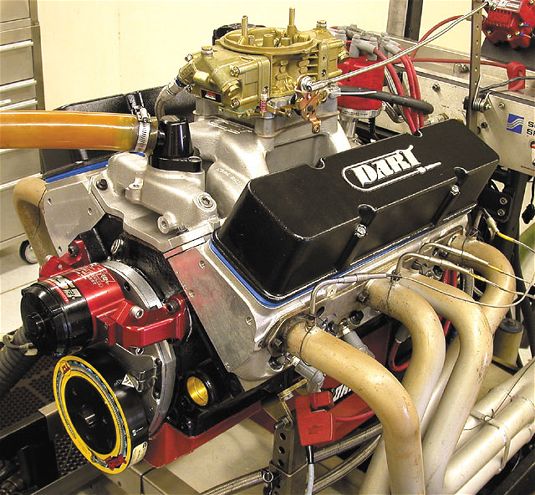

Here's the big difference between this and a typical magazine motor: We ignored horsepower and went straight for big torque and total driveability. And to make it interesting, we did it with a small-block--a 450ci small-block--on 87 octane. How does 500 lb-ft at 2,000 rpm sound? That's just where it gets started. This idea first hit us about 10 years ago when GM introduced the Rocket Block, an Olds-branded casting designed specifically for big-inch, small-block drag race applications with a raised camshaft location and 0.800-inch-wider-than-stock pan rails, both designed to clear long-stroke crankshafts. The Rocket was also available with a deck height of 9.325 inches, 0.300 taller than the blueprint spec of a stock Chevy block. At the time, those features demanded a bunch of fabricated parts that made the engine impractical for a backyard wrench to assemble or afford. Then GM discontinued the Rocket. Today, Dart offers the Iron Eagle small-block casting with all the features of the Rocket block, and several aftermarket companies have the parts needed to easily slam together a big-inch small-block. So we did. Watch this.

Four Ways to Use This Engine

* Sleeper: Dumb-down the look by grinding the Dart logo off the block, adding some stock valve covers, and fogging everything basic orange or GM Blue. A near-stock idle makes it believable as a smog 350.

* Late-Model F-Car: Whether you've got a third-gen or an LT1-powered fourth-gen Camaro or Firebird, you may want huge power without the lumpy idle of a stout 383 and sans the extensive swap hassles of a big-block. Our 450ci small-block could hide under a TPI intake, pose as a 305, and run like a Rat.

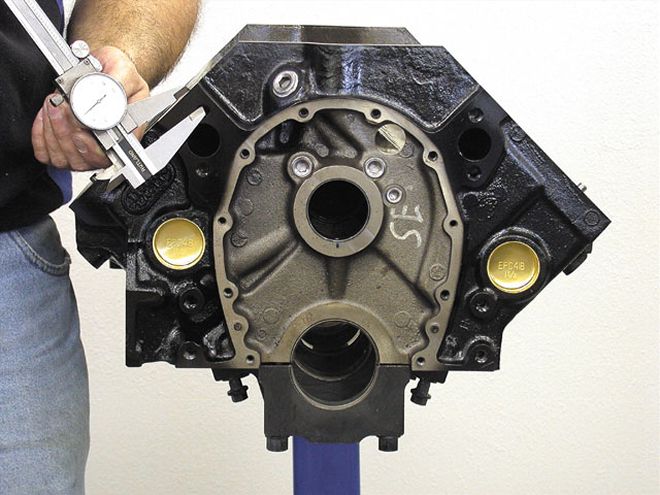

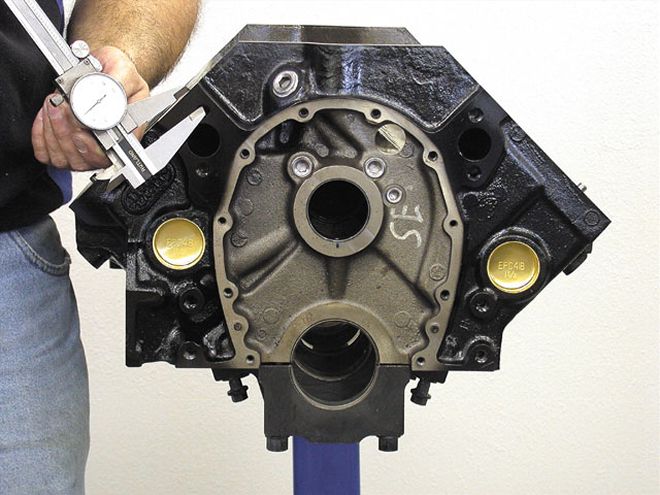

The Dart Iron Eagle block PN 31122221 has an optional 9.325-inch deck height (crank centerline to cylinder-head surface). A stock Chevy small-block is 9.025 (as is the low-deck Iron Eagle), and the difference can be spotted by observing the distance from the water-pump hole to the deck surface. Another Iron Eagle feature is the camshaft centerline that's moved up and away from the crank centerline by 0.391 inch. Both these features allow longer strokes than would otherwise be practical.

The Dart Iron Eagle block PN 31122221 has an optional 9.325-inch deck height (crank centerline to cylinder-head surface). A stock Chevy small-block is 9.025 (as is the low-deck Iron Eagle), and the difference can be spotted by observing the distance from the water-pump hole to the deck surface. Another Iron Eagle feature is the camshaft centerline that's moved up and away from the crank centerline by 0.391 inch. Both these features allow longer strokes than would otherwise be practical.

* Street Rod: Small-blocks fit easier in everything from '32s to fat-fenders, and will cool and handle better, too.

* Jeep: Not the world of most readers, we know--but small-blocks are the single most common swap, and any Jeep can use axle-twisting torque.

Low-Deck vs. Tall-Deck 454 Mice

The inevitable question: How does our Dart 450 differ from the 454ci small-block crate engine we tested in the July and Sept. '03 issues? That World Products engine made more horsepower than our Dart-based engine, but that's due to more compression, cam, intake, and carb. Given those variables, either brand of engine can make the same power. What's more significant are the structural issues that might affect your specific needs.

The World 454 uses a block with a standard deck height and a standard cam location. Almost all the parts are standard Chevy stuff, you don't need a remote oil filter, and there are no header-to-chassis-fitment problems that may arise with the Dart Iron Eagle's 0.300-inch-taller block height.

The other feature for long strokes is the wider-than-stock crankcase, with each pan rail moved outboard 0.400 inch. To accommodate this change, the Iron Eagle (right) does not have a pad for a spin-on oil filter like the one on the driver side of the stock block (left), and the dipstick is relocated to the oil pan. Note the Iron Eagle's steel main caps; the rear cap accepts a stock-type wet-sump oil pump.

The other feature for long strokes is the wider-than-stock crankcase, with each pan rail moved outboard 0.400 inch. To accommodate this change, the Iron Eagle (right) does not have a pad for a spin-on oil filter like the one on the driver side of the stock block (left), and the dipstick is relocated to the oil pan. Note the Iron Eagle's steel main caps; the rear cap accepts a stock-type wet-sump oil pump.

The World engine has a huge bore of 4.250-inch with a stroke of 4.000. Conversely, our Dart-based combo uses a smaller 4.165-inch bore with a longer 4.125-inch stroke. Since both blocks have stock Chevy bore centers of 4.400-inch, the big-bore World 454 only has 0.150-inch of iron between each cylinder. That's narrow enough to require special head gaskets that are not recommended for high-compression, nitrous, or supercharged applications. The smaller-bore Dart block has 0.235-inch between the cylinders, use standard head gaskets, and can be O-ringed if you really want to step on it.

If you choose to build your own low-deck 454 small-block with a 4.250-inch bore, you'll need custom pistons (it's tough to find shelf slugs bigger than 4.185-inch). Also, 4.250-inch is probably the limit of the block's capacity for overbore. By using the raised-cam block to accommodate a longer stroke, you can get the big displacement using a smaller bore so there's more meat left for future rebuilds and so that you can use shelf pistons.

There's also the issue of cam-to-connecting-rod clearance. With the non-raised-cam block, a 4.000-inch stroke is the absolute maximum you're gonna squeeze in there. A stroke that big in a standard block requires connecting rods that are compact at the big end plus a small-base-circle cam to avoid cam-to-conrod interference. Roller cams with radical ramp rates are even more difficult to fit. Obviously this is not an issue if you buy the crate engine, but you need to know this if you're building from scratch or plan to swap cams later. However, our raised-cam Dart block had no cam-to-con-rod concerns with the 4.125-inch stroke, steel Lunati rods, and either of the Comp roller cams we ran in this story. Dougan's also tested a Comp solid roller with 0.700 lift and 256/260-at-0.050 on a 108 LDA, and it fit easily. By using custom cam profiles and carefully profiled rods, we've seen guys fit as much as a 4.250-inch stroke in raised-cam blocks.

Jeff Jacobs at Dougan's Racing Engines pointed out that the Iron Eagle is intended for dry-sump oiling race applications and does not come with oil drainback holes in the lifter valley. Since this was a street engine with drainback and cam-oiling needs, he drilled these holes, positioning them to ensure they did not intersect the bottoms of the lifter bores.

Jeff Jacobs at Dougan's Racing Engines pointed out that the Iron Eagle is intended for dry-sump oiling race applications and does not come with oil drainback holes in the lifter valley. Since this was a street engine with drainback and cam-oiling needs, he drilled these holes, positioning them to ensure they did not intersect the bottoms of the lifter bores.

Build It Badder

The bummer about a large-displacement small-block is that even the best 23-degree (standard small-block Chevy style) cylinder heads may not be able to flow enough air for a high-horsepower naturally aspirated combo. A 13.0:1-compression 454 big-block can easily top 750 hp with average rectangle-port heads; that'd be a push with conventional heads on a 454 small-block. However, Dart offers both 16- and 18-degree Race Series heads and the exceptionally trick Little Chief 11-degree heads with canted valves and asymmetrical intake ports. They flow over 400 cfm at 0.900 lift. Then you'd have a serious mini big-block.

Even more good news: With all those cubic inches underneath standard small-block heads, it's easy to make huge compression with flattop pistons. For example, the engine in this story would have 12.3:1 with flattop pistons instead of the 36cc dishes. Use Dart Little Chief heads with 37cc chambers and you'd hit 15.0:1 using pistons with 18cc of valve reliefs for the sensibly huge cam you'd obviously choose. Wicked!

The Naturally Aspirated Dyno Test

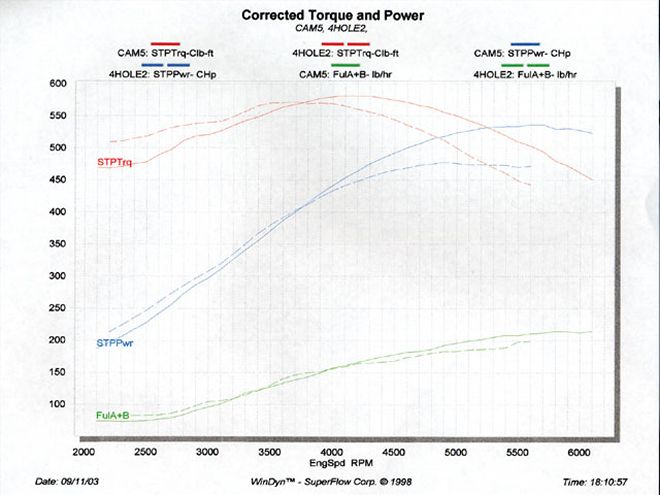

Keeping in mind that we wanted an absolutely smooth idle, huge torque, and zero-hassle driveability, we started out with a miniature hydraulic roller cam. And since we had trouble living with ourselves for choosing the tiny stick, we also tried a big one. Here's how it went.

Comp Cams XE270HR: This one's got 218/224 degrees of duration at 0.050 tappet lift, a 110-degree lobe separation, and lift of 0.528/0.535-inch. That's pretty tiny, proof of which was the no-load idle of 600-700 rpm with no lope whatsoever and a vacuum reading of 16-17 inches. That'll run any power-brake system, run smoothly with an EFI setup, and will sound like a stock 350 to anyone you want to fool. With the 9.3:1 compression and aluminum heads it'll never ping on 87 octane, though we did crank the timing to a total advance of 38 degrees. That's a bit high, indicative of the reduced efficiency of the low compression. This would be a safe 91-octane engine with another point of compression, and would make roughly 4 percent more power at 10.25:1.

Power? The mild XE270HR delivered a peak of 480 hp from 4,900 through 5,400 rpm and a torque peak of 571 lb-ft at 3,700 rpm. More significantly, the small-block never made less than 500 lb-ft from a very low 2,000 rpm clear through 5,000 rpm. That means 500 lb-ft right at the stall speed of a very mild torque converter, and easy 11-second times in a heavy car with freeway gears. And this engine could take a massive shot of nitrous without hurting itself. Think about it.

Comp Cams XE294HR: Since we're bottom-of-the-page cam guys, we also had to try a roller grind with 242/248 degrees at 0.050, a 110 LDA, and 0.571/0.599 lift with 1.6:1 rockers. A bit big for 9.3:1 compression, but it idled at 800-900 rpm with 12 inches of vacuum--still daily driveable, in our opinion.

The effect on the power curves is the textbook-perfect example of what you'd expect from installing a bigger cam. Look at the graph and you can see that the shapes of the curves for the XE270 cam (dotted lines) and the XE294 cam (solid lines) are very similar, but they pivot away from each other at the point defined by 3,750 rpm. Predictably, the small cam makes more horsepower and torque below 3,750, and the bigger cam makes more power after that point. The longer duration of the bigger cam moves up the rpm at peak torque by a few hundred rpm. Since horsepower is a function of torque and rpm, and since the distance between the torque and the power peaks is about 1,500-1,800 rpm, the engine will make more torque at higher rpm and therefore make more peak horsepower. Specifically, the larger Comp XE294 made 582 lb-ft at 4,100 rpm and 536 hp at 5,700. Interestingly, the actual peak torque value only changed a little bit, but the horsepower jumped by 56 points. On the downside, the big cam gives up as much as 40 lb-ft at points below 3,000 rpm.

Iron Eagle Special Parts

If you're considering the price of an engine built with a stock engine block and a China-made crank and rods, our 450-inch will be way more expensive. But if you compare the prices of the custom Iron Eagle parts with conventional-style components of the same top quality that we used in this buildup, then going big will run you about an extra $500. Here's the list of all the special parts you'll need for an Iron Eagle block compared to a standard block, plus the part numbers of the specific components we used.

* Spread-rail oil pan (Moroso PN 20193)

* Raised-cam timing set (Comp Hi-Tech PN 3146KT)

* Longer, big-block-style oil-pump driveshaft (ARP 135-7901)

* Big-block-style fuel-pump pushrod (ARP 135-8701)

* Intake manifold spacers (Dart PN 622100002)

* Remote oil filter (Moroso Omni Filter PN 22285)

* Slip-collar-style distributor (MSD PN 85561)

* 2.375-inch, Ford FE-style rear cam plug

* Line-bored 400-Chevy-style rear main seal (Fel-Pro 2909)

Forget 87 Octane, Make 700 LB-FT

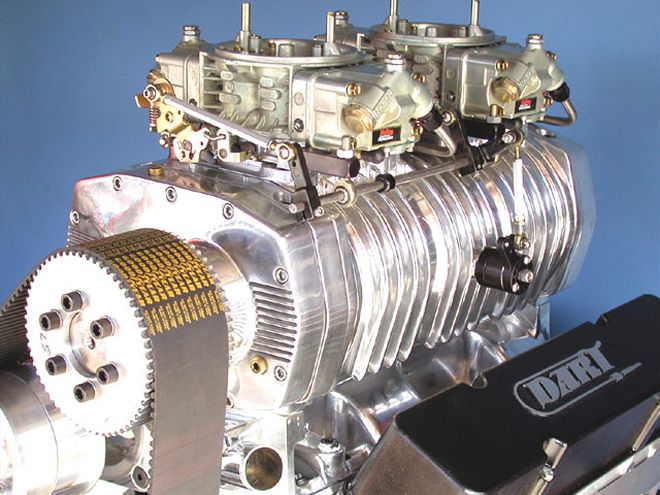

You know you're sick when a naturally aspirated 536 hp and 581 lb-ft aren't good enough. We considered the 450's 9.3:1 compression and the stout Dart/Lunati short block and realized that boost had to happen. Since low-rpm torque was the quest, we pushed the centrifugal aside and yanked a big ol' Roots huffer off the shelf.

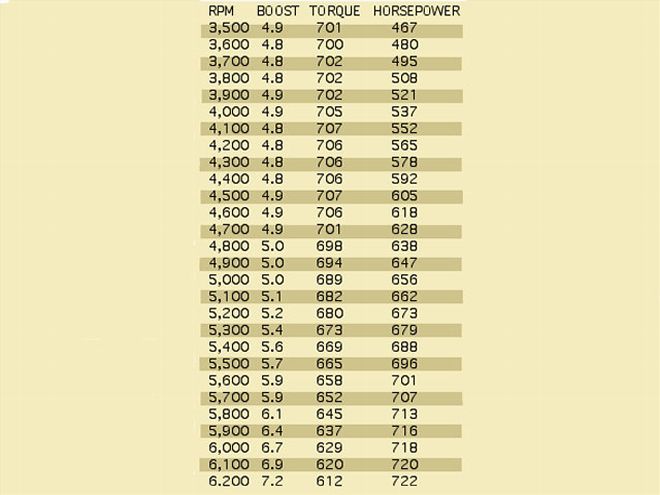

Sadly, the 420ci Holley MegaBlower that we tested was recently discontinued, but Weiand still offers both 6-71 and 8-71 GMC-type lungs for small Chevys. We feel that either one can match the power of the MegaBlower, which shoved our mega Mouse to 700 lb-ft forever and (oops ... we really didn't mean to) 722 hp at 6,200 before the valves floated. Way flat torque curve! The improvements over naturally aspirated were a ludicrous 120 lb-ft and 190 hp. It probably makes 600 lb-ft right off idle.

The camshaft for this test was the same Comp Cams XE294HR we had installed in naturally aspirated trim. The carbs were two Holley HP, 750-cfm blower carbs (PN 0-80576) that were jetted perfectly right out of the box, and we dialed the timing back to 30 degrees total. On 76 Products 91-octane pump gas, there was no hint of detonation with the blower 9 percent underdriven for 5 pounds of boost at peak torque (4,100 rpm) and almost 7 pounds at peak horsepower (6,200).

Basically, the engine was way happy. It still idled at 800 rpm and 12 inches of vacuum and seemed perfectly driveable with the low-maintenance hydraulic roller cam. This would be a nasty, reliable daily driver that could easily live with a low-stall converter and some highway gears but still tug your kidneys into the trunk at the tickle of a toe. We envision absolute death in the likes of a '32 roadster.