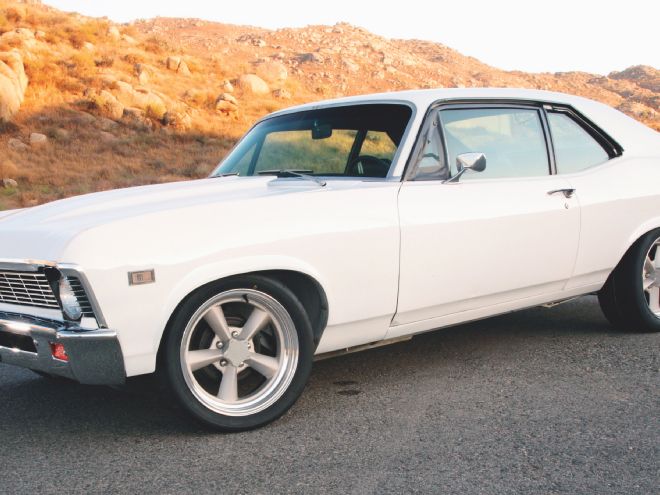

Any way you slice it, 3.08:1 rearend gears just scream absolute wimpiness, especially when they’re bolted inside a fortified Moser 12-bolt rearend. That’s not exactly the kind of thing that impresses the lawn-chair-and-spray-bottle crowd on cruise night, but it’s precisely the setup we opted for in our 1968 Chevy Nova project car. Please keep the granny-mobile jokes to yourselves because there’s good reason for this madness. Last we checked, thanks to the impoverished motoring public, Big Oil execs are frantically trading up for bigger hangers in which to store their rapidly growing fleet of private jets. While gas isn’t cheap, and burning less of the stuff contradicts the very essence of hot rodding, there’s nothing wrong with saving a few bucks at the pump as long as it doesn’t compromise performance. Interestingly, one of the best ways to accomplish this without going broke is by using 50-year-old technology. The wizardry in question is called a variable-pitch torque converter, and adapting it for use in GM transmissions is remarkably straightforward.

From 1965 to 1967, GM installed switch-pitch torque converters in many of its TH400 transmissions. This arrangement hydraulically alters the angle of the fins on a converter’s stator, thereby increasing or decreasing stall speed by as much as 1,000 rpm on the fly. That’s like being able to swap transmission or rearend gear ratios instantaneously while driving down the road. With the luxury of having a high-stall, switch-pitch converter that magically tightens up at cruising speeds, the net effect is brisk off-the-line acceleration even with a freeway-friendly ring-and-pinion set. For example, in Third gear our TH400-equipped Nova—with its 3.08:1 rearend gears and 255/40-17 rear tires—turns 2,700 rpm on the freeway at 65 mph. Now let’s say we were to upgrade to a 4L80 overdrive that needs shorter 3.73:1 rearend gears to compensate for a tighter, non-variable pitch converter. Even with the 4L80’s 0.75:1 overdrive ratio, the motor would still turn 2,500 rpm at 65 mph. The question is whether or not that 200-rpm difference in cruise rpm justifies the added expense, weight, and complexity of a computer-controlled overdrive, and we just didn’t feel that it was worth it in our Nova.

Like many of the best factory innovations that the Big Three have spawned over the years, rumor has it that GM ceased production of switch-pitch converters due to their high manufacturing costs. This limited production run can make finding parts a challenge, but fortunately shops like Phoenix Transmission Products in Weatherford, Texas, are well stocked with switch-pitch hardware. “A variable-pitch torque converter can be fitted on just about any TH400 transmission,” says Greg Ducato of Phoenix. “The only parts that need to be swapped out for a switch-pitch conversion are the stator, pump, input shaft, and the converter assembly itself. The high-stall mode is activated by an electric solenoid that’s mounted on the pump. From the factory, the solenoid was often activated by the carburetor linkeage, but on hot rod applications you can mount a switch wherever you want.”

Despite our best efforts, we haven’t been able to break a Phoenix-built transmission in any of our in-house project cars, including our ’75 Laguna and ’93 Mustang. Naturally, we didn’t hesitate to give Phoenix a call when it came time to build a fresh TH400 in our project Nova, and we tagged along as Greg put it together. So here’s an up-close look at what it takes to get variably pitched.

Where the Money Went Item: PN: Price: Phoenix TH400 PTP400SS $1,231 Switch-Pitch upgrade N/A $550 Crossmember RCF1-400 $219 Kick-down kit KD2400HT $78 Total: $2,078