when in reality the pedal ratio or the pressure or volume to the calipers may be wrong.

In addition to explaining these braking mysteries, we have also included a few tricks and tips, along with some associated formulas for figuring out how to stop your rig in the real world, that we've learned through our own hit-or-miss upgrades.

But remember, the braking system on your vehicle is one of the most important aspects regarding the safety of yourself and others. If you can't modify the braking system correctly, don't do it at all. It's far better to leave this type of work to the experts than to end up in a ditch, or worse.

Pedal Ratio

Most vehicles have a brake pedal that hangs under the dash on a pivot, with a rod attached beneath the pivot that goes into the master cylinder. The distances between the foot pad, the pivot, and the pushrod are designed to provide leverage. This allows a small amount of foot force (referred to as pedal pressure) to translate into the high amount of hydraulic line pressure needed to stop the truck. On most production vehicles the pedal ratio is preset and nonadjustable; generally it's about 5:1 for manual brakes and 3:1 for power brakes, since they require less effort to activate. But on custom installations these ratios can be completely out of whack, leading to a hard pedal if the ratio is low, or excessively long travel if the ratio is high.

Also important is the stroke of the master cylinder. Most master cylinders have 1 to 2 inches of stroke; the pivot point and the pedal ratio must be adjusted to match the stroke of the master cylinder, otherwise full pressure or complete retraction may not be accomplished. For example, if the pedal is in the full up position against the pedal stop but the master cylinder piston isn't fully retracted, the brakes may still be applied and they may drag. Likewise, if the brake pedal hits the floor or another stop before the master cylinder is fully depressed, full braking pressure may not be available.

PhotosView SlideshowMaster Cylinder Pressure

Most hydraulic brake systems operate at a safe maximum of 1,000 to 1,200 psi, with regular braking pressures below this figure. The hydraulic pressure in the system is a function of input pressure from the pedal and the piston area of the master cylinder. The way to calculate this pressure (P) is to divide the force on the pedal (F) by the area of the piston face in square inches (A), or P=F÷A. Knowing that a 1-inch bore master cylinder has an area of 0.7854 square inches (šR2), and with a known force of 600 pounds on the plunger in the master cylinder, we come up with: 600÷0.7854=764 psi in the braking system. Likewise, substituting a larger or smaller diameter master cylinder bore in this scenario, such as 1 1/4-inch or 7/8-inch, will produce 489 psi or 997 psi, respectively. So a larger volume master cylinder (a bigger bore) will produce lower pressure than a master cylinder with a smaller bore.

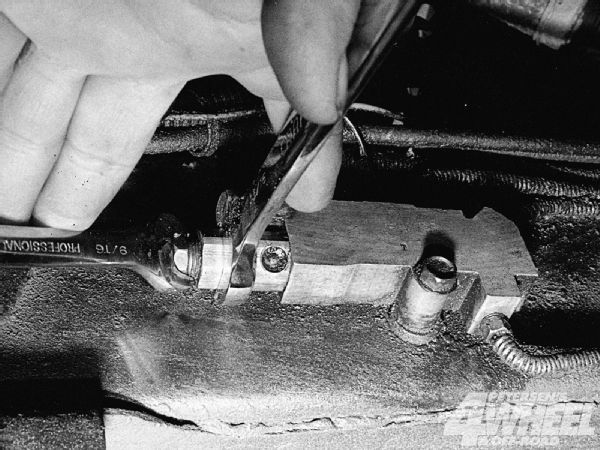

Since most of the braking is done by the front wheels, a proportioning valve is used to limit pressure to the rear brakes so they don't lock up prematurely. This factory unit also includes a metering valve for the front discs and a warning light switch in case pressure in the front or rear is lost, so it is called a combination valve. An adjustable proportioning valve can be a handy item for dialing in the amount of rear pressure on any custom brake setup, but it isn't always necessary.

Since most of the braking is done by the front wheels, a proportioning valve is used to limit pressure to the rear brakes so they don't lock up prematurely. This factory unit also includes a metering valve for the front discs and a warning light switch in case pressure in the front or rear is lost, so it is called a combination valve. An adjustable proportioning valve can be a handy item for dialing in the amount of rear pressure on any custom brake setup, but it isn't always necessary.

Proper pressure, which is critical to the correct function of any braking system, can be adjusted as described with different size master cylinder bores and pedal ratios. A smaller master cylinder can be used if higher system pressure is needed. However, switching to a smaller master cylinder will also increase the pedal travel. If the system can't accommodate this travel (i.e., the pedal hits the floor), then this is not a good option. In that case it might be better to increase the force on the master cylinder by raising the pedal ratio to obtain more pressure in the system.

Master Cylinder Volume

When changing the diameter or the stroke of a master cylinder the volume of fluid displaced is changed as well. But since the volume of a closed system remains the same and brake fluid can't be compressed, the stroke of the cylinder is limited. On any brake system in proper operating condition the pads or the linings are very close to the rotors and drums, so not much movement is needed for them to make contact. After clearances are taken up, pressure rises in the system as the pedal is pushed down, but the actual fluid displacement within the system remains the same, regardless of the diameter of the master cylinder. The volume of fluid displaced equals the stroke of the piston times the surface area, so a larger-diameter master cylinder needs a smaller stroke to displace the same amount of fluid as a smaller-diameter one. This is one case where bigger isn't always better. If the stroke and the diameter of the master cylinder and the pedal ratio can't be changed, then adjusting the pressure within the system can sometimes be accomplished by using larger wheel cylinders or bigger calipers.

Here's a simple formula to determine the volume of displacement necessary to safely operate a brake system. Proper capacity is determined by the equation D=S x A, where D is the total cylinder displacement, S is the stroke, and A is the piston area in square inches. To see how this works, we'll use a theoretical four-wheel disc system where the front calipers each displace 0.075 cubic inch and the rears each displace 0.050 cubic inch. The total volume of all four calipers is 0.25 cubic inch. ([0.075 x 2]+[0.05 x 2]). After multiplying by a safety factor of 100 percent to account for swelling, leakage, and deflection, we arrive at a total of 0.5 cubic inches of needed cylinder displacement. The master cylinder stroke is 1.2 inches, a common length. Solving for the unknown variable, where D÷S=A, we get 0.5÷1.2=0.417, or a piston area of 0.417 square inch. That translates to a bore size of between 11/16 and 3/4 inch (Piston area=šR2).

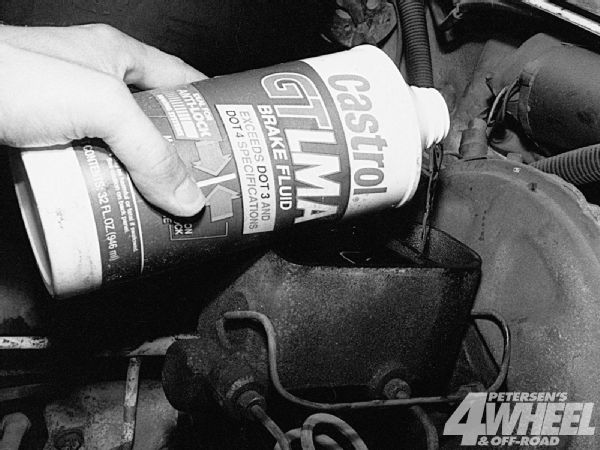

Any brake system must contain the proper brake fluid and be completely bled of air. Even though the new silicon brake fluids don't absorb water like standard fluids, they do have a tendency to compress slightly and give a spongy feeling at extremely high temperatures, such as are encountered in racing. However, if you are plagued by corrosion and water contamination, silicon-based fluid is a good alternative.

Any brake system must contain the proper brake fluid and be completely bled of air. Even though the new silicon brake fluids don't absorb water like standard fluids, they do have a tendency to compress slightly and give a spongy feeling at extremely high temperatures, such as are encountered in racing. However, if you are plagued by corrosion and water contamination, silicon-based fluid is a good alternative.

The End Result

To design and build the perfect braking system for any particular truck, many additional factors must also be considered. The coefficient of friction of the pads or shoes, the brake torque of such, the vehicle's center of gravity and total weight, and so on. Do real people actually sit down and measure all these factors and figure out exactly how to build a brake system? You bet they do! But the old seat-of-the-pants method usually comes into play once the general design work is finished. Most builders set up a rig and then go out and test it on a deserted road with no nearby telephone poles or cliffs. Changing any or all of the aforementioned variables a little at a time is essential to dial-in proper braking for each individual vehicle, especially custom-modified ones.