'The nature of the automotive journalist is one of cynicism. Tell us that something's been made stronger, faster, or just generally better, and we'll initially assume that it really hasn't. Snake oil has a way of finding us, and if we don't sniff it out, you berate us.

That's not to say we can't be persuaded to consider the possibility that the wares in question actually do have something to offer. It took Michael Demurjian, vice president of sales and marketing for Mikronite Technologies, only a few minutes to gain our full attention at the latest SEMA bonanza. We were standing in the Crane Cams booth as he explained the Mikronite process and its benefits. That this company has merged with Crane lent credence to his assertions, as did the detail in which he explained it. In short, the Mikronite process is a surface treatment that claims not only significant increases in component strength but also, in some instances, an improvement in efficiency through reduced friction. Naturally, we were intrigued and needed to know more.

What Is Mikronite?

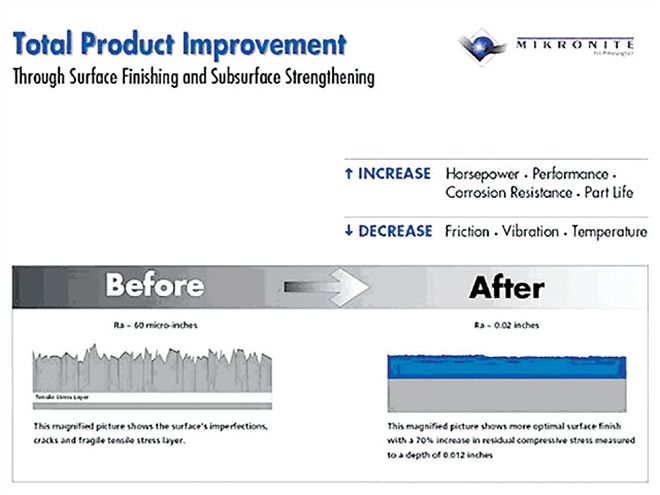

The point Mikronite Technologies stresses the most is that its process is not a coating, nor is it a temperature or chemical treatment. It is referred to as a "mechanical action process," and it could almost be thought of as a sort of hyper shot-peen, though where shot-peening blasts objects directly with relatively large pellets of steel, the Mikronite process uses much finer, lighter media applied with incredibly high force. The generation of that force is part of the proprietary aspect of the Mikronite process, though we probably wouldn't understand it even if the company did reveal the secret. What Mikronite Technologies will say is that centripetal force is one of the key elements to generating the intense pressure required to execute the process. The vague similarity to shot-peening is the resultant surface hardening, though parallels end there. Because the Mikronite process can be finely controlled, the quality and depth of the surface hardening are variable but also more uniform. In addition, the surface finish becomes amazingly smooth, as the process seems to perform a refined polishing function.

Demurjian explained that the media contact the item being treated in more of a sliding or lapping action, rather than as a direct impact. In this way, the media are still able to impart stress in the component's surface, but with more control. The lapping action also produces the highly refined surface that appears polished; the end result is the elimination of stress risers and microscopic voids without actually changing the dimensions of the component. By varying the media and the amount of force used during the process, the depth of treatment and degree of finish refinement can be controlled. Most of the media used are remarkably ordinary and often organic-walnut-shell fragments are a common selection. Demurjian pointed out that the media are usually mixed with different types of abrasives, "thus creating a completely dry, yet fluidized processing environment." It's the level of force generated that makes simple media perform the work of many times their densities; 25-70 g's is not unusual.

Despite the level of force, even delicate items can be subjected to the process, including ceramics and silicon chips. It's not surprising then to learn that this system was not developed specifically for automotive use. Heavy industry, aerospace, and even the medical field have thus far realized the benefits of the process; the car stuff happens to lend itself well, and the guys doing it dig racing. So do we, and after hearing the lengthy list of racing applications that had benefited from the Mikronite process, we wanted to see for ourselves.

Put To The Test

Given that rearend gears are subjected to lots of abuse in performance and race vehicles, ring-and-pinion sets are a prime beneficiary of Mikronite's treatment. The process should produce a stronger set of gears, thanks to the surface hardening, and the smooth finish should reduce friction at the mesh point. In theory, the gears should be able to endure more abuse while experiencing less wear over the long haul, but a more immediate benefit should be increased power to the wheels, since the improved gear-tooth finish will create less drag and therefore a reduced power draw.

We liked the purported benefits and the ease with which we could test them, and charting the performance before and after on a chassis dyno would be even easier. Our subject was a '93 Mustang 5.0 with the stock 8.8-inch rear axle, fitted with Ford Racing 3.55 gears. With a call to Year One, we had a new set of Ford Racing 3.55s off to Mikronite Technologies. Some might argue that the very same gearset should have been used, but we ordered a replacement set in the interest of time and not having yet another derelict car in the shop.

With the new gears in the mail, we took the Mustang to Westech Performance Group in Mira Loma, California, to get a baseline on the Superflow SF-790 chassis dyno. During discussions over this test, we'd also come up with an additional input to gauge before-and-after differences in the rearend assembly: gear-lube temperature. We figured that if friction was being reduced, lube temps should also see a reduction. The dyno system can handle numerous data inputs, so we rigged up a simple temperature probe to insert in the diff.

The rest of the test was straightforward; the Mustang was strapped down and plugged in, and the car was then "driven" on the dyno to bring fluid temps up to normal. Since we were monitoring the fluid temp, we wanted to make sure it was actually reaching typical levels, so the car was run at varying rpm and speed to simulate highway acceleration and deceleration. When the temps seemed to find their normal peaks, we made our pulls and found the horsepower peaks to be in the 204 range-about what we'd expect for a mostly stock 5.0.

The Results

When the new ring-and-pinion returned from Mikronite, everyone oohed and aahed when the box was opened; the typical dull-gray gearset we'd sent off returned looking as if it had been chromed. To the touch, the surface was so slick it felt almost as if it had a clear coating of some sort, but attempts to abrade any such layer turned up nothing. Besides, any coating would likely be stripped within the first few revolutions of the differential once installed.

Our cynicism at this point had been somewhat quelled, in part because we'd learned that the guys from our sister pub Muscle Mustangs & Fast Fords had recently done a similar test, and they'd also used an 8.8 Ford. Approaching with the same doubt we had, the MM&FF team had stamped an identifying code in the gears, disguised as part of the part number. Being in Jersey, they'd also taken it to Mikronite and watched as it went in and out of the machine. Their observations of the finished gears mimicked ours.

Next, we went to see Tim Moore for the gear swap. Moore is good with differentials and takes the time to make sure new gearsets mesh properly once installed. Our swap went swiftly, the only trouble being a slight increase in difficulty reading the wear-pattern compound due to the increased slickness.

We took time to put some leisurely highway miles on the new gears before testing and had 150 or so on the clock when we showed up at Westech for the retest. Back on the dyno, the Mustang was again cycled to stabilize fluid temps, and we were surprised to see they hadn't dropped-and, in some instances, seemed to be slightly higher. Admittedly, doing an absolute A-B comparison of fluid temps is difficult, but our cruise simulation and duration were matched reasonably well. After the pulls had been made, it did indeed appear that the treated gears were helping get more power to the rear wheels; a gain of 6 hp was realized with our testing.

The MM&FF guys saw an increase of about 7-8 hp during their test, and their car was an '05 that made more power, which means our numbers seemed to jibe. Word is trickling in from racers who claim this is a worthy upgrade; some of them have two years on their gears and can now realize the reduction in wear. Based on the evidence presented to us from a variety of sources and the fact that the treatment for a ring-and-pinion will set you back only about $200, we might tend to agree.