Adjust rocker arms frequently—or not at all? Rev to the moon—or stop at the smog layer? These are the eternal questions that have plagued hot rodders trying to decide whether to purchase a mechanical or hydraulic-lifter camshaft. Experience has taught us to expect the valves in a small-block Chevy to float at around 6,500 rpm with any hydraulic-tappet cam. This uncontrolled valve float results when the hydraulic lifters pump up with oil at high engine speeds and hang the valves open at the wrong time. At best, this causes the engine to lose power as the camshaft loses control of the valves; at worst, this causes the valves to crash into the pistons. As far as we’re concerned, spinning serious rpm was strictly solid-lifter race-cam territory. Until now.

A solid mechanical lifter avoids the pitfall of the hydraulic lifter’s internal piston moving out of position at high rpm by doing away with the hydraulic (engine oil) reservoir in the lifter. The problem with solid lifters has been that you have to routinely readjust the rocker arms to maintain valve lash as parts wear—which can be a pain in a tight engine bay—making them better suited to race cars than street cars that see many miles. Comp Cam’s new four-pattern camshaft and corresponding valvetrain components are the best of both worlds: race-car performance with street-car manners.

We fitted a 372-inch Chevy with a four-pattern cam and short-travel lifters from Comp Cams and then topped the short-block with a set of Air Flow Research 195cc Street Eliminator heads and Comp’s dual valvesprings. The engine would’ve revved to Mars had we not wussed out at 7,700 rpm and lifted without a hint of valve float. Seriously. It wasn’t our engine or else we would have revved it even higher.

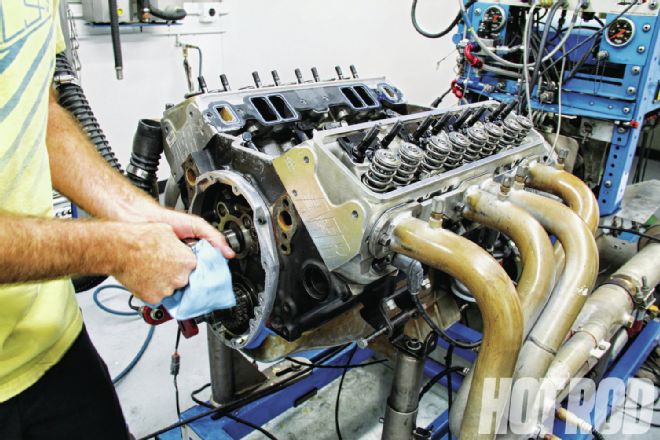

Comp Cams’ two-piece timing cover helped speed up cam swaps by eliminating the need to yank the oil pan off. We still had to pull the intake manifold to access the lifters and the balancer to gain access to the timing set, though. By the third day of testing, we were able to swap cams and have the engine up and running again in less than 40 minutes.

Comp Cams’ two-piece timing cover helped speed up cam swaps by eliminating the need to yank the oil pan off. We still had to pull the intake manifold to access the lifters and the balancer to gain access to the timing set, though. By the third day of testing, we were able to swap cams and have the engine up and running again in less than 40 minutes.

Before you accuse us of expensive valvetrain trickery, you should know the heads didn’t have titanium valves—they had heavier stainless-steel units that are part of AFR’s head package. The heads also used stud-mounted Comp Ultra Magnum Pro Rocker arms rather than the more expensive shaft-mounted variety. The key to the rev-happy nature of this small-block was the new valvetrain components developed on Comp’s SpinTron machine.

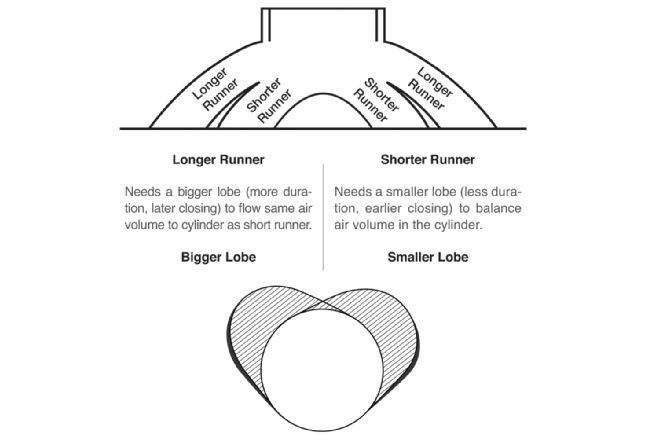

Just what is a four-pattern cam? It’s a departure from traditional single-pattern cams, which feature identical lobe profiles for the intake and exhaust valves, and dual-pattern cams, which feature unique lobe profiles for the intake and exhaust valves. A four-pattern cam uses four distinct lobe profiles; there are two different intake-lobe profiles and two different exhaust-lobe profiles. Using four lobe profiles on a single cam lets the cam designer provide more duration to the four corner cylinders of a V8 (cylinders 1, 2, 7, and 8 on a Chevrolet or Mopar), compared to the four middle cylinders (3,4, 5, and 6). The difference in duration is there to aid cylinder filling, since the longer runners (aimed at the corner cylinders) require more time to fill than shorter ones (middle four cylinders) when fed by a single four-barrel intake manifold.

Pic: Comp Cams

Pic: Comp Cams

The four-pattern cam is nothing new; it’s been used in professional racing ranks such as NASCAR for decades. Although Comp has been marketing it as a solution to the cylinder-to-cylinder distribution problems associated with a single four-barrel intake manifold, there are other features aiding its power production. Comp’s four-pattern stick offers a tighter lobe-separation angle and faster accelerating ramp designs than its Xtreme Energy series of camshafts.

The power increase we found with the new four-pattern cam versus Comp’s bread-and-butter grind, the Xtreme Energy (XE) Series, is not huge, but it is real. We witnessed a 6hp average increase in power and 8-lb-ft average increase in torque with the four-pattern cam. It was also way better down low and offered more ponies at the peaks. Power aside, the increase in operating rpm is the real benefit. We dumped the existing XE cam for the four-pattern cam and gained 1,000 more usable rpm. That means shifting the trans way upstairs and keeping the engine in the fat part of the powerband during shift recovery, which will translate into better acceleration and lower e.t.’s. Best of all, the short-travel hydraulic-roller lifters offer set-it-and-forget-it lash adjustments. Here’s an inside look at a valvetrain that will bring serious heat to any street engine.

The 372 is the dyno mule of Westech Performance Group and has seen upwards of 1,000 pulls on the company’s Superflow engine dyno. It sports a forged rotating assembly with a 3.480-inch Eagle crankshaft and 4.125-inch JE flat-top pistons with a pair of valve reliefs. The Eagle connecting rods measure 5.700 inches long for a 1.637:1 rod/stroke ratio, and the static compression is pump-gas friendly at 10.25:1 when combined with Air Flow Research 195cc Street Eliminator heads’ 65cc combustion chambers and 0.040-inch thick Fel-Pro head gaskets. This is a legit 500hp small-block with most induction packages we’ve tossed on it. We tested two intakes and four camshafts over the course of three days in the dyno cell and went to great lengths to eliminate as many variables in the test protocol as possible, making the small power gains displayed by the Superflow dyno accurate.

All dyno pulls consisted of sweeps from 3,000–7,700 rpm and were made on 100-octane Rockett Brand fuel. A Holley 950-cfm Ultra HP Series carburetor in the company’s new Hard Core Gray finish with black billet metering blocks topped the intake. This 100 percent U.S.-made carb is constructed almost entirely of aluminum and weighs 38 percent less than a traditional 4150 carb with 20 percent more fuel capacity, thanks to all-new, larger float bowls. The list of new features is long. We especially dig the built-in bowl drain ports and the increase in flow from the relocated air bleeds, which are moved outward in the main body. If you’re wondering what the nipples atop the vent tubes are, those are Accufab Racing vent tube fire restrictors, simple check-ball fittings that prevent the fuel in the float bowl from spilling out of the vent tube when the engine is flipped upside-down during an accident.

All dyno pulls consisted of sweeps from 3,000–7,700 rpm and were made on 100-octane Rockett Brand fuel. A Holley 950-cfm Ultra HP Series carburetor in the company’s new Hard Core Gray finish with black billet metering blocks topped the intake. This 100 percent U.S.-made carb is constructed almost entirely of aluminum and weighs 38 percent less than a traditional 4150 carb with 20 percent more fuel capacity, thanks to all-new, larger float bowls. The list of new features is long. We especially dig the built-in bowl drain ports and the increase in flow from the relocated air bleeds, which are moved outward in the main body. If you’re wondering what the nipples atop the vent tubes are, those are Accufab Racing vent tube fire restrictors, simple check-ball fittings that prevent the fuel in the float bowl from spilling out of the vent tube when the engine is flipped upside-down during an accident.

The central location of the plenum in carbureted V8 intake manifolds (designed to fit under the hood of most hot rods) results in less than optimal intake-runner lengths. There simply isn’t room to move the carburetor’s mounting pad high enough to build equal-length runners, such as those found in a modern tunnel ram. According to Edelbrock Chief Engineer Brent McCarthy, the company does everything possible to increase the length of the runners without kinks or bends in the aluminum and considers the plenum volume to be secondary in terms of design. Still, there are significant differences in runner length in the popular single- and dual-plane intakes we tested. It’s just the nature of the beast. Since the four-pattern cam reportedly helps distribution in this application, we quizzed Edelbrock about the differences in runner dimensions and then dyno’d the engine with O2 sensors in each header primary tube to determine if the four-pattern cam made a noticeable difference in air/fuel ratio versus a standard grind. It didn’t in this application.

It was clear that the advantage of the four-pattern cam is in a combination of smoother ramps, increased duration, and a tighter lobe-separation angle—and not just the multiple lobe shapes. Still, we wanted to see if we could quantify the value in the different patterns, so we asked Comp to grind us some special cams. The company responded with a cam that had the inner lobe pattern on every lobe and another cam with the outer pattern on every lobe. We tested those two cams against a legit four-pattern grind, as well as the tried-and-true Xtreme Energy grind.

The Edelbrock RPM Air Gap is a dual-plane intake that makes great power and torque and features a divorced valley floor, which creates a channel between the hot oil in the lifter valley below and the runners and plenum above for a cooler air/fuel charge. It’s designed for 265–400ci engines revving from idle to 6,500 rpm. We found it to have excellent distribution with the standard and four-pattern cam. The only standout was the No. 6 cylinder, which featured the second-shortest intake runner. Cylinder No. 6 ran more than half a ratio richer than the others, no matter which cam was in the engine. Strangely, cylinder No. 4 wasn’t nearly as rich as No. 6, even though it had an even shorter intake runner.

The Edelbrock RPM Air Gap is a dual-plane intake that makes great power and torque and features a divorced valley floor, which creates a channel between the hot oil in the lifter valley below and the runners and plenum above for a cooler air/fuel charge. It’s designed for 265–400ci engines revving from idle to 6,500 rpm. We found it to have excellent distribution with the standard and four-pattern cam. The only standout was the No. 6 cylinder, which featured the second-shortest intake runner. Cylinder No. 6 ran more than half a ratio richer than the others, no matter which cam was in the engine. Strangely, cylinder No. 4 wasn’t nearly as rich as No. 6, even though it had an even shorter intake runner.

RPM Air Gap (P/N 7501) Port No. 1 Port No. 2 Port No. 3 Port No. 4 Port No. 5 Port No. 6 Port No.7 Port No. 8 Runner Length 5.800 5.250 6.000 4.100 5.500 4.250 4.500 5.500 Cross Section 2.210 2.210 2.210 2.210 2.210 2.210 2.210 2.210 Average A/F w/ XE Cam 13.2:1 13.1:1 13.2:1 13.3:1 12.9:1 12.6:1 12.9:1 13.3:1 Average A/F w/Four-Pattern Cam 12.9:1 13.0 12.9:1 13.1:1 12.8:1 12.4:1 13.3:1 13.3:1

*All runner dimensions are provided by Edelbrock and are listed in inches.

The Edelbrock Super Victor II is designed to make power from 4,000–8,000 rpm, and although the runners are shorter than the RPM Air Gap’s, they do feature more cross-sectional area. Again, the four-pattern cam made more power but did little to change the average air/fuel ratio observed throughout the dyno pulls. The Super Victor was worth 13 peak horsepower versus the Air Gap; the Air Gap was better by 25 lb-ft of torque.

The Edelbrock Super Victor II is designed to make power from 4,000–8,000 rpm, and although the runners are shorter than the RPM Air Gap’s, they do feature more cross-sectional area. Again, the four-pattern cam made more power but did little to change the average air/fuel ratio observed throughout the dyno pulls. The Super Victor was worth 13 peak horsepower versus the Air Gap; the Air Gap was better by 25 lb-ft of torque.

RPM Air Gap (P/N 2892) Port No. 1 Port No. 2 Port No. 3 Port No. 4 Port No. 5 Port No. 6 Port No.7 Port No. 8 Runner Length 5.350 5.500 4.650 5.000 5.000 4.650 5.500 5.350 Cross Section 2.850 2.850 2.850 2.850 2.850 2.850 2.850 2.850 Average A/F w/ XE Cam 13.4:1 13.7:1 12.9:1 12.8:1 13.1:1 13.1:1 12.8:1 13.8:1 Average A/F w/ Four- Pattern Cam 13.4:1 13.5:1 12.9:1 12.8:1 13.1:1 13.4:1 12.9:1 13.8:1

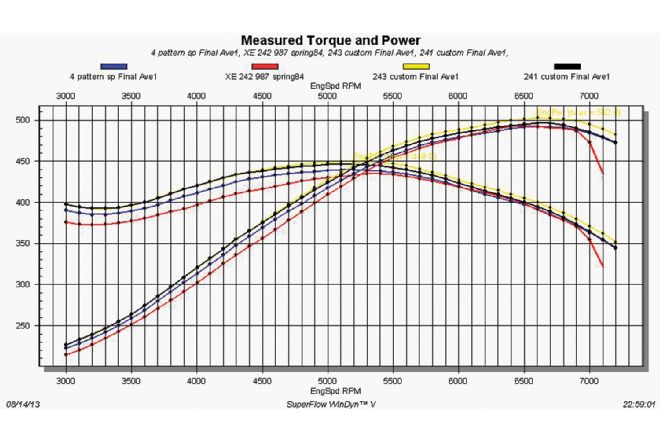

The four-pattern cam (blue line) has two degrees more duration on the outboard intake and exhaust lobes than the inboard lobes. This cam beat the XE (red line) by 7 hp and 9 lb-ft in the 3,000 to 5,000 rpm range but they are even from 5,500 to 6,000 rpm. At 6,500 rpm the XE grind shows a light gain over the four-pattern cam in terms of horsepower but the four-pattern cam is worth 8 more lb-ft of peak torque. When the XE begins its nosedive into valve float at 6,700 rpm (with lightweight Comp 26929 dual springs; with heavier 987 springs valve float occurs at 6,500 rpm), the four-pattern noses over slightly but doesn’t go into valve float, allowing us to keep revving the engine 1,000 rpm higher without damage. The special order cam with the outer pattern on every lobe (black line) on average beat the XE by 9 hp and 13 lb-ft 3,000 to 5,000 rpm, was even with it at 6,000 rpm and down by 6 hp at 6,500 rpm. The cam with just the inner pattern (yellow line) also beat the XE down low from 3,000 to 5,000 rpm, was even

The four-pattern cam (blue line) has two degrees more duration on the outboard intake and exhaust lobes than the inboard lobes. This cam beat the XE (red line) by 7 hp and 9 lb-ft in the 3,000 to 5,000 rpm range but they are even from 5,500 to 6,000 rpm. At 6,500 rpm the XE grind shows a light gain over the four-pattern cam in terms of horsepower but the four-pattern cam is worth 8 more lb-ft of peak torque. When the XE begins its nosedive into valve float at 6,700 rpm (with lightweight Comp 26929 dual springs; with heavier 987 springs valve float occurs at 6,500 rpm), the four-pattern noses over slightly but doesn’t go into valve float, allowing us to keep revving the engine 1,000 rpm higher without damage. The special order cam with the outer pattern on every lobe (black line) on average beat the XE by 9 hp and 13 lb-ft 3,000 to 5,000 rpm, was even with it at 6,000 rpm and down by 6 hp at 6,500 rpm. The cam with just the inner pattern (yellow line) also beat the XE down low from 3,000 to 5,000 rpm, was even

Part No. 12-000-8 Intake Exhaust Gross Valve Lift 0.600 0.619 Duration at 0.050 248 degrees 254 degrees LSA 108 degrees

Part No. 12-000-10 Intake Exhaust Gross Valve Lift 0.638 0.622 Duration at 0.050 243 degrees 253 degrees LSA 108.5 degrees

Part No. 12-000-10 Intake Exhaust Gross Valve Lift 0.637 0.622 Duration at 0.050 241 degrees 251 degrees LSA 107.5 degrees

Part No. 12-474-44 Intake Exhaust Gross Valve Lift 0.638 / 0.637 0.622 / 0.622 Duration at 0.050 243 degrees / 241 degrees 253 degrees / 251 degrees LSA 108.5 degrees / 107.5 degrees