Few off-roaders will argue with the advantages a Q-jet carb has over every other type of carburetor. The float-bowl design limits the effects that tilty or bouncy trails have on the way the engine runs, and the small primaries on a Q-jet provide crisp throttle response and respectable fuel economy. However, many 'wheelers feel a Q-jet has no place on a modified engine.

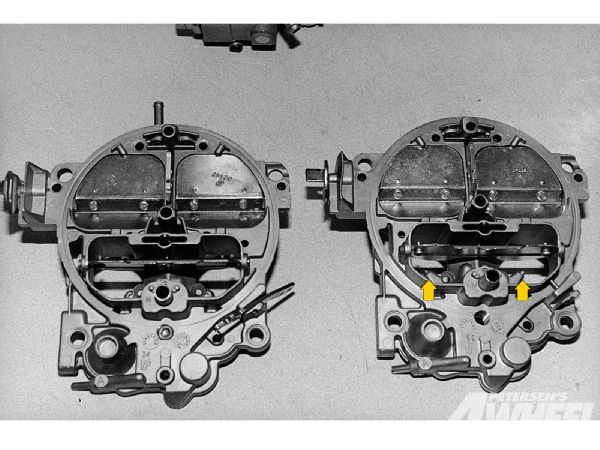

Sean Murphy at Jones Performance Fuel Systems loves building Q-jets for high-performance engines because most people don't think it can be done. He uses Q-jets originally built for trucks (right) since these have extra air bleeds (arrows) that lean the mixture under normal steady load for better throttle response and economy. These carbs are rated at 800 cfm as opposed to 750 cfm for car units.

Sean Murphy at Jones Performance Fuel Systems loves building Q-jets for high-performance engines because most people don't think it can be done. He uses Q-jets originally built for trucks (right) since these have extra air bleeds (arrows) that lean the mixture under normal steady load for better throttle response and economy. These carbs are rated at 800 cfm as opposed to 750 cfm for car units.

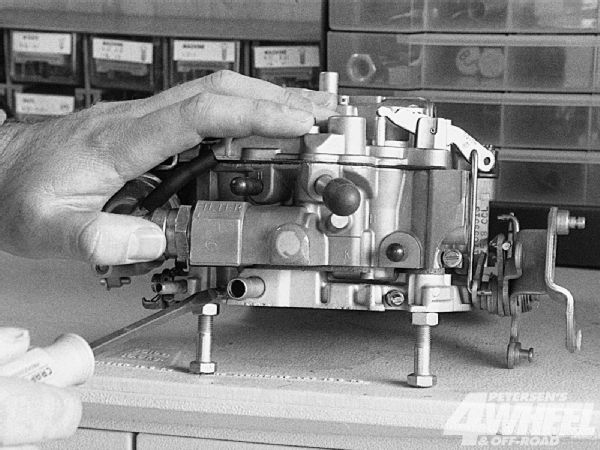

With the help of Sean Murphy at Jones Performance Fuel Systems, we're here to dispel that myth. Jones builds all kinds of carbs for every conceivable application, ranging from stock four-cylinders to 1,000hp big-blocks, and Murphy says it's not a problem to build a Q-jet to work on a modified street and off-road engine.

To make the appropriate modifications, Jones needs accurate information about the engine and vehicle usage. The first thing Murphy did was ask us details about our engine. The mill is a 350 Chevy with flat-top pistons, stock 487X casting number heads, 2.02-inch intake and 1.60-inch exhaust valves, a Lunati hydraulic cam with 228 degrees of duration at 0.050-inch lift (275 degrees advertised) and 0.478-inch lift, an ACCEL HEI distributor, 1 3/4-inch primary tube headers with 2 1/2-inch dual exhaust, and an Edelbrock Performer RPM manifold. The engine block and heads were machined to bring the compression up to 9.8:1. The engine produced 364 hp at 5,500 rpm and 396 lb-ft of torque at 4,000. That's roughly twice the power produced by many mid-'70s engines of the same size, so the fuel-mixing requirements for this engine are significantly different from a stock engine.

Murphy said the most common problems encountered when using a Q-jet on a modified engine result from a low vacuum signal at the carburetor, which causes it to draw in less air and fuel. This condition is caused by using a larger-than-stock camshaft and makes the carburetor react sluggishly. Therefore, most of Murphy's modifications were to circuits that feed fuel to the engine at or just off idle. He also offered us tips on tuning the rest of the carburetor with traditional jets and metering rods.

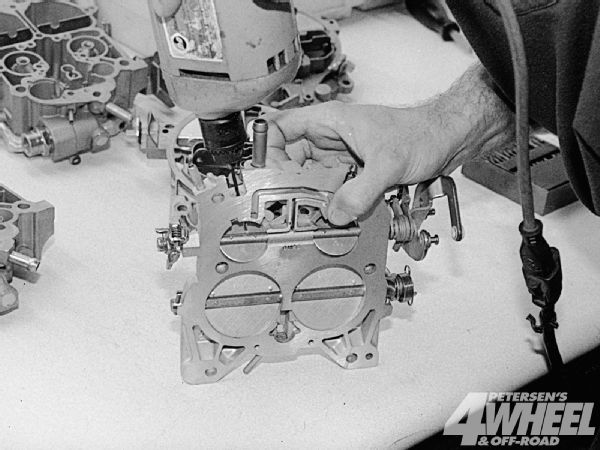

Truck engines with larger-than-stock cams generally give the carb less vacuum signal and therefore don't draw as much air and fuel through the carb at idle and low-throttle opening. If the mixture screws are threaded out too far and the engine still won't idle correctly, this is probably the case with your engine. To cure this, Murphy first enlarged the idle feed holes in the baseplate that provide air at idle.

Truck engines with larger-than-stock cams generally give the carb less vacuum signal and therefore don't draw as much air and fuel through the carb at idle and low-throttle opening. If the mixture screws are threaded out too far and the engine still won't idle correctly, this is probably the case with your engine. To cure this, Murphy first enlarged the idle feed holes in the baseplate that provide air at idle.

Tuning Tips

For all its advantages, the Q-jet carburetor has one downfall: it can be challenging to tune for smooth, bog-free acceleration. To help you avoid name calling, here are the tuning tips Jones Performance Fuel Systems gave us. They're in the order you should follow when adjusting your carb and should result in a smooth-running unit. If you try everything twice and are still plagued by problems, inspect the timing curve of the ignition and consider whether you really have the proper-size carb for your application. These two points are often overlooked and cause more problems than carb tuning can cure.

Start with the idle mixture screws four turns out from the bottomed position. As you adjust the screws, look for the highest vacuum reading. You may need to readjust these as you make other changes to the carb and ignition timing.

PhotosView Slideshow

Start with the idle mixture screws four turns out from the bottomed position. As you adjust the screws, look for the highest vacuum reading. You may need to readjust these as you make other changes to the carb and ignition timing.

PhotosView Slideshow