What does it take to build serious horsepower? If you listen to Tony Bischoff of BES Engines, the winner of the 2007 Engine Challenge, he'll tell you it comes down to getting not making mistakes, and things just coming together "right." What the modest, poker-faced Tony won't tell you-at least not right away-is the way common-sense analysis of what is really going on can pay off, and how to apply those ideas to build a better engine. As the champion of our national engine building competition for two consecutive years, Tony has more than a few tricks up his sleeve, but swears by an engine building philosophy that comes down to applying years of experience in knowing what an engine wants to get the job done.

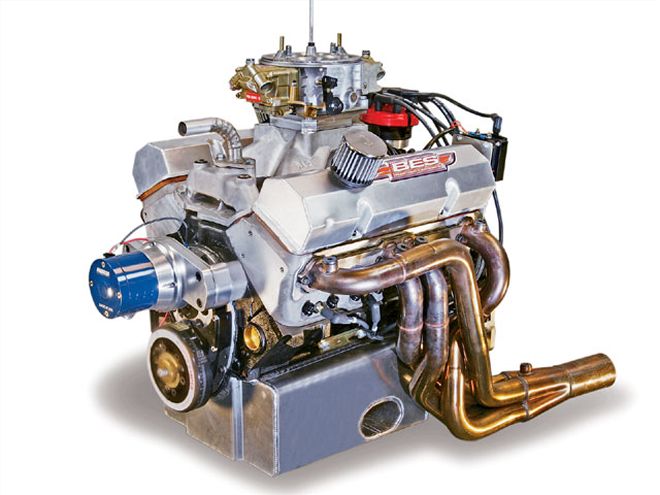

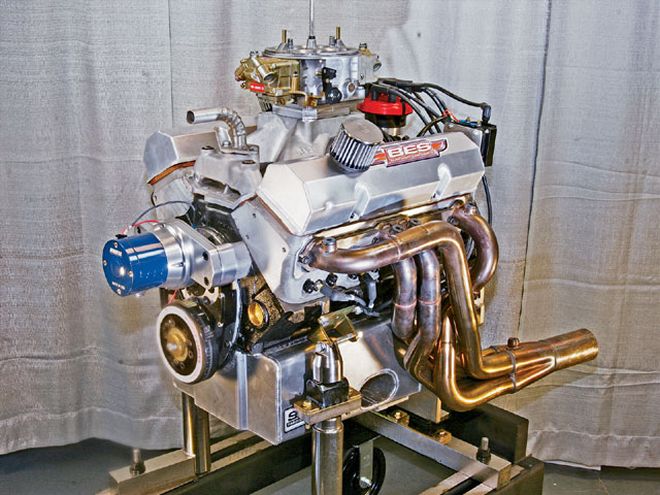

Making big power from a 403-cube engine requires unrestricted airflow, but a broad power curve, including low-end output, is a trickier proposition. Tony's Chevy made use of the ample flow of a Pro-System's 1050 Dominator and BES Racing's tuning to make it work throughout the relevant rpm range.

Making big power from a 403-cube engine requires unrestricted airflow, but a broad power curve, including low-end output, is a trickier proposition. Tony's Chevy made use of the ample flow of a Pro-System's 1050 Dominator and BES Racing's tuning to make it work throughout the relevant rpm range.

The 2007 Engine Masters Challenge was open to any stock bore/stroke-combination domestic V-8 engine above 300 cid. In the prior year's event, the inherent flow advantage of the Ford Cleveland engine seemed indomitable, and Tony lead the pack with the winning Cleveland combination featuring CHI 3V cylinder heads. It surprised many competitors to find that returning champion Tony had selected a smallblock Chevrolet for the 2007 event. With a steep 23-degree valve angle in an inline arrangement, it would seem the Chevrolet would be substantially disadvantaged in comparison to the canted-valve Fords. So why did Tony choose to run a Chevrolet? Tony tells us, "Oddly enough, I wanted to be different...that's kind of odd to say with the Chevrolet, but I was tired of the Fords winning, and I didn't want to spend much money."

While the Chevy may have seemed disadvantaged in this competition, Tony explained to us that this choice does have some very practical advantages. On the notion of the Chevrolet as the underdog, Tony commented, "It was, but it wasn't. The lifter diameter hurts it, they don't have nearly as good of a cylinder head as a cantedvalve head, and I didn't have a good bore and stroke combination; but what it did have is readily available parts, and cheap, light parts. I could get an Eagle crank for $450, and it's relatively light; Eagle rods for $299, and they're light. I could get a brand-new block so that I didn't have to hunt the junkyards trying to clean up six or seven blocks before I get a good one. I could just buy a new block for $1,400. Those were the reasons, really." Here we are seeing some of the same reasons why the Chevy small-block is a favorite of so many regular street guys, namely the tremendous aftermarket support and parts availability. To Tony, just like Chevy fans everywhere, it just made sense to take advantage of the ready and easy parts availability that comes with building a small-block Chevrolet.

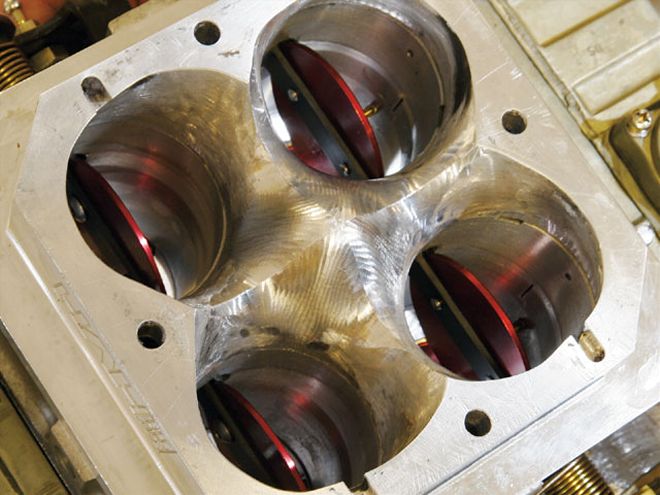

A Dominator's throttle butterflies are spread fairly far apart compared to a 4150 carb, which leads to lots of dead area just under the throttle bores. A tapered HVH spacer helps maintain the velocity through the carb and into the intake manifold.

A Dominator's throttle butterflies are spread fairly far apart compared to a 4150 carb, which leads to lots of dead area just under the throttle bores. A tapered HVH spacer helps maintain the velocity through the carb and into the intake manifold.

In the Engine Masters Challenge, competitors could choose to build a small-block in a stock displacement of their choice, so long as the combination was over the 300-cube minimum. With 302-, 305-, 307-, 327-, 350-, and 400-inch displacements available, why did Tony choose the largest of these possible combinations? This is where Tony's experience came into play. As Tony told us, "This isn't a very scientific study, but I've been dynoing engines for about 10 years, and I keep all our dyno sheets in order of cubic inch, and I just went through all our dyno sheets. Peak torque per cube was the best in about the 400ci range. That was just in my tests. Of course, I don't usually pull the small engines down to really low rpm, so there isn't much data there, but the ones I did pull down low didn't make a lot of low-end torque. Some guys believed that the small engines were the only way to go, and they could be correct, but I decided to go with a 400ci small-block.

The odd-looking plenum entry was simply the result of matching the opening to the resultant shape of the cut-down HVH adapter/ spacer.

The odd-looking plenum entry was simply the result of matching the opening to the resultant shape of the cut-down HVH adapter/ spacer.

Tony further elaborated on his thoughts on this cubic inch choice: "Part of my theory was that most of the cylinder heads are designed close to the same capacity within the range we work in, and really the size of the cylinder heads in the relevant rpm range fit a 400-inch motor better than the smaller engines. Also, the parasitic losses per cube go down a lot as the motor gets bigger, and I thought that could help a little. Every one of the engines has to spin the same amount of parts in them. Even though the bore and stroke are bigger and there is more friction, there's the same friction in the valvetrain, the same friction in the bearings, and so forth. Those are some of the things I was thinking about. We only built one motor, so I took my best stab at it."

One of the items that generated quite a bit of interest in Tony's engine was the cylinder heads. The cylinder heads are from an Australian company called Racer Pro. Tony tells us he was looking for cylinder heads and was discussing the options with John Konstandinou of CHI, who supplied the cylinder heads for Tony's Cleveland engine in the 2006 event. Tony fills us in on how the head choice came about: "John was trying to talk me into running the Cleveland Ford, and he said the foundry that casts his heads cast these 23-degree Chevy cylinder heads. The heads they sent us are normally CNCed, and that kind of bothered me because I don't have a CNC machine, and I had to port them myself."

There was considerable hand work throughout the engine, including the fully ported runners. Tony shapes the runners to meet his ideas on the required runner cross-sectional area and taper.

There was considerable hand work throughout the engine, including the fully ported runners. Tony shapes the runners to meet his ideas on the required runner cross-sectional area and taper.

Tony filled us in on the details: "I wanted the ports to be relatively small, so I was shooting for something around the 230cc range. There was nothing too fancy about the head, but when I was done, it flowed really well for me. We got it up to about 340 cfm on the intake; I mean, it's nothing crazy, but it's not too bad for what we were doing. The head had really good midlift, though at anything after .600-inch it just stalled really hard. Part of that was because I kept part of the port really small. The exhaust flowed about 230 cfm. Technically, the head is a raised port, but it's made in a way that the stock intake bolts right on." The valves measured 2.19-inch on the intake and 1.60-inch on the exhaust.

Tony selected a beehive spring with a 270 lb/in rate because he was looking for a low spring load, and the beehive allows good control with less spring loading. This is an important consideration with the competition's flat-tappet requirement. Adding some insurance against wiping a flattappet lobe, Tony used Ferrea lifters, which are a very hard, lightweight, tool-steel lifter with an EDM oil feed hole to provide additional lubrication at the lobe. Other tricks in the valvetrain include hollow-stem valves, which reduce weight for better control with less spring rate, and Jesel's offset shaftmount rocker arms.

More custom work shows in the intake's cutaway valley plate. Tony believes in the benefit of keeping the intake manifold running as cool as possible, and a separate valley plate helps isolate the intake from engine heat.

More custom work shows in the intake's cutaway valley plate. Tony believes in the benefit of keeping the intake manifold running as cool as possible, and a separate valley plate helps isolate the intake from engine heat.

While carving the heads was a big project in itself, it was also clear that Tony had a high level of development in the intake manifold. Tony explains the details: "There was quite bit of work in the intake. We extended the dividers a little bit, and that helps the low-end score a little. That epoxy in the bottom, I'm not sure if that did anything; I extended the intake runners and epoxyed at the same time, so I don't know, but it picked up a couple of numbers for us. We ran a Dominator, and with the 1 1/4-inch spacer rule, we took a two-inch HVH adapter spacer and milled the bottom off it and put a bolt pattern on it. That's how the spacer ended up with that shape, and we just matched the manifold to it."

Looking at the bottom end, the block was a new casting from World Products, which was bushed in the lifter bores by BES Racing. This may not have been necessary, but Tony is well aware how critical the lifter alignment becomes with very aggressive flat-tappet camshafts, and he felt more secure in locating the bores by bushing them himself. The rods are 5.7-inch Eagle pieces, though Tony was not certain if that selection was the optimal choice. Tony said, "I think if I had a roller cam with the short rod it would have made better mid- and low-range numbers, but with the flat tappet, [the cam rate-oflift] is so much slower in the middle that I think a little slower piston speed, and a little more dwell, would have helped with the flat tappet. That's one thing I'd like to try, just leave the motor all the same and put a longer rod in it."

The pistons are from Ross and utilize an off-the-shelf dish profile, while the skirt profile is a heavy-duty design that Tony originally used in his nitrous engines. Tony found this skirt design also seemed to make more power in normally aspirated engines, even though there are certainly lighter pistons available. The ring pack features a Dykes top, a .043-inch second, and a 3mm oil ring. Tony claims he's never used a Dykes before, but he liked the idea of the improved compression sealing with the low friction a Dykes ring offers.

Even if everything else is done perfectly, the final results of an engine combination depend upon the camshaft selection. If the camshaft looks odd, it's because Tony hand-polished the cam, and he claims to have the blisters to prove it. The cam core is COMP's M55, which is a harder-than-standard cast core. Tony's prep was to take some No. 400 emery cloth, roll the cam in a crank polisher, and polish it with thumb pressure. Tony commented, "Whether it helps or not, I don't know, but I was so worried about wiping lobes off... I can tell you this, the lobes turned over way easier when I did this."

Inside the lifter valley, we see the World block was treated to lifter bore bushings by BES Racing. Tony did not make a major point of trying to control windage and drainback, as evidenced by the lack of valley standpipes.

Inside the lifter valley, we see the World block was treated to lifter bore bushings by BES Racing. Tony did not make a major point of trying to control windage and drainback, as evidenced by the lack of valley standpipes.

All of this concern was because Tony was intent on using the most aggressive solid flat tappets he could find in the COMP catalog for the .842-inch lifters, and then punishing those lobes with a very high rocker ratio. Here, the Mopars and Fords have an advantage over the Chevrolets, since the larger .904- and .875-inch (respectively) lifters allow for faster-acting lobes and more lift for a given duration. Tony's selection was a pair of COMP's MH-series lobes, No. 6280 on the intake and No. 6284 on the exhaust, giving a duration specification of 252/258 degrees at .050 tappet rise. Combined with the 1.9/1.8:1 Jesel rocker combination, .697/.670-inch valve lift was achieved. The cam was ground on a tight 106-degree lobe separation, and Tony found optimal average power at an installed centerline of 98 degrees.

Overall, attention to detail and common-sense engine building are the hallmarks of Tony's style. Many at the Engine Masters Challenge were convinced there was nothing that could compete with the Cleveland Ford engines, especially not an ordinary 23-degree small-block Chevy. We think part of the reason Tony went with the Chevy was to prove a point, and the engine just performed. We didn't see any secret magic that made this engine stand above the others, just the basics of experienced engine building played out at their finest.

BY THE NUMBERS BES 403CI SMALL-BLOCK CHEVY Bore: 4.125-inch Stroke: 3.763-inch Displacement: 403 cubic inches Compression ratio: 10.4:1 Camshaft: COMP solid flat tappet Cam duration: 252/258 degrees at .050-inch tappet rise Cam lobe lift: .367/.372-inch Rocker ratio: Jesel offset 1.9:1 intake; 1.8:1 exhaust Lobe separation: 106 degrees Installed centerline: 98 degrees Top ring: custom-machined 1/16-inch Speed-Pro Dykes Top ring gap: .016-inch Second ring: .043 SpeedPro Second ring gap: .020-inch Oil ring: 3mm Piston: Ross dished top Block: World Motown iron Crankshaft: {{{Eagle}}} forged Rods: Eagle 5.7-inch H-beam Main journal: 2.620-inch Main bearing clearance: .002-inch Rod Journal: 2.070-inch Rod bearing clearance: .002-inch Cylinder head: Racer Pro Peak intake flow: 345 cfm Intake valve diameter: 2.190-inch Exhaust valve diameter: 1.{{{600}}}-inch Intake manifold: Dart Carburetor: Holley Pro System 1050 Dominator Header: Kooks 1 3/4 to 1 7/8 step; 3-inch collector Ignition: ICE Damper: ATI Water pump: Moroso {{{DTS}}} DYNO DATA BEST QUALIFYING PULL RPM TQ HP 2,500 474 226 2,600 477 236 2,700 481 247 2,800 489 261 2,{{{900}}} 493 272 3,000 495 283 3,{{{100}}} 495 292 3,{{{200}}} 496 302 3,{{{300}}} 494 311 3,400 490 317 3,500 485 {{{323}}} 3,600 484 332 3,700 489 344 3,800 494 357 3,900 498 370 4,000 504 384 4,100 510 398 4,200 518 414 4,300 527 431 4,400 535 448 4,500 545 467 4,600 555 486 4,700 565 {{{505}}} 4,800 573 523 4,900 578 539 5,000 580 552 5,100 581 564 5,200 578 573 5,300 578 584 5,400 579 595 5,500 578 605 5,600 578 616 5,700 577 {{{626}}} 5,800 575 635 5,900 570 640 6,000 565 645 6,100 561 651 6,200 558 658 6,300 553 663 6,400 548 668 6,500 544 673