Any fool can pick up a hammer and bend a piece of metal, but it takes an artist to finesse a quarter-panel out of a flat 4x8 sheet of cold rolled steel. The same can be said for those in the business of paint removal. There are those who do more damage than good because they don’t know what (or why) they’re doing, and there are those who understand the science of it all—someone like Patrick McConaghie, owner of Pro-Strip Media Blasting in Mesa, Arizona.

Though only 38 years old, Patrick McConaghie (the owner of Pro-Strip Media Blasting) has been in the blasting business for 16 years, and has acquired some useful knowledge on the best way to get paint off metal surfaces.

Though only 38 years old, Patrick McConaghie (the owner of Pro-Strip Media Blasting) has been in the blasting business for 16 years, and has acquired some useful knowledge on the best way to get paint off metal surfaces.

At 38 years of age, McConaghie has nearly spent his entire adult life figuring out the best way to remove paint from metal. Part of his education has been through trial and error but, in one instance, it was a customer (who worked in the aerospace industry) who gave him insight into what actually happens to metal when it gets blasted.

The customer told him about Almen strips, which are used in aerospace to determine how much shot peening a particular piece of metal can take before it bends. It relates to the blasting process because, as McConaghie explains it, each little particle of blasting material (whether it be glass bead, aluminum oxide, copper slag, or any other abrasive material) is like the head of a tiny hammer. Everyone knows what happens when you strike a flat piece of metal with a hammer, but the same thing happens on an infinitesimal level with media particles being shot out of a blasting gun at a high rate of pressure. Leave a blasting gun in one spot too long and what happens? It bends or, employing the phrase used more commonly in the blasting community, warps.

McConaghie uses low pressure and a 30-degree angle to the item so as to not damage it. Using the gun at low pressure also means it’s a slow-going process, but the metal won’t get damaged.

McConaghie uses low pressure and a 30-degree angle to the item so as to not damage it. Using the gun at low pressure also means it’s a slow-going process, but the metal won’t get damaged.

McConaghie believes it’s not heat that is responsible for warping metal, it’s the miniature shot peening that is going on: tens of thousands to millions of repeated tiny hammer blows. What McConaghie points to can be tested this way: After intentionally warping a car part, check the temperature of the warped area with your bare hand. It should be cool to the touch but distorted. Now think of metal objects put in a 500-degree oven before being powdercoated—they don’t warp. So the question is: What compels people to think bead blasting will generate a high enough temperature (i.e. higher than a powdercoating oven) to warp metal? You need to get up to welding-level temperatures before you can start to warp metal from heat alone. Another thought is backed up by recognizing the pieces most associated with being warped: hoods, trunklids, doorskins—all of which have large flat surfaces. Now, what shapes are the easiest to produce a dent when hit with a hammer, a large flat piece of metal or something with a curve or peak?

Here’s what we have to start with: a stock ’34 Ford five-window. Luckily there aren’t too many coats of primer or paint to deal with.

Here’s what we have to start with: a stock ’34 Ford five-window. Luckily there aren’t too many coats of primer or paint to deal with.

McConaghie considers himself lucky because, after dropping off parts a few times at a company that did blasting its owner asked him if he wanted to buy the business. He accepted the challenge, and moved it 15 years ago from Apache Junction to Mesa. Since then his main focus has been classic cars, but smaller odd jobs still come into the shop when he has the time (which is not often). He uses an overhead hoist to access the bottom of cars, and he can strip three or four cars a week. Half of those cars are owned by hobbyists, the other half being business owners who restore or customize cars for a living. He also strips a lot of muscle cars, Model As, ’50-era Chevys and trucks, and, once, a $1.5 million Maserati (he had to do it in one day because the owner didn’t want to leave it anywhere overnight!).

From what McConaghie sees, most folks don’t realize what is under their paint. They may believe one thing or, sometimes, were told one thing, but McConaghie has the unpleasant task of informing them their ride isn’t as pristine as they thought it was. But it’s part of the service he gives, which also includes cleaning parts, blowing the media out of the cracks and crevasses (a lot of shops don’t do that), and even vacuuming out the car.

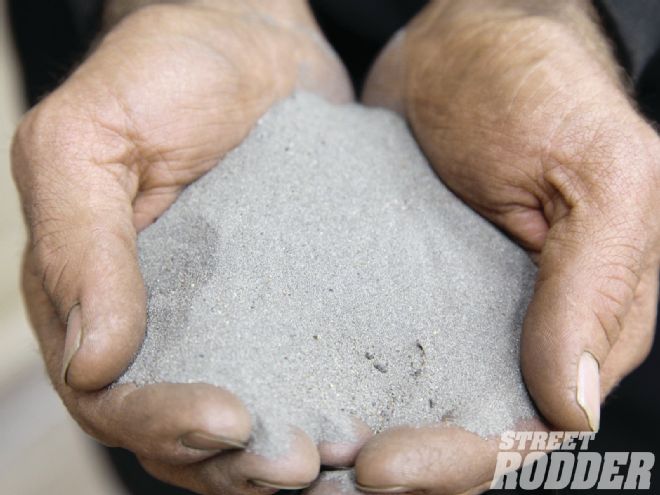

Pro-Strip also uses various medias for stripping, depending on what the surface material is, and there are almost as many types of blasting media out there as there are people who use it. Some media is bio-degradable, some will remove everything (including Bondo), and some that will take paint off but not remove any rust. Pro-Strip uses plastic media or walnut shell on aluminum, or a copper slag and garnet mix for more aggressive work on steel. They also use walnut shell and a homemade mix of aluminum oxide and # 10-glass bead, which is similar to 120-grit sandpaper. For someone working in their home shop, even playground sand (like you can purchase at Home Depot) can be used for stripping as it’s very coarse, though McConaghie doesn’t recommend it for sheetmetal as he feels it’s too aggressive. Soda media is sometimes used for some aluminum or fiberglass bodies, and McConaghie is aware of some myths surrounding soda blasting, too (such as paint not sticking to the metal after the blast job). He believes it’s simply because the residue from the soda media hadn’t been properly neutralized and cleaned off the surface before the paint material was applied.

Pro-Strip uses three grades of media material (coarse, medium, soft) depending on how aggressive they want to be with the part being blasted. The material used on this project is a homemade blend of aluminum oxide, glass bead, and walnut shell.

Pro-Strip uses three grades of media material (coarse, medium, soft) depending on how aggressive they want to be with the part being blasted. The material used on this project is a homemade blend of aluminum oxide, glass bead, and walnut shell.

McConaghie approaches paint stripping a little different than most, too, in that he likes to take one layer of paint off at a time per each section. He realizes it takes longer to do, but he says it’s a balance between speed and safety. He also operates the blast gun at a low psi, and then aims it at a roughly 30 degrees to the product (which will lift the material off the surface much like a putty knife would). Varying the distance from the surface also helps control the blasting process, too.

If there is more than one layer of paint to cut through, McConaghie will take only one layer off at a time.

If there is more than one layer of paint to cut through, McConaghie will take only one layer off at a time.

Though he believes every classic car has some rust somewhere, McConaghie’s goal is to do a job that allows the owner/builder to work with a surface that is smooth and that might need only a scuff before primer is applied. And, as anyone who has built a car knows, not having to worry what you get back from the media blaster is a great thing, and something Pro-Strip strives to do with each job.

We were lucky: the only amount of rust damage on the entire car were some small pinholes at the back of the driver rear fenderwell.

We were lucky: the only amount of rust damage on the entire car were some small pinholes at the back of the driver rear fenderwell.

The approach on how each piece is blasted is different for each piece, depending on how much flat surface it has, but the result is the same. The ashtray cover or grille apron is easier to do than the inside and outside of a door.

The approach on how each piece is blasted is different for each piece, depending on how much flat surface it has, but the result is the same. The ashtray cover or grille apron is easier to do than the inside and outside of a door.

After it rolls out of Pro-Strip’s booth with no damage or surprises, the finished product is now ready to be prepped for primer and paint.

After it rolls out of Pro-Strip’s booth with no damage or surprises, the finished product is now ready to be prepped for primer and paint.