Q:

Jose Cervantes Asks…

I’m looking into upgrading my ’81 Oldsmobile Calais with a 4.3L (260ci) V8. Are there aftermarket parts for this engine, including headers, chrome valve covers, dual-exhaust systems, intake manifolds, carburetors, a dual-snorkel air filter, and any other performance parts? I’ve been told to just dump the engine; everyone says it’s not worth hopping up.

I’m not gonna pull any punches here: The little-bitty 260 Olds isn’t worth hopping up. Size matters. Although a member of the Olds small-block V8 family, the 260’s tiny 3.5-inch bore pretty much precludes a head swap from a 350-or-larger Olds engine or using modern aftermarket heads, such as Edelbrock’s offerings.

Ditto for an intake manifold swap. All 260s came stock with two-barrel carbs. There are no dedicated factory or aftermarket 260 four-barrel intakes. Intakes intended for larger Olds small-blocks physically bolt on to a 260, but there is a significant port mismatch between the four-barrel intake’s runner exits and the 260’s peanut-sized intake ports, leading to reversion and poor fuel distribution. Yes, there are workarounds (I’ll get to that below), but since complete 307, 330, 350, and even 403 Olds small-blocks are direct bolt-ins for a 260 (they all have the same external dimensions), why spend any money hopping up a 260 when even a stock larger-displacement Olds will run rings around it?

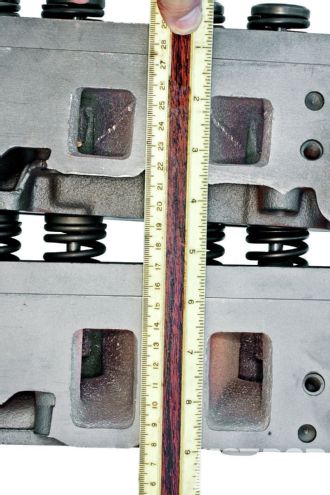

Here’s why no stock or aftermarket four-barrel Olds intake is a good fit on a 260: Its teeny-tiny 13⁄8 x 15⁄16-inch intake ports (top) are not even half that of a typical 307 head with its 2-inch–tall runners (bottom). 350 and 403 heads runners are slightly larger yet.

Here’s why no stock or aftermarket four-barrel Olds intake is a good fit on a 260: Its teeny-tiny 13⁄8 x 15⁄16-inch intake ports (top) are not even half that of a typical 307 head with its 2-inch–tall runners (bottom). 350 and 403 heads runners are slightly larger yet.

And don’t forget a big-block Olds (400, 425, or 455). They’ll also bolt-up to your existing mounts and transmission, but due to the big-blocks’ higher deck-height, some of the existing small-block front accessory brackets may not work. Depending on the intake manifold, hood clearance might be a problem with a big-block as well.

Not that your existing TH200 trans will last long behind a big-block Olds. In fact, it probably won’t last long behind a 350 or 403, either. So, if going the larger engine route, grab a takeout motor plus the trans bolted up behind it. Depending on which trans you end up with, that could require driveshaft and crossmember mods. Advanced Resources (GForce) offers G-body double-hump crossmembers suitable for a variety of transmissions, which also have plenty of clearance for that true dual-exhaust system you want. TA Performance is one source for G-body dual-exhaust systems.

OK, so you’re bound and determined to ignore my sage advice and hop up your pipsqueak engine anyway: What 260 parts interchange with other Olds engines? The following parts are physically interchangeable among all “modern” Olds V8 engines: most flexplates and flywheels (’67-and-earlier have a slightly different bolt pattern than ’68-and-later; they must match the crank), engine mounts, oil pan, front cover, water pump (snout lengths vary), bellhousing (also interchanges with modern Buick, Cadillac, and Pontiac), oil pump, oil pump driveshaft, rocker arms and fulcrums (except early 330 with a shaft-mounted valvetrain), cam and lifters (except for different lifter bank angles and lifter diameters used in some years; plus late factory roller-cam blocks are machined for stock-style retention “spiders”), harmonic balancer, cam bearings, timing chains, timing gears, starters, ’68-and-later distributors, and exhaust manifolds or headers (but the rare late 307 high-swirl heads’ were round or D-shaped, not rectangular like all the others; port profiles should match).

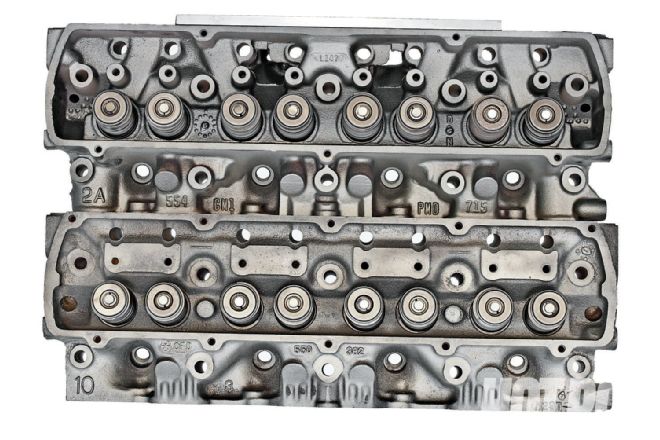

The exhaust side of the ’77–’81 260 head (ID 2A, top) is similar to nearly all Olds heads; like them, it lacks a full-length divider between the center ports, degrading the performance of tuned-length headers. One of the few that actually do have a full divider is the ’75–’76 early 260 head (ID 10/casting 550362, bottom)—unfortunately it still has “peanut”-sized intakes.

The exhaust side of the ’77–’81 260 head (ID 2A, top) is similar to nearly all Olds heads; like them, it lacks a full-length divider between the center ports, degrading the performance of tuned-length headers. One of the few that actually do have a full divider is the ’75–’76 early 260 head (ID 10/casting 550362, bottom)—unfortunately it still has “peanut”-sized intakes.

Small-block Olds stock cranks interchange (with the caveat about early/late flywheel bolt-patterns). All stock Olds small-block cranks have the same 3.385-inch stroke (displacement varies solely by changing the cylinder-bore diameter). 330 cranks were forged (good luck finding one). All ’68–’72 350 cranks and some ’73–’75 350 cranks were cast nodular iron. Other small-block Olds cranks were only gray iron. Nodular-iron small-block Olds cranks are said to support about 600 peak hp; gray-iron cranks, about 400 hp. Nodular-iron cranks have a large “N” or “NA” cast into the No. 1 counterweight.

Not all cranks are drilled for a manual-trans pilot-bearing. Dick Miller offers an adapter bearing (PN DMR-5022) that converts a Chevy, Pontiac, Buick, Cadillac, or Oldsmobile crank from an automatic transmission crank to a standard shift transmission crank without the need to modify the crank itself. Install with red thread-locker where the torque converter snout would normally ride, then cut approximately 1⁄8 inch off the tip of the manual transmission’s input shaft (you can do this in the field with a hacksaw if desperate). Miller says his system also provides greater support to the input shaft because “the bearing is closer to the transmission.”

260 2A 307 5A 350 3A The ’77–’81 260 head (ID 2A/casting No. 554715) had 57cc chambers, 1.522/1.300-inch valves, and 2-inch spacing between chambers; ’80–’85 307 ID 5A/casting 3317 had 1.750/1.500 valves, 67cc chambers, and 13⁄16-inch spacing (it can serve as a 260 upgrade); common late-’70s 350 ID 3A/casting 554716 had 1.875/1.500 valves, 75cc chambers, and only 9⁄16-inch spacing (it and similar heads won’t work on a 260).

260 2A 307 5A 350 3A The ’77–’81 260 head (ID 2A/casting No. 554715) had 57cc chambers, 1.522/1.300-inch valves, and 2-inch spacing between chambers; ’80–’85 307 ID 5A/casting 3317 had 1.750/1.500 valves, 67cc chambers, and 13⁄16-inch spacing (it can serve as a 260 upgrade); common late-’70s 350 ID 3A/casting 554716 had 1.875/1.500 valves, 75cc chambers, and only 9⁄16-inch spacing (it and similar heads won’t work on a 260).

Heads basically interchange, except manifold ports may not align as previously noted. Earlier heads set up for 7⁄16-inch head-bolts need to have their head-bolt holes drilled out to ½ inch for use on those later blocks requiring ½-inch bolts. Also, as applied to the small-bore 260 specifically, big-valve heads from 350-or-larger engines will almost certainly contact the cylinder wall. Although 307 heads may work with bore-notching, most Olds experts claim the gains are minimal because of valve-shrouding effects.

Nevertheless, some stubborn Olds 260 hot rodders report successfully installing ’80–’85 307 “5A” heads on a 260. Many Olds guys ID Olds small-block heads by the large, “shorthand” number or number and letter cast on the end of the head’s exhaust-side (big-block heads have ID letters only). However, Cylinder Head Exchange points out that some completely different heads have the same ID letter, so it really wants to know the casting No, also usually located on the exhaust-side above the runner roofs (“3317” in the case of the 307 5A head). Check out the comparison and identification photos on these pages; they were shot at the Cylinder Head Exchange, which specializes in stocking head cores for just about every domestic and foreign engine.

The ’76-and-earlier Olds V8s use 10-bolt valve covers, as on this ID 10 260 head (bottom). All ‘77–’90 Olds 260-403 V8s have five-hole covers (ID 2A 260 shown, top). Earlier 10-hole versions fit; just use RTV in the extra holes to prevent leaks.

The ’76-and-earlier Olds V8s use 10-bolt valve covers, as on this ID 10 260 head (bottom). All ‘77–’90 Olds 260-403 V8s have five-hole covers (ID 2A 260 shown, top). Earlier 10-hole versions fit; just use RTV in the extra holes to prevent leaks.

The 307 heads have 1.750-inch intake/1.500-inch exhaust valves, compared to a 260’s 1.522/1.300-inch valve-combo. With any sort of performance cam you must check valve-to-piston clearance and be prepared to machine the piston valve-notches as required. Ditto for checking the valve-to-cylinder bore clearance, and notching the bores as needed. Use 307 intake gaskets to avoid port-overhang; use 307 head gaskets to avoid combustion-chamber overlap.

Another downside is that the 307 heads’ combustion chambers are about 10cc larger than the 260 combustion-chambers, resulting in the 260’s abysmally-low 7.85:1 real-world compression-ratio dropping at least another half-point. Milling the new heads 0.030–0.040-inch will restore compression, such as it is. Another solution (particularly if the engine needs rebuilding anyway) is pop-up pistons to get at least 9.5:1 compression, but for the oddball 260 they’d have to be custom-made. You can bore a 260 0.030-over if desired.

The 307 heads allow using a 307 factory four-barrel intake manifold or an Edelbrock Performer Olds 350 intake (PN 2711, non-EGR; PN 3711, with EGR). Then you can use the four-barrel carb of your choice: a Quadrajet with the factory intake, a Quadrajet or a small Holley with the 3711, or a Quadrajet, small Holley, Carter AFB, Edelbrock Performer or Edelbrock Thunder AVS carb with the 2711.

Don’t go nuts in the cam department on this small-cubic-inch engine. What’s usually considered a mild cam in a larger 350 engine will act like a big cam in the little 260. Besides, there’s that potential valve-to-cylinder clearance issue. I wouldn’t go any bigger than a Mondello (or equivalent) JM-18-20 flat-tappet hydraulic (0.488/0.496-inch lift, 216/226-degrees duration at 0.050, 260/266-degrees advertised duration, 112-degree lobe-separation angle).

Small-ci engines need to wind up higher to make power, so you may need steeper gears out back as well—especially back in the late ’70s before overdrive transmissions, the factory put in really mild gears to meet emissions and improve mileage.

At least for the 5A 307 heads, there are plenty of common factory four-barrel intakes that fit, including factory Q-jet intakes or an Edelbrock Performer Olds 350—PN 2711 for non-EGR use or (shown) PN 3711 for EGR applications.

At least for the 5A 307 heads, there are plenty of common factory four-barrel intakes that fit, including factory Q-jet intakes or an Edelbrock Performer Olds 350—PN 2711 for non-EGR use or (shown) PN 3711 for EGR applications.

As for a good air filter, that’s a universal part, limited only by packaging constraints. Always run the biggest air filter you have room for. Check out K&N Filter’s offerings or (for cold-air induction systems) Air Inlet Systems. For reference, hard-core Olds engine specialists include Dick Miller Racing and Mondello Performance.