When we decide to build a new engine for one of our Mopars, we nearly always want to build an engine that is more powerful and more durable than the engine it will replace. And with the abundance of aftermarket parts available to choose from these days, making more power is easier than ever. Whether running on pump gas or race fuel, normally aspirated or with a power adder, there are plenty of ways to build your Mopar engine to make incredible power. One question we’re often asked is whether or not a supercharged engine is more durable or makes more power than a normally aspirated engine. The answer to this question is not so much which engine is better, since durable and powerful engines can be built either with or without a supercharger, but rather, which technique is best for you. This month we’ll describe the differences of engines with similar power levels, both normally aspirated and supercharged, and you can decide which is right for your Mopar.

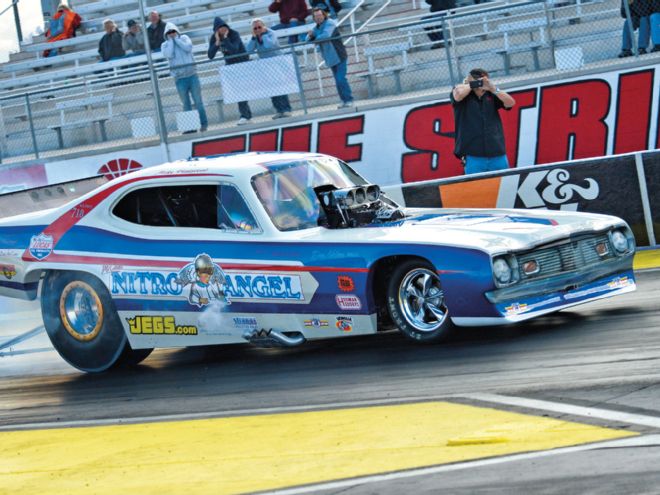

We all know that in the Top Fuel and Funny Car racing classes, superchargers rule the day. That power, however, comes at a price as these engines only last one pass down the quarter mile (actually 1,000 feet) before needing to be rebuilt. The fact is that the Mopars we drive and race don’t need nearly the amount of power that a Top Fuel car does, and building an engine of moderate power for our street or race car can be accomplished in a number of ways. For the purposes of comparison, we’ll describe what it takes to build a Mopar street engine with approximately 600 horsepower, both normally aspirated and supercharged, and the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Basics and Terminology

Both normally aspirated and supercharged engines rely on something called manifold pressure (pressure inside the intake manifold) to get air and fuel into the engine’s cylinders. Manifold pressure is measured in inches of mercury (inHg), which is also the standard by which atmospheric pressure is measured. In a normally aspirated engine, manifold pressure is limited to the pressure of the atmosphere which is measured with a barometer (barometric pressure), while a supercharged engine can boost the manifold pressure by compressing the air that enters the manifold. Weather conditions and altitude affect barometric pressure, but as a universally recognized standard performance calculations are based on a barometric pressure of 29.92 inches of Mercury at sea level.

To convert inches of mercury to pounds per square inch (psi), inches of mercury is multiplied by the factor .49109778. So a standard atmospheric barometric pressure reading of 29.92 equals approximately 14.69 psi, which is what helps engines (and people) breath. To keep things simple, this atmospheric pressure is generally thought of as zero psi, and indicated as such on most automotive pressure gauges. Any pressure above this standard will read as a positive pressure and anything below will read as a vacuum (negative pressure) on most gauges.

A normally aspirated (non-supercharged) engine’s manifold pressure is limited to the barometric pressure in the atmosphere. So at wide open throttle, the pressure in the intake manifold forcing air into the cylinders is the same as the air pressure in the environment, no more, no less. At less than wide open throttle settings an engine’s manifold pressure drops. This pressure drop is defined as manifold vacuum, and is caused by the pistons trying to suck more air into the engine than the throttle opening will allow. So if a certain part-throttle setting causes a manifold pressure of 19.92 inches of Mercury, and the barometric pressure is 29.92 inches of mercury, the engine is said to be making 10 inches of vacuum. This theory of vacuum applies to both normally aspirated and supercharged engines.

The difference in a supercharged engine is that the supercharger (no matter what style), compresses air and forces that air into the intake manifold, allowing manifold pressures greater than atmospheric pressure. In automotive applications, this additional pressurized air is referred to as boost, and the pressure is expressed in pounds per square inch (psi) instead of inches of mercury. Converting this extra five inches of Mercury to boost (psi) equates to 2.45 psi of boosted, or compressed air.

Supercharger Advantages

There are some obvious advantages of running a supercharger on your engine, and the biggest advantage is definitely the power potential. The performance of an engine is directly related to the amount of air and fuel the engine takes into its cylinders, so the ability to force pressurized air into the engine dramatically increases the amount of power the engine is capable of, and the bigger the supercharger, the bigger the power. Even a small supercharger can get the average pump gas street engine to 600 horsepower pretty easily, and more boost equals more power. Another advantage of adding a supercharger is that the engine and drivetrain components just need some simple upgrades but not wild modifications.

Because the supercharger is forcing air into the engine, aggressive cam profiles, cylinder head porting, or high compression ratios aren’t necessary to achieve big power levels. In fact, supercharged engines respond to camshafts with wider lobe separation angles, which are conducive to smooth idle and big midrange torque as well. And since the supercharged engine can make impressive low end and mid-range power, a high rpm stall converter or low gear ratio isn’t usually necessary for quick acceleration. In fact, we’ve installed superchargers on fairly stock engines and with moderate (4-6 psi) levels of boost factory driveline components can survive just fine. And since the supercharger doesn’t stress engine components during low rpm operation at no or low boost levels, supercharged engines tend to remain reliable and durable for extended periods if maintained properly.

Supercharger Disadvantages

While the benefits of supercharging can be great, these benefits come at a cost in terms of expense and complexity. Adding a supercharger to a car that wasn’t originally equipped with one from the factory (and no Mopar was), means adding equipment under the hood that not only takes up space, but generates heat as well. Also, since most automotive superchargers are driven from the crankshaft, either by a belt or gear-drive system, the normal engine accessories like the alternator, power steering pump, water pump, etc. nearly always need to be changed or modified in terms of position and belt routing. Compressing air also generates heat, so supercharger kits often come with an intercooler, which must also be placed in the engine bay, usually in front of the radiator, to cool the intake charge back down prior to ducting the air into the engine. The car’s fuel system including the pump and injectors (on fuel injected vehicles), or carburetor (on carbureted vehicles), must also be up to the task as any time more air is supplied, more fuel must be provided as well to ensure the proper combustion mixture. Tuning of the ignition timing is also a consideration, as the additional cylinder pressures experienced with supercharging will require a reduction in total advance to prevent detonation.

Of course as boost pressure increases, additional modifications such as forged pistons, forged connecting rods, and a forged crankshaft become necessary to ensure engine durability. In extreme cases, a supercharged engine may need to be “O-ringed” which involves installing a stainless steel wire on the deck or head surface around the combustion chamber, which is used with a copper head gasket to ensure combustion chamber seal in highly boosted applications. And while supercharged engines generally don’t need aggressive stall converter rpm or gear ratio, at some point the converter, transmission, U-joints, gears, and axles will need to be upgraded to handle the additional torque that the engine is making.

05 Since high-powered, normally aspirated engines generally have a narrower torque and power curve that happens at a higher rpm, you’ll likely need a looser stall converter and/or higher rear gear ratio for optimum performance. "> <strong>05</strong> Since high-powered, normally aspirated engines generally have a narrower torque and power curve that happens at a higher rpm, you’ll likely need a looser stall converter and/or higher rear gear ratio for optimum performance.

<strong>05</strong> Since high-powered, normally aspirated engines generally have a narrower torque and power curve that happens at a higher rpm, you’ll likely need a looser stall converter and/or higher rear gear ratio for optimum performance.

Normally Aspirated Advantages

Simplicity is likely the biggest advantage of a normally aspirated (non-supercharged) performance engine as there is no supercharger, ductwork, intercooler, or drive system to fit into the engine bay. Making horsepower in the 600 range without forced induction can be tricky, however, and often requires some fairly major modifications to the engine both internally in the way of a stroker kit and/or forged internal components, and externally in the way of aftermarket cylinder heads, headers, and induction. To make high power levels without supercharging or other power-adder systems like a turbo or nitrous, an aggressive camshaft is necessary and the engine must be revved higher which sacrifices low and midrange torque.

Lower cost is another distinct advantage of building a normally aspirated engine as superchargers and associated equipment like drive kits, intercoolers, ducting, and accessory drives can be expensive. By choosing not to add a supercharger to an engine, the money saved can be applied to the engine itself as items like high-flowing cylinder heads, headers, high-compression pistons, a roller cam and lifters, and other items necessary to make big power without the benefit of forced induction. Achieving high power levels without a supercharger generally requires a cam with narrower lobe separation, more duration, and higher lift to allow the engine to rev higher and ingest more air and fuel, so oil system modifications can be necessary as well.

Normally Aspirated Disadvantages

Normally Aspirated engines are limited to atmospheric pressure when it comes to manifold pressure, so power must be optimized in other ways. Extra expense must be spent on cylinder head porting, and more aggressive cam profiles require heavy springs which will cause quicker wear to guides and seats, as well as more frequent spring replacement. Compression levels must also be higher in a normally aspirated engine, which causes more aggressive wear to rings and rod bearings. The higher compression required in a normally aspirated engine also leads to higher cylinder pressures any time the engine is running, not just when under boost like a supercharged engine, requiring more frequent maintenance or freshening of the engine comparatively.

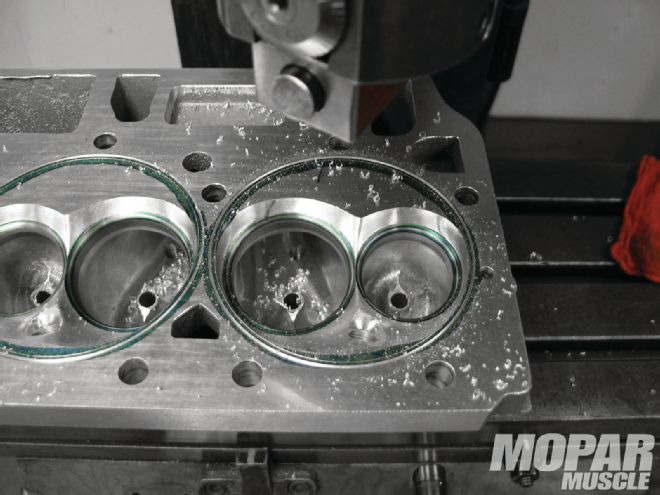

08 There are some special considerations when a supercharger is used, such as combustion chamber seal. In high-boost applications, it may be necessary to machine the head and block for stainless steel “O-rings” and copper head gaskets. "> <strong>08</strong> There are some special considerations when a supercharger is used, such as combustion chamber seal. In high-boost applications, it may be necessary to machine the head and block for stainless steel “O-rings” and copper head gaskets.

<strong>08</strong> There are some special considerations when a supercharger is used, such as combustion chamber seal. In high-boost applications, it may be necessary to machine the head and block for stainless steel “O-rings” and copper head gaskets.

A second disadvantage of a powerful normally aspirated engine is the requirement of parts like a loose stall converter or high gear ratio differential to optimize the performance of the vehicle. Since normally aspirated engines generally make their peak torque and horsepower at a higher rpm level, and in a narrower rpm band than a supercharged engine, the gearing of the car and stall speed of the converter become much more important. Often the higher gear ratio required will lead to high engine rpm when cruising on the highway, causing more aggressive engine wear. Of course an overdrive of some sort can alleviate this issue, but then the expense of the overdrive transmission must be added to the cost of the build.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is not to draw a conclusion as to whether supercharging is better or worse than building a powerful normally aspirated engine, but rather to give you the information so you can decide which is right for your Mopar. For some of us, having a fast car that looks fairly stock is a desirable aspect of a vehicle build, so a normally aspirated engine may fit our needs better. For others, the whine of a supercharger and the intimidating look of a blower sticking through the hood may be just what we’re after, and the broad power band of a boosted engine can certainly be worth the expense. And if you’re still undecided, we suggest building one of each!