Author’s note: In the Jan. ’09 issue of HPP, the technical article “Keep a Cool Head” described installing Evans NPG coolant in a Pontiac engine, along with other modifications. Due to the varied subject matter in that primer, HPP did not have the space to fully expose the theoretical aspect of heat transfer in a Pontiac engine and how that is altered with the Evans product. This primer picks up where we left off in 2009.

Many things have changed in the Pontiac world over the years. Components that were considered essential have been replaced with new technologies. The carburetor succumbed to the fuel injector; breaker points first to electronic ignition and eventually a system that has eliminated the distributor; and the simple throttle cable gave way to drive-by-wire technology. But little thought has been given to the heat transfer from the water jacket of the Pontiac cylinder head to the liquid coolant. This is what is required to keep an engine cool and detonation free, especially in a high-performance application or extreme use; that is until Evans Cooling Systems completely rethought the chemistry of cooling an engine.

Before this engine-coolant advanced concept that employs no water can be understood as it relates to a Pontiac, a review of cooling-system basics is in order.

The temperature rating of a thermostat is when it just cracks open and flow begins. It then requires between a 10 and 20 degrees F rise in liquid temperature to be fully open.

The temperature rating of a thermostat is when it just cracks open and flow begins. It then requires between a 10 and 20 degrees F rise in liquid temperature to be fully open.

It is going to be hard for many Pontiac people to accept that fact that engine coolant on the verge of boiling is a good and proper thing. The caveat? It needs to occur in the cylinder head and not in the radiator.

The dreaded engine boil-over that strands you on the side of the road with the hood open and a cloud of steam emanating from the radiator is usually what comes to mind. That kind of boiling is not good.

When radiator boil-over occurs, it is rooted in the coolant becoming super heated and the radiator’s inability to transfer enough BTU of heat into the air. (This is known as rejection.) If this occurs, the coolant starts to boil and expand just as a pot of water would on a kitchen stove.

It is imperative to understand that the liquid’s job is to cool the engine, and the function of the radiator is to cool the liquid. As the liquid passes through the radiator, its temperature drops so that it can be an effective heat-absorption medium when it is pumped back through the engine. The liquid’s time in the radiator can be considered rest and relaxation as a soldier would receive between combat assignments.

Evans produces a high-flow and extremely efficient Pontiac water pump that employs a scroll-style impeller. It can be used with traditional water-based coolant or NPG.

Evans produces a high-flow and extremely efficient Pontiac water pump that employs a scroll-style impeller. It can be used with traditional water-based coolant or NPG.

If the liquid is not provided the opportunity to drop in temperature during its residence in the radiator, it then possesses too much heat to be effective. The liquid will keep absorbing heat from the engine until it can take no more. At that time, it boils and changes phase from a liquid to a gaseous form. The chemical composition of the liquid along with the operating pressure of the cooling system all impact the temperature at which the phase change occurs but cannot stop it. When the coolant boils and becomes a vapor, it is ineffective in pulling heat from the cylinder head.

The introduction of the radiator pressure cap by General Motors in the ’30s, along with the adoption of glycol-based coolants, were major advancements in raising the boiling temperature of coolant. As an aside, for every one pound of pressure that is added to a cooling system through a pressure cap, the boiling point increases 3 degrees F.

Environmental factors impact the boiling point of the coolant, also. Altitude has a major influence on lowering the boiling point of a liquid since there is less atmospheric pressure on it.

Misunderstanding the purpose of liquid coolant is rooted in the fact that the industry monitors the coolant temperature alone and not in conjunction with the metal-surface temperature of the combustion chamber in the cylinder head. Think of it as a mariner receiving directions in latitude without longitude. The proper method to determine if the engine is in thermal distress is to compare the liquid temperature to the metal-surface temperature of the cylinder head. Only then can the picture be clear. If the metal-surface temperature is climbing and the liquid reading is not keeping up, then the engine is on the verge of metal overheating though the coolant may be far from boiling.

As the liquid’s temperature increases its storage ability, its potential to absorb more heat is diminished. When this occurs, the liquid temperature as read on a coolant gauge may appear to be stable, albeit at an elevated temperature, but the metal-surface temperature of the combustion chamber and around the exhaust valve skyrockets. This can lead to detonation (ping) and engine failure from a cracked cylinder head.

Every Pontiac engine can reap a benefit from the Evans NPG coolant.

Every Pontiac engine can reap a benefit from the Evans NPG coolant.

Engines that employ an aluminum cylinder head are extremely sensitive to this since the steel valve seats are pressed into the head as an insert. Numerous or prolonged excursions to extreme metal temperatures along with thermal cycling can cause the seat to fall out. With rare exception, this is met with total destruction of the engine as the piston collides with the valve and the steel seat.

In almost every case, the engine never overheated according to the liquid temperature but the metal surfaces did. Thus, the most effective liquid coolant is one that has the ability to absorb a high amount of heat before boiling, which will result in the coolest metal temperatures in the cylinder head. When the liquid can abstain from boiling and continue to absorb heat there will be more thermal transfer from the cylinder head.

When discussing a cooling system it must be noted that though the coolant is also employed to remove heat from the engine block and cylinder walls, its most challenging assignment is to control the temperature of the combustion chamber and exhaust-valve area.

When converting from water-based coolant for an engine that is in use, a refractometer is employed to determine moisture content. With an engine rebuild, the Evans is a direct pour-in other than blowing out the heater core.

When converting from water-based coolant for an engine that is in use, a refractometer is employed to determine moisture content. With an engine rebuild, the Evans is a direct pour-in other than blowing out the heater core.

The load and thus the heat rejection into the liquid coolant of an engine are not linear. It is dependent on many factors. Given a specific engine, the heat rejection required will depend on the operating state of the vehicle.

A Pontiac that is used for light-load driving (even if it is a great distance) will not put much heat into the coolant. This is due to the engine not being required to produce much power for the driving state. The amount of fuel consumed and the volumetric efficiency of the cylinder bore are low. If the same Pontiac is now required to climb a steep hill or pull a trailer, then the load on the liquid coolant increases dramatically. This is the reason that since the days of the early automobile, car companies have performed hot-weather testing in the American west where a combination of high ambient temperatures and extreme elevation can be found at the same time.

Turbulent flow through the cooling system is necessary for the most effective thermal transfer. This action will cause a churning and allow the coolant to absorb more heat from the components it comes in contact with.

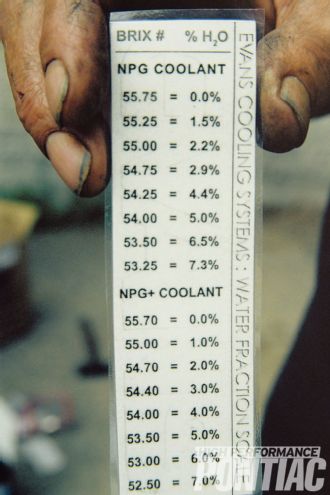

The refractometer reads in a Brix scale. A chart is then used to determine residual water content. A value of 5 percent or less is acceptable.

The refractometer reads in a Brix scale. A chart is then used to determine residual water content. A value of 5 percent or less is acceptable.

In like fashion it is imperative that the cooling system is devoid of any air bubbles and is a solid stream of liquid. Air is a very poor heat-transfer agent when compared to a liquid. If the cooling system is air bound then the areas that do not have liquid contacting them very quickly become superheated, and that will result in extreme thermal stress.

The liquid coolant goes through a number of defined boiling stages as it absorbs heat and prior to becoming steam. These range from nucleate boiling to crisis boiling. When the liquid is just on the verge of entering the nucleate stage is when the most heat transfer occurs. When crisis boiling occurs, the liquid for all intents and purposes does little to cool the cylinder head and the metal-surface temperature rises rapidly.

The key to proper heat transfer is to allow the coolant to just enter the nucleate stage when the engine is under severe or heavy load. Then have the system pressure move the boiling coolant away from the site, taking the heat along with it, and recondense back to a liquid as it is pushed away. This cycle of heating, nucleate boiling, release from the site, and recondensing goes on continually in the cylinder heads’ water jackets and is responsible for the consumption of the chemical-additive package that is included in traditional engine coolant. This is why anti-freeze wears out and needs to be changed.

Products that are designed as an engine coolant include anti-corrosion inhibitors along with elements to make it more slippery. This is represented using a metric of dymes/centimeter. It is a measure of the surface tension of the coolant. The lower the surface tension the liquid has, the easier it will release from the water jacket casting in the cylinder when nucleate boiling occurs. It can then recondense and remove the necessary heat. A liquid that likes to cling may have the ability to absorb heat but will negate that benefit by refusing to leave the nucleate boiling site. It will then enter crisis boiling and become worthless as a coolant.

For many years it was believed that water was the best engine coolant since it has a specific heat rating of one, but it is a poor choice. Even if you do not consider the corrosion it causes, the low boiling point even when used with a radiator cap, and the high surface tension means that it will not do an effective job of removing heat from the cylinder head when compared to an application-specific engine coolant, no matter what the dashboard gauge states.

The cooling system is bled in a conventional manner with the Evans NPG-C, as would be done with a water-based coolant.

The cooling system is bled in a conventional manner with the Evans NPG-C, as would be done with a water-based coolant.

While other areas of engine technology have dramatically improved in the last decade, engine coolant (usually a mixture of ethylene glycol and water in a 50/50 solution) has remained the standard. There is no denying that traditional water-based coolant worked—there are not cars overheated all over the road—but a better chemistry was needed for engines to become more efficient and to address environmental concerns.

Here’s the analogy: The old bias-ply tire held air and got the vehicle down the road, but it cannot be compared to the performance, wear, and overall improvement of a modern radial. Just think of the Evans NPG-C coolant as a modern radial tire and traditional water-based anti-freeze as a bias-ply design.

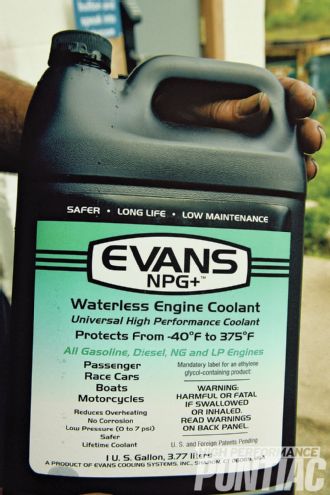

Evans NPG-C gets it name from being a non-aqueous glycol that has no water mixed with it. A side benefit of the elimination of the water from the chemistry means that corrosion and cavitation in the cooling system and engine is completely eliminated, and there are no additives that deplete. The Evans NPG-C is a lifetime coolant.

The real benefit of this modern chemistry is that it does not boil until 375 degrees F, virtually eliminating any chance of overheating in the radiator. This high boiling point is responsible for a drastic drop in the metal-surface temperature of the combustion chamber in the cylinder head over traditional water-based coolant. Since it will refrain from boiling, more heat transfer occurs.

Once the coolant enters the nucleate stage, the fact that it has a much lower surface tension as measured in dynes/centimeter (it is more slippery) means it releases from the water jacket with less system pressure and allows fresh coolant to come in contact with the region. Thanks to Evans NPG-C unique chemistry, the system operating pressure is lower since it does not expand at the same rate as conventional coolants nor does it ever freeze. All of these attributes allow for a more aggressive fuel mixture and ignition curve (or boost pressure) since heat-induced detonation will be eliminated in performance use.

When Evans NPG-C is employed in a passenger car or heavy-duty application, it will promote increased longevity for the engine and its components, the ability to use lower octane fuel, and reduced maintenance costs.

To convert from traditional coolant to the Evans NPG-C, all that is required is the complete removal of the old coolant and a refill with the Evans product. The Evans website goes over the procedure in great detail.

For those who want the most from their engines, it is this author’s opinion that the choice is clear. Get the water out and pour in the Evans!