| Drag Racing With Nitrous - Armed And Dangerous - Wrenchin'

| Drag Racing With Nitrous - Armed And Dangerous - Wrenchin' Stop us if you've heard this one before: A wide-eyed, deep-pocketed newbie, eager to make his car as fast as possible in one swoop, drops a chunk of change on a nitrous kit (for all intents and purposes, the N2O could be substituted with a blower or turbo kit, too). He gets the thing installed and it works great for his regular commuter, so well that the owner is emboldened to see how the buggy stacks up against others in a more formal setting. To the drags he rolls, with tank of laughing gas in tow, only to either (A) get turned away by the track, because car and driver are not up to racing spec, or (B) get his ass handed to him over and over again because neither car nor driver are up to competitive snuff.

Laughing Gas and The ManBefore any novice even gets to the racetrack, he has to understand that most tracks and race sanctioning bodies consider a tank of nitrous oxide to be a dangerous thing. After all, the oxygenating gas is stored and transported in its liquid form under pressure in a heavy metal tank, also called a bottle.

Imagine the damage it could do if it was to sit unsecured in the cabin of an accelerating racecar. As such, there are a number of key safety points to keep in mind when planning a drag strip N2O setup.

The National Hot Rod Association and the NOPI Drag Racing Association, administrators of the two most visible sport compact drag racing series in the US, have comparable guidelines for implementing the funny stuff that depend mostly on competitor class.

In general, though, all bottles must be securely mounted, stamped with a U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) minimum 1,800-psi rating, and identified as nitrous oxide. Nitrous tank(s) mounted in the driver compartment need to be equipped with a relief valve that vents outside of the cabin. And thermostatically controlled blanket-type warmers are acceptable, but any other external heating of the bottle(s), such as flame heating, is prohibited.

The NHRA further mandates that all N2O systems and accessories used must be commercially available and installed per manufacturer's recommendations, we imagine to keep each system safe and consistent. Hoses running from bottle(s) to the solenoid must be high-pressure steel braided or of a similar NHRA-accepted variety.

Finally, drivers of sub-10-second cars on N2O in both leagues need to be dressed in the appropriate SFI-spec garb, namely 3.2A/15 standard pants and jacket and 3.3/5 standard gloves and shoes.

Class ActionsRegardless of engine setup, each sanctioning body's rulebook is one of the first things racers should get their hands on, if only to check which class would best suit driver and racecar. At the entry level both series' bracket classes require little more than a street-legal car, a drivers license, and an entry fee, with few limits on modifications or minimum weight. (For more on weight penalties and nitrous, see the sidebar.)

The next step up for NHRA competitors on nitrous is the Sport class, which is also for full-bodied, street-legal cars, just faster ones. The nearest NDRA equivalent for nitrous users is probably the Sportsman Turbo 4 street class. Vehicles are limited to two power adders, that is any pairing of nitrous oxide, blower, or turbo, and redundant adders, like multi-stage nitrous, are considered a single power adder. Drivers at this level oftentimes have to have a competition license, and the weight and chassis on the car may have to be certified.

The pinnacles for both series are the Pro classes, and both organizations split the fields between stock chassis and altered chassis vehicles. The NHRA's Hot Rod and NDRA's Pro Street Tire and Pro 4 Cylinder classes limit cars to an unaltered chassis and two power adders. For an altered chassis and up to two power adders, competitors will either need to sign up for the NHRA's Pro FWD or NDRA's Pro Outlaw designation, while NOPI Pro Compact contestants have similar chassis restrictions but no limits on power adders.

Nitrous for the 21st CenturyIn the nitrous basics article elsewhere in this issue, "Squeezin'," we briefly cover two different types of nitrous implementation, wet and dry systems. Modern systems, however, provide even more flexibility than that, and coupled with the right engine management, can make for a killer power adder. Herewith we examine the three basic types of systems, dry, wet, and direct port, and what racers do with them.

Direct port systems, sometimes called fogger systems, introduce nitrous and fuel directly into each intake port on an engine. These systems normally add N2O and fuel together through a fogger nozzle that mixes and meters the nitrous and fuel delivered to each cylinder.

It is widely believed that this is the most powerful and one of the most accurate forms of delivery, mainly because of the placement of each nozzle in each runner and the flexibility to use more and higher capacity solenoids.

A direct port setup usually has a distribution block and solenoid assembly that delivers nitrous and fuel to the nozzles. Because each cylinder has a specific nozzle and jetting for both nitrous and fuel, with some systems you can control the nitrous/fuel ratio for one cylinder without changing that of the others.

These systems are also one of the more complicated systems to install, as the intake has to be drilled, tapped, and the plumbing made to clear any existing obstructions. Because of this and the high output of these systems, they are most often used on racing vehicles.

"Anything over a 75-shot should be direct port," says Howard Anderson, owner and chief builder at AR Fabrication. AR Fab's claim to fame is that the shop has built a number of serious racecars, including an IDRC Quick class Civic hatch that ran a 10.8 in the quarter mile at 128 mph using only a Nitrous Express direct-port system for a power adder.

The shop is currently working on a top-secret '95 Civic coupe that will roll turbo B-series power, another direct port setup, and AEM's universal engine management.

Another purveyor of the laughing gas is Canadian Marc Kulak. He races, and built the ETD Racing '93 Civic Si hatchback that competes in the Pro Compact class in the Canadian Sport Compact Series. The designation permits two power adders, so the EG has a fully built single-cam D16Z6 motor outfitted with a GT40 turbo and a Zex direct port nitrous system.

The bottom end was prepared with Darton sleeves, Crower connecting rods, and custom Wiseco 9.4:1-compression pistons.

There's nothing especially fancy about the install (check the images), but Kulak is using an FJO Racing Products 341B stand-alone engine management system, which employs a progressive nitrous controller. Like multi-staged nitrous setups, which we'll discuss momentarily, a progressive controller can provide a gradual application of power. Kulak is pushing his Si in 2005 to be first Pro Compact D-series-powered car to make a quarter mile pass in the nines.

Dry IdeaRunning a dry nitrous system usually means the fuel required to make additional power with nitrous is going to be introduced through the fuel injectors. This keeps the upper intake dry of fuel, hence the expression "dry" system.

Upping fuel pressure is usually done in a couple different ways, either by increasing the pressure to the injectors by applying nitrous pressure from the solenoid assembly when the system is activated, or increasing the time the fuel injector stays on, which is probably easier and done through engine management.

In either case once the fuel has been added the nitrous can be introduced to burn the added fuel and generate more power.

Matt Patrick, Product Manager for Zex, used a dry kit in his '89 CRX Si drag racer, but as the second stage in a two-stage nitrous setup. Multi-staged systems generally incorporate multiple sets of nitrous and fuel solenoids so that power can be added at different times and at different levels, which some believe is better for creating a steady onset of power..

Theoretically the first stage should allow the vehicle to leave the starting line with a moderate boost; then when the drive train hooks up, another level of boost can be activated.

Off the line Patrick's turbocharged D16A6 engine would get a 125-shot with a Zex fogger kit first. Then depending on track conditions, the Fuel Air Spark Technology fuel enrichment unit would trigger another 125-shot, this time from a Zex dry kit, three or four seconds into the pass.

All the kits were off-the-shelf, and to ready the over-bored 1.6-liter powerplant for the increased stresses Patrick equipped it with Crower steel billet rods, SRP 9:1 slugs, and ARP head studs. Campaigned in NIRA and later the NDRA, the Zex CRX is no more, parted out and sold after the 2004 season.

Juicy JuiceThe third most common form of nitrous introduction are wet-style kits, systems that add nitrous and fuel together at the same time and place, normally three to four inches ahead of the throttle body. Because of where the mix enters the induction stream, this type of system will typically make the upper intake wet with fuel. Some believe these systems are best used with turbo/supercharged applications.

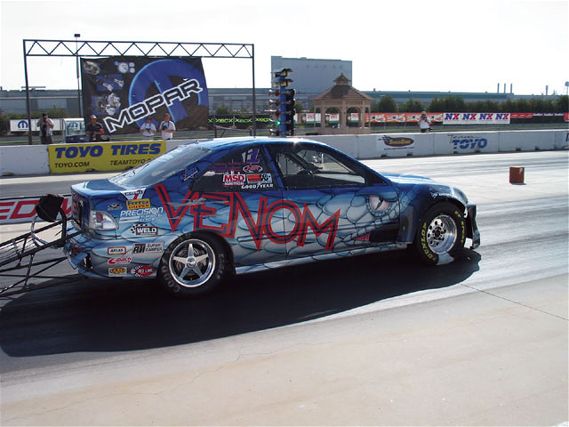

NDRA Pro 4-Cylinder pilot Chuck Seitsinger runs a Nitrous Express wet kit in the Alternative Motorsports '92 Civic hatchback. The turbocharged B18 under the hood has been opened up to 1.9 liters and outfitted with Golden Eagle sleeves, Manley rods, CP pistons, and Motec engine management.

Currently the NX kit is delivering a 100-shot, but so much horsepower is being pushed to the wheels that the stock Honda gearboxes are breaking for Seitsinger.

"I really need an XTRAC gearbox, but right now we just don't have the money," he laments. "For now we're having to detune the car." Still, with a stepped down motor, the hatch is capable of running 8.50- and 8.60-second runs.

Open to InterpretationWhile there are plenty of examples in the race world to emulate as far as N2O application, racecar builders pretty much have to stick to conventional types of installations per sanctioning body guidelines. Outside the influence of a rulebook, however, some have been able to come up with some highly nuanced ways to squeeze.

Hasport kingpin Brian Gillespie runs a single-stage NX wet system as a dry one in his H22 CRX commuter car. The system uses a single dry system nozzle from a different manufacturer placed as far away from the throttle body in the intake tube as possible to take advantage of the cooling effects of the nitrous.

The improvised kit appears to be quite effective, too; hooking up an NX 45-shot jet in the nozzle made a true 45-horsepower increase in power according to the Dynapack dyno at Church Automotive Testing.

Why'd Gillespie do this? Mainly because he didn't want to have to worry about dealing with fluctuating fuel pressures. Apparently with the Hondata S200 engine management he just needs to install a bigger set of injectors and the ECU will adjust fuel pressure accordingly.

Gillespie is also working on a three-stage nitrous system for Hasport's supercharged K24-powered CRX for the Ultimate Street Car Challenge. Using AEM management and smaller first-stage and larger second-stage jetting, Hasport hopes to design the system so both nozzles first fire individually for stages one and two, then together, which would be the third stage.

Words on weightWhile bracket classes are easiest to get into, it's the other designations that truly provide challenge at the drags. Part of meeting that challenge is boning up on the weight penalties incurred for using nitrous, our power adder of choice. Keep in mind that weight is measured with the driver in the car after the race.

The NDRA has no minimum vehicle weight limit for its Sportsman classes, but the NHRA expects its Sport class competitors to weigh 2,400 pounds if they have one power adder, and 100 pounds more if they have two.

Unless you have six cylinders, there appears to be no minimum weight for NDRA Pro Street Tire guys, but racers in Pro 4 Cylinder are either 0.8 pounds for every cubic centimeter of displacement or at least 1,800 pounds.

The NHRA employs a similar formula that assigns weight based on displacement, the number of power adders, and whether or not an OEM gearbox is used, with 1,800 pounds also at its low end.

Lastly, NHRA Pro front-drive participants must make their cars 1,750 pounds each if they have one power adder, or 1,850 pounds if they're using two. NOPI's Pro Outlaw class requires at least 1,600 pounds between car and driver, and its Pro Compact category demands 0.7 pounds per CC of displacement, with a minimum weight of 1,750 pounds