Thanks to the ever-growing popularity of restored and cloned Max Wedge and Race Hemi-powered '62-'65 Dodge and Plymouth Super Stockers, many builders are quickly learning that the early ('62-'65) cable-operated 727 TorqueFlite does not accept the same torque converter as the later ('67-and-up) lever-operated 727.

The hassle is the cable-operated 727 and the one-year-only '66 lever-operated 727 have a coarse 19-spline input shaft, while the lever-operated '67-and-up successor has a fine 24-spline input shaft. Back in the late '60s and '70s, it wasn't a big deal as most aftermarket torque converter manufacturers offered something for everyone with coarse- and fine-spline high-stall replacements. But its been over four decades since Chrysler made the switch from 19 to 24 splines, and since maybe only one in a thousand 727s in use today is the early style, today's volume-oriented converter manufacturers have pretty much turned their backs on the early design. It just isn't profitable to stock such a low-volume item.

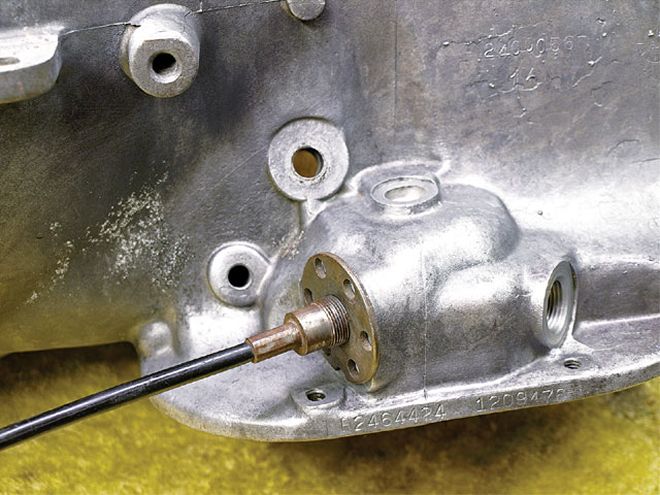

If you see this on the driver side of your 727 TorqueFlite case, it's a '62-'65 cable-operated model ('60-'65 904 baby TorqueFlites look similar). The other end of the cable is connected to the push-button control module inside the car (or a shift lever on console-equipped cars). The push-button control module uses sliding arms with ramps and cams to convert fingertip button inputs into a push/pull force on the cable. The in-out stroke of the cable acts on the valvebody inside the transmission case to affect gear selection. It's a simple bulletproof design that's only compromised by a misadjusted or damaged cable. The circular dial plate is threaded around the shift cable and is used for cable adjustment. Auto industry standardization banned push-button transmission controls on new cars after 1964. In 1965, the cable-operated 727 remained in production for one final year, but it was controlled by a lever on the steering column or by a floor shift on the console. No more buttons.

If you see this on the driver side of your 727 TorqueFlite case, it's a '62-'65 cable-operated model ('60-'65 904 baby TorqueFlites look similar). The other end of the cable is connected to the push-button control module inside the car (or a shift lever on console-equipped cars). The push-button control module uses sliding arms with ramps and cams to convert fingertip button inputs into a push/pull force on the cable. The in-out stroke of the cable acts on the valvebody inside the transmission case to affect gear selection. It's a simple bulletproof design that's only compromised by a misadjusted or damaged cable. The circular dial plate is threaded around the shift cable and is used for cable adjustment. Auto industry standardization banned push-button transmission controls on new cars after 1964. In 1965, the cable-operated 727 remained in production for one final year, but it was controlled by a lever on the steering column or by a floor shift on the console. No more buttons.

So if you want a high-stall 19-spline converter for your cable-operated 727, you won't find it at the local speed shop or in most speed merchant catalogs. Instead, you'll be searching out vintage equipment or spending extra for a custom job based on your existing core.

None of this is a big deal if you're building your '62-'65 B-Body into a free style car-you know, a basic hot rod or bracket bomber. Just swap in a later '67-and-up 727, toss in an aftermarket floor-mounted ratchet-shifter, and you're good to go with access to literally hundreds of available off-the-shelf torque converters.

But if you're a purist and want to keep the super cool push-button transmission controls in your '62-'64 Super Stocker, the whole input-shaft-spline/torque-converter scarcity deal is a real bummer.

Or is it? We got turned onto a neat and simple trick recently by the guys at Bob Mosher's Max Wedge and Race Hemi clone factory. It seems that by swapping a few carefully chosen parts from a '67-and-up 727, owners of cable-operated 727s can keep their buttons and still enjoy the benefit of a readily available, off-the-shelf, high-stall torque converter.

We should let you know that because Mosher's is primarily a restoration shop with a two-year backlog of customer project cars, they're not set up to handle inquiries on the procedure or to accept your transmission for conversion work. Instead, they share this information as a sort of public service and say any competent transmission shop can duplicate the results for you if you're not ready to do it yourself.

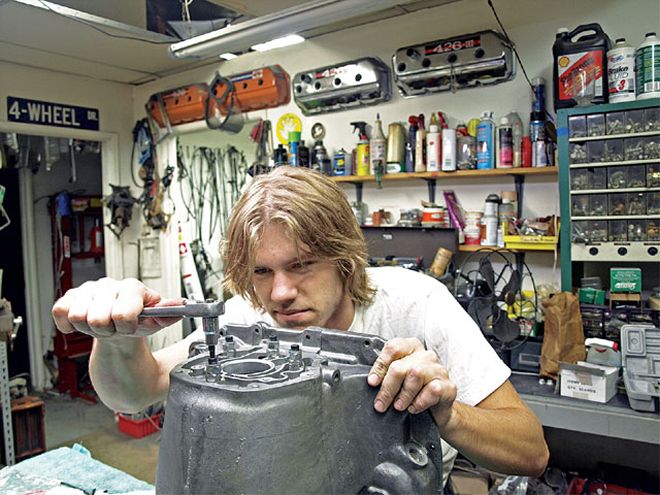

Follow along as Mosher's Steve Benoit outlines the swap and gives some pointers on dialing in your cable-operated 727 TorqueFlite.