The bolt-on combo-we've all seen it, but what's it worth in the real world? Building horsepower for the dyno environment is one thing, and certainly it has merit in terms of raw power, but what do those numbers mean when the engine is in your car and pushing that performance through spinning components? We decided to answer that question via a dyno blast that would result in a pass-or-fail grade. We proposed to Carlisle Productions that we would bring in the hardware and personnel to acid-test a reader's Mopar. Steve Pilic's mobile Dynotek Dynojet chassis dyno would be there to grade our effort. The idea was simple: select a willing reader's ride and perform the mods right there at the show, complete with a before-and-after dyno test. This sounds easy, but in the publishing world, this kind of live (non-foolproof) project could be akin to suicide. Too many variables, not enough time, no room for errors, and most importantly, no way to cover your rear. Of course, we decided to do it anyhow.

We used Dale Mathews' '71 383 Road Runner, a nicely detailed street resto with a rebuilt resto-stock 383. Since Dale isn't a drag racer, the engine had been rebuilt with stock-level replacement parts. We only required that the engine pass a cranking compression test to make sure we were dealing with eight good holes. We knew a 440 would have more potential for the upside due to the increased displacement, but the 383 fit our criteria of making these changes to a typical musclecar engine. By the way, Dale doesn't own a trailer; he drove the car from North Carolina and planned to drive it home once we were finished.

The Combo

We were after a hot street combo. Dale indicated the engine was rebuilt with forged replacement SpeedPro pistons, so we figured the short-block was easily reliable to 6,000 rpm. We asked where the pistons ended up at top dead center, and Dale thought the piston deck height was .012-inch down. He agreed to pull out the MP cam-the only internal improvement from stock-and replace it with a bone-stock unit and swap the Holley carburetor for a stock AVS. The Road Runner is equipped with an automatic, the stock converter, and 3.23 gears out back; it had to retain its streetability, so we weren't looking to build a full-tilt drag engine. To find serious extra power, we wanted to science-out airflow and spark: the heads, intake, carb, cam, valvetrain, ignition, headers, and exhaust.

We saw what the new Edelbrock heads could do on the engine dyno (see the Oct. '01 issue) and were impressed. Out of the box, they'll make more power than the stockers, even on a relatively mild combo. Theoretically, at 210cc, the port size won't give away any torque generation at the low end. Previous testing on the engine dyno with a 440 confirmed this, and the Edelbrock heads actually showed more bottom-end torque than the stock heads. At the top end, the head's 291-cfm peak intake flow (Edelbrock's number) significantly outperformed the 383's stock 346 castings; the ports are quite efficient, making them an ideal replacement for the 383. Better yet, we knew from experience they would bolt right on and fit, a critical requirement for this type of weekend jam session. These heads are a closed-chamber design, with chambers coming in at 84cc, slightly smaller than the stock heads' 88cc. Based on the short-block specs we were given, we calculated the 383's compression ratio would come up to 9.22:1 with the replacement heads.

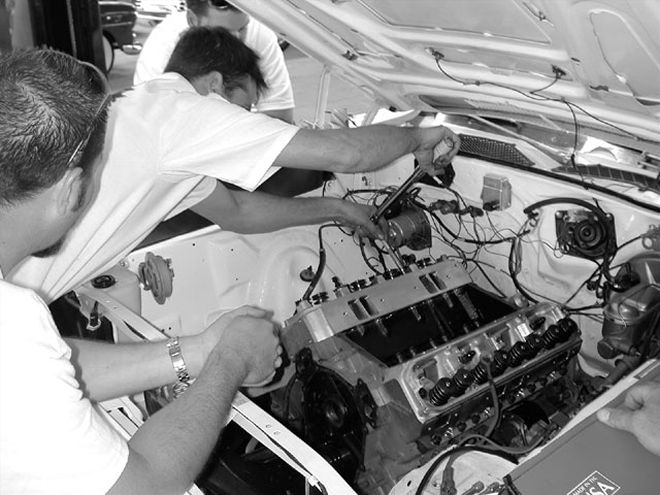

The Edelbrock heads offer excellent power potential out of the box. Since they need hardened washers, we bolted them on with a set of ARP bolts.

The Edelbrock heads offer excellent power potential out of the box. Since they need hardened washers, we bolted them on with a set of ARP bolts.

The intake choice was also clear. On previous engine dyno tests, the Edelbrock Performer RPM two-plane made as much top-end power into the 6,000 rpm range as a high-performance, single-plane intake, while still delivering a good 20-plus lbs.-ft. more torque in the low and midrange. Since we weren't looking to twist the 383 any tighter than that, the RPM manifold received the nod. With this 383/auto street combo, we wouldn't give away any low-end torque if we didn't have to. Though the Performer RPM's 5.8-inch height is quite a bit taller than the stock intake, we figured it would fit under the stock hood of the Road Runner with the low-deck 383 with no problem.

To top the manifold, a Speed Demon 750-cfm carb made the parts list. The 750 size has been the hot-rodders' favorite carb for years, with good reason. It would give us plenty of carb to turn a good number up top, while retaining a venturi size resulting in good response lower in the power curve. At Carlisle, we'd be at a disadvantage as far as carb calibration is concerned, since there's no instrumentation on the chassis dyno to check the carb jetting. It would come down to bolting it on and running it. Past experience on the engine dyno taught us that the Demon carbs turn in the power numbers and are close on jetting as delivered for a typical performance engine. So we had to put our faith in factory calibration, and given our past experience with the Demon carbs, we weren't worried. A vacuum secondary carb was the clear choice, but we also wanted to see if a mechanical secondary would show a performance edge. Carb swaps are simple enough, so we brought along both.

The heart of the matter was the camshaft selection, because we would set the rpm and power potential of the engine through it. With the high-flowing Edelbrock heads, more cam means higher peak power and rpm, even as cam size goes beyond the range of daily drivable grinds. We wanted peak power no higher than 6,000 rpm, and with the Edelbrocks, it wouldn't take a huge duration to achieve that. The main limitations were driveability and valve-to-piston clearance (the Speed-Pro pistons were OE replacement types, without valve reliefs). With the estimated .012-inch deck clearance and no-notch pistons, clearance was a definite consideration. We needed the to maximize power while keeping the combo streetable enough to pull the power brakes, peak near 6,000 rpm, and fit within the confines of the stock-piston short-block. Given the rpm range and the street application, a hydraulic flat tappet was the most sensible choice.

We selected Competition Cams' Xtreme Energy 274H cam. It spec'ed out at 230/236 duration at .050 inch with .488 inch/.491-inch lift on a 110-degree lobe spread and was more than healthy enough to perform the job. In fact, on a 440 with good heads, we'd seen more than 500 flywheel horsepower on the engine dyno with this cam, and the .050-inch duration numbers were quite stout given the cam's moderate 274/286 advertised (seat) duration. The Xtreme Energy cam is quick off the seat, which translates to a more low-end torque for a given level of top-end performance. We also knew this cam was about as large as we could go with the 383's no-notch pistons without risking contact, and about as stiff as we could go with the engine's calculated 9.22:1 compression. A set of Comp's premium No. 867-16 antipump-up lifters were also ordered to ride on the cam.

With the exhaust completed, we could reassemble rest of the 383. First was the Comp XE274H cam. At 230/236 it's a stout stick to be sure, but streetable enough, and a big gain compared to the stock Magnum grind.

With the exhaust completed, we could reassemble rest of the 383. First was the Comp XE274H cam. At 230/236 it's a stout stick to be sure, but streetable enough, and a big gain compared to the stock Magnum grind.

Next, to complement the cam and to set the preload with antipump-up lifters, we went with Comp's No. 1321 Pro Magnum rocker-arm kit. This is a complete kit including shafts and nearly indestructible stainless steel adjustable roller-tipped rockers. They come in a 1.5:1 ratio, which was all we needed with our lift-limited, flat-piston short-block. With the No. 1321 rockers, special-length pushrods are required for proper oiling, so they're best measured while on the engine. The length is right when the oil band in the rocker's adjusting screw is centered in the rocker body's threads with the lash/preload adjusted. This allows oil to flow to the pushrod tip. We didn't have the engine on a stand to measure up, so we calculated the length based on a 440 we previously used these rockers on and subtracted the difference in deck height. A set of Comp 7730-16 pushrods-a 5/16-inch pushrod in a 8.375-inch length-was ordered, and luckily, they fit. We specified premium Fel-Pro gaskets throughout.

The exhaust system was last. Installing headers at a show wasn't outside the realm of possibility, though with some pipes we would think twice. Headers and a full exhaust system? To pull that off, we'd consider only one company, Tube Technologies Incorporated (tti). They make bolt-on exhaust systems and premium-quality headers for Mopar applications, and tti's 1 7/8-inch headers were exactly what the motor needed. We tried several brands of headers with the Edelbrock heads' angled plugs, but they wouldn't fit; we've run both the tti 1 7/8-inch and 2-inch headers with these heads and the fit is perfect. Moreover, we could send Dale and his regularly driven Plymouth down the road with headers and exhaust components that tuck up close to the chassis, as opposed to the pavement scraping design of other products.

We talked to the boss at tti, Sam Davis, to see if tti would stick their necks out for a live install with us. He only asked whether we'd like to use the 2 1/2- or 3-inch system. That's confidence in your product. Sam advised that 450 flywheel horsepower is the point that the 3-inch system would be most appropriate. We didn't expect that kind of power from this 383, but decided to roll out the 3-inch system anyway, along with Walker DynoMax mufflers. The Road Runner was a column-shift, and normally, the column-shift linkage interferes with the header collector, but tti makes a linkage bellcrank assembly to clear. The icing on the cake was tti's recently introduced repop slotted "machine gun" tips for '71-and-up B-Bodies. Unlike the factory piece that bottlenecks inside to a mere 2 1/4 inches, the tti version holds the stock outside diameter and appearance while utilizing a full 3-inch inner pipe. Very nice. Knowing the extent of the work ahead, Sam sent his son Mike Davis and tti tech man Mike Shirley to Carlisle to handle the exhaust part of our mods.

A new set of ignition wires was the final detail. The stock wires were routed for manifolds; with the header install, the wires would need to be custom-cut and routed and would need angles at the plug end from straight to 90 degrees. We like the MSD 8.5mm SuperConductor wires, so we ordered a cut-and-crimp set (PN 31199). These MSD wires come with multi-angle plug ends that will bend the boots to any angle for a clean installation. This job was made easy with MSD's wire crimpers (PN 3505), a great tool for this type of work. From experience, we also knew the MSD wires last better when the going gets hot.

We went with a Demon carb, selecting the Speed Demon 750 in both the mechanical and vacuum secondary configurations. Demon doesn't have a Mopar linkage adapter, so we reworked a Holley bracket. With some quick cobbling, it worked.

We went with a Demon carb, selecting the Speed Demon 750 in both the mechanical and vacuum secondary configurations. Demon doesn't have a Mopar linkage adapter, so we reworked a Holley bracket. With some quick cobbling, it worked.

The parts selection was decided. We calculated that a 383 with this combination would be good for about 435 flywheel horsepower. That number wasn't generated by a whiz-bang computer program or pulled out of a hat. We did the math by interpolating the combo in relation to real-world experience with other Mopar big-block engines we've run on the engine dyno, and 435 flywheel horsepower is stout for a street 383. According to Steve Pilic, a former Detroit powertrain engineer and operator of the mobile Dynotek Dynojet chassis dyno, a TorqueFlite street car shows 75 percent of its flywheel engine-dyno number at the rear wheels. Some of this loss is through the drivetrain, and some has to do with the different correction factors relating to engine dyno versus chassis dyno. Given our ideal flywheel-power projection, we could figure that we'd have 325 rear-wheel horses if everything was perfect. In real life, on some guy's 383, we'd be happy to see more than 300, and we weren't going to make any predictions.

The Baseline

Friday morning we met Dale at the fairgrounds, and he rolled his Road Runner over to meet the Dynojet. He was understandably nervous, wondering what his dead-stock 383 would put out. In a few minutes we had the baseline numbers, showing a disappointing best of 158 hp at 5,400 rpm at the rear wheels after three pulls. Dale was a bit shaken by the results, and this was admittedly weak for a 383 Magnum, but the car pulled clean through the test without sputtering or missing. Based on the factory-rated 250hp SAE net rating for the '71 383 Magnum, the rear-wheel output should have been 187.5 hp. The SAE net numbers were for the engine as installed in the car, breathing through the stock air cleaner and exhaust, with all the accessories, as the car was tested.

We weren't happy with this baseline, and the unrebuilt AVS carb was the first suspect. In fact, on coastdown from the final dyno pull, the high vacuum created as the heavy rollers spooled down pulled a lot of fuel from the carb and fouled the plugs. We bolted on a new AFB, but the completely wet plugs made any further testing useless (getting it started proved futile for the moment as well). For what it was worth, we now had the baseline numbers on the car, and we flat-towed it back to our work area.

We custom-cut and fit a set of MSD's excellent 8.5mm SuperConductor wires. The MSD tool makes factory-looking end crimps a snap. It's expensive, but worth every cent for this job.

We custom-cut and fit a set of MSD's excellent 8.5mm SuperConductor wires. The MSD tool makes factory-looking end crimps a snap. It's expensive, but worth every cent for this job.

Spinnin' Wrenches

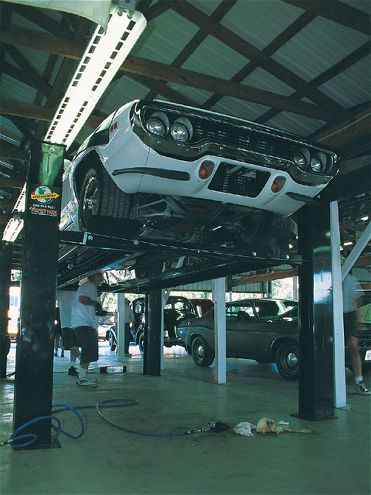

At 10:55 a.m. Friday, our plan was to swap the heads, intake, carb, cam, lifters, valvetrain, and exhaust system; cut a new set of ignition wires; and have the car turn-key by the next day. Bill Gray from Lifts Unlimited set up a four-post lift (Perfect Park 7000) in our work bay in Pavilion B at the fairgrounds. Tool distributors Carl and Ken Wetzel parked their fully stocked MAC Tools truck just outside, so it was time to get busy. First we stripped the exhaust system, which the Mike and Mike crew performed quickly. Here's a timeline:

11:22 a.m.: Using the Perfect Park lift, the old exhaust system from the manifolds to the tail was on the ground.

12:23 a.m.: The 383 was stripped to the bare short-block, and the parts and surfaces were cleaned to prepare for reassembly. With the block unencumbered by the heads, we had a look at what we would be working with. The bores looked good, as expected for a fresh engine. Next, we spun around the crank to check the piston deck height. Surprise! The pistons were nowhere near the .012-inch deck we'd based our combination on. We didn't bother to measure it, but the pistons were at least .080-inch down the hole at TDC. We never got to the bottom of it; the slugs were low.

Publisher Jerry Pitt was understandably nervous when we broke the news. "Jerry, it doesn't have any compression [ratio]."

"Are we dead?" he asked.

After hitting the streets for a shakedown run, we had to run it on the dyno. Dyno operator Steve Pilic cut the testing short due to a bad driveline vibration, but we reached 301 horses at only 5,100 rpm.

After hitting the streets for a shakedown run, we had to run it on the dyno. Dyno operator Steve Pilic cut the testing short due to a bad driveline vibration, but we reached 301 horses at only 5,100 rpm.

Well, not necessarily dead. We just didn't have a 9.2:1 ratio 383, but rather an 8.5:1 short-block, and it was going to hurt. The extra clearance volume would make the engine lope more at idle, and the lower ratio would soften the bottom end by maybe 25 lbs.-ft. Once it was spinning, though, airflow would take over, and it should make some power. In fact, if you told us to put together the best combo for a low-compression 383, the parts list wouldn't change much. This combo was ideal on pump premium at 10:1-plus compression, but we had to work with what we were dealt.

1:30 p.m.: We lost 45 minutes rounding up some head gaskets, since the ones we ordered hadn't arrived at the fairgrounds yet. Luckily, the guys at Mancini Racing were set up on the Manufacturers' Midway and came through with the goods. The Edelbrock heads went on, sealed with premium Fel-Pro wire ring gaskets. To substitute thinner steel shim gaskets for the Fel-Pro piece would have made up some ground, raising the ratio about 4/10 of a point. However, under the gun and with no second chances, it wasn't worth the risk. The Fel-Pros were sure to seal as tight as a drum, and we couldn't afford to risk a leak. The heads were secured with a fresh set of ARP bolts, since aluminum heads require hardened washers under the bolt heads.

1:48 p.m.: The last head bolt was torqued, and the Mikes from tti were clear to install the headers and exhaust.

4:00 p.m.: Mike Davis and Mike Shirley from tti bolted in the 1 7/8-inch headers without even raising the motor. They fit the Edelbrock heads and B-Body chassis like a glove.

7:00 p.m.: We worked with clamps and human strength, and the full 3-inch exhaust system was in place, right down to tti's gorgeous slotted tips. It was time to get back to the engine.

7:15 p.m.: The Comp XE 274H cam and Comp lifters went into the engine.

9:15 p.m.: Comp pushrods and rockers were installed and lashed to .006-inch preload (1/8 turn from "0" lash).

9:20 p.m.: The Performer RPM intake was installed. Dale bought a set of new cast-aluminum MP valve covers from Mancini (who saw us a lot), but the flash chroming on the bolts had increased their size slightly. We didn't want to risk stripping the heads out; after the first one seized up going into the virgin aluminum, we instead got a set of proper-sized replacements at the hardware store (the stock bolts wouldn't work due to the increased lip height of the aluminum covers).

10:00 p.m.: The throttle and kickdown linkage were done. The stock linkage bracket needed mods to clear the higher runners. Bending and grinding the bracket made it functional, but this cost us time.

10:35 p.m.: We installed the timing cover, damper, front accessories, fuel pump, brackets, belts, and pulleys. The people from Carlisle told us a local news camera crew was coming over to film us, so we looked busy.

11:40 p.m.: Upon examination before stabbing and timing the distributor, we discovered that the 1971 original showed serious bushing wear and contact between the reluctor and pickup unit. We also found the intermediate shaft (distributor drive) badly scored. We went back to Mancini, who had the MP ignition set we needed as well as the heavy-duty intermediate shaft (this after we got them out of their camper parked nearby). Once in place, we cut a fresh set of MSD 8.5 SuperConductor wires.

12:35 a.m.: The radiator was in, and we hooked up the engine wiring harness and sewed up the little details.

1:05 a.m.: That's a wrap, gentlemen. Time for a cool refreshment. We still had a few minor details to attend to the next day, such as getting a new tranny-cooler fitting to replace the stripped one in the radiator, and hitting the auto parts store for a fresh piece of fuel hose. Fourteen hours had elapsed from start to finish, including lost time locating parts and making linkage modifications.

This combo worked to wake up the potential of the 383, and here is Dale with his family and the crowd during the final pull.

This combo worked to wake up the potential of the 383, and here is Dale with his family and the crowd during the final pull.

It's Alive

The next morning, with all the nuts and bolts back in their proper places, we dialed in 12 degrees of initial timing at the damper, set the pickup in line with the reluctor, and dialed in the new MP electronic distributor to No. 1. Once the bowls of the Demon carb were primed, we prepared to fire up the beast. It lit on the first revolution of the crank, and we set the idle speed to 2,000 rpm for the cam run-in. Man, it sounded healthy. After about 15 minutes, we let it settle to an idle before tweaking the Demon's four-corner idle screws to smooth the chop and setting the distributor for 38 degrees total advance. The low ratio gave it a little more lope, while a stab of the throttle produced a clean roar of power. If it only needed to sound tough, with the tti system and the Comp cam, we could have packed up and gone home. To say Dale was happy would be an understatement; you couldn't have beat the smile off his face. Our official "after" test was scheduled for Sunday, but we wanted to see if the Road Runner now had the bite to match its bark.

Dale nodded his OK, so Mike and Mike and I took the Road Runner out for a shakedown street run. We worked the column in slap-stick fashion and shifted by ear (no tach), and the white Plymouth got up and moved; this thing was cranking. We put the mechanical secondary carb on the car to get the most out of the romp, but it was a bit too much for the low-compression engine at low rpm. Once moving, however, it came on like a freight train and wound out nicely. Some tuning might have helped the throttle response with the mechanical secondary, but we figured the vacuum secondary would be the way to go with the stock converter in the automatic and tall highway gears. Regardless, we had some horsepower on tap. We pulled back into the fairgrounds and headed for the dyno.

Sneak Peek

Though it was only Saturday, we wanted some numbers to back up our gut reaction. We estimated the potential of the 383 at 325 rear-wheel horsepower with this combo of parts, but that was with 3/4 of a point more compression. Even with the lower ratio, it felt good-good enough to break 300. Steve Pilic wheeled it up the ramp to the Dynojet.

Steve fired the 383, dropped it into gear, and it settled into a low lope. Then he brought it up through the gears and dropped the hammer. The mill sounded crisp as it loaded against the rollers, but at 4,500 rpm Steve backed out. The dyno's tach showed 285 hp and well on its way up.

"It's getting hairy at higher rpm; got a bad shake," Steve reported from the driver's seat.

"They all do; don't worry about it ... wind it up to six grand," we recklessly urged.

Steve wasn't convinced, but agreed to give it a try. This time we watched the tach on the dyno's display and were surprised when again Steve backed out early-this time at a solid 301 hp at 5,100 rpm.

"What's up? That's only 5,100. It's not done," we protested.

"Maybe it's not," Steve replied grimly, "but I am."

We saw he was serious and figured something must be amiss with the 'Runner. Still, we crossed the magic 300 rear-wheel level, and we had at least another 700 rpm to go. We changed to the vacuum secondary carb and took it out for another shakedown run on the backroads of Carlisle. Last time out, we banged it through the gears and she rocketed smooth as glass. This time, by the middle of First, or about 40 mph, it had a serious driveline vibration. At 5,100 rpm in Third, Steve was spinning it to at an actualized road speed of 118 mph; at that speed, the driveline must have felt like it was about to come right through the floor. Sorry, Steve. On the bright side, we found the vacuum secondary carb pulled clean at low rpm, giving excellent throttle response.

We limped back to our pavillion workspace and raised the Road Runner on the lift. Neither U-joint clip at the pinion yoke were in their grooves. At the front U-joint, we found two cups mismatched and machined for wider clips than installed. It was late and our tool truck was gone, but Dale produced a 3/8-inch wrench to pull the 'shaft. Once again Mancini Racing rescued us with two new U-joints and a transmission yoke to replace our suspect-looking one. We had a hammer, a block of wood, and a screwdriver. That's all it took. The driveshaft was rebuilt and back in place 45 minutes later. A quick road test, and again it was as smooth as glass.

Sunday, Sunday, Sunday

We came back to the Dynojet for our "official" test early Sunday afternoon. Dale's Road Runner had cracked more than 300 hp in our earlier test without even reaching peak horsepower rpm. We used the mechanical secondary carb for this pull, with the vacuum carb standing by on the bench. With the rebuilt driveshaft, Steve hammered it up to 6,000 rpm, and we had a grand total of 311 hp at 5,900 rpm. Next, we switched to the 750 Speed Demon vacuum secondary carb, and it turned in 309 hp at 5,800 rpm. Not much penalty there, and better street driveability. Using the dyno operator's conversion, Steve figured the 383's rear- wheel output in the Road Runner equated to 414 hp at the crank on an engine dyno. The bolt-on package netted us a real 153 hp at the rear wheels, nearly doubling the power this Road Runner had coming in. Moreover, with that 8.5:1 compression ratio, we could do it running on 87 octane juice. With some help from our friends, the Carlisle Dyno Blast was a major success.