Respectively and respectfully referred to as the "Rat" and "Mouse" motors, GM's seminal big and small block V8 engines have been the benchmark for American muscle from practically the day they were made. These engines are among the few holdouts from the muscle car era in the current marketplace. As 2010, GM still builds new small blocks for sale to the aftermarket, and still uses a variation of its original big-block in many truck applications.

Prior to the introduction of its original small-block in 1955, Chevrolet's hottest sports car engine was the Blue Flame straight six used in Corvettes. When Ford's V8-equipped Thunderbird began outselling the Corvette at an ego crushing rate of 23-to-1, Chevy fired back with its now legendary 265 small-block. Using the basic architecture of the small-block, Chevy up-sized the design in 1958 to create its first ever large-car-and-truck big-block. Although those first displacements were well within small-block territory (348 cubic inches), the big-block would soon grow to 409 cubic inches (1961), followed by the second generation's 454 (1970) and the modern big-block's massive 502 cubic inches.

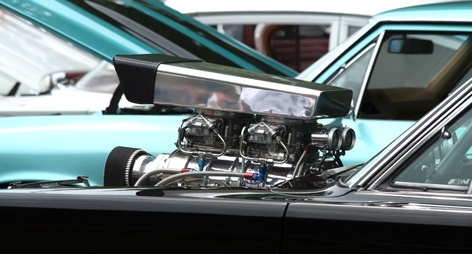

An engine's power potential is ultimately determined by how much air can flow through the cylinder heads. Some heavily modified small-block race heads can easily eclipse the airflow of stock big-block heads, but the small blocks remain at an inherent disadvantage when it comes to size. Supercharging and turbocharging can easily offset the big-block's larger intake and exhaust runners, but (all else being equal), the same amount of boost in a big-block engine will yield far more power than a small-block engine of the same displacement.

Small-block Chevy engines feature excellent horsepower-to-cost ratio. Chevy made millions of small blocks and used them as standard equipment in dozens of full-sized cars and trucks. Big blocks have always been optional equipment on all but a few vehicles, which makes them rare. Walk into any junkyard in the country and you're likely to find 10 good Mice for every running Rat. The laws of supply and demand dictate that the rarer of the two will be more expensive.

Cost-to-benefit ratio starts to swing in the big rat's favor when building a naturally aspirated (non turbocharged/supercharged/nitrous) engine. When Chevy High Performance had two engines built on a budget of $6,500, big-block trumped small to the tune of 51 horsepower and 48 pound-feet of torque (594 to 543 horsepower and 622 to 547 foot-pounds, respectively). However, throw a supercharger, turbo or nitrous oxide into the mix and you could easily build a 600 horsepower Mouse for far less than the $6,500 cost of the naturally aspirated big-block.

Aside from cost and lack of availability, the Rat's primary drawback is its sheer size and weight. In stock form, a 454 big-block tips the scales at just under 685 pounds compared to the 575 pounds of a standard small-block. You can reduce the weight of either engine by more than 100 pounds by using aluminum heads, intake and tubular headers, but such lightweightbig-block parts can be prohibitively expensive. Aluminum small-block parts are relatively cheap and easily accessible, so Mouse trumps Rat for weight. The big-block is 2 to 4 inches larger than the small-block in length, about 5 inches wider and 6 inches taller.